Georeferencing helps take images of maps—like this map of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, or the Sanborn maps featured in this article—and turns them into spatial data that can be read by modern mapping software like Google Maps, ArcGIS, or QGIS. We rely on georeferencing in a lot of our work at the Map Center, with Atlascope using with over one hundred georeferenced atlases of Greater Boston.

Since late 2021, the LMEC has collaborated with Bert Spaan, a map enthusiast and software engineer based in the Netherlands, to support his development of Allmaps, a platform for georeferencing digitized maps. We sat down with Bert to learn all about Allmaps: where it came from, where it’s going, and what’s been most exciting along the way.

Ian Spangler: Tell me a little bit about yourself. How did you find yourself doing this kind of work at the intersection of geography, librarianship, and the digital humanities?

Bert Spaan: Sometime while studying computer science, I discovered I could combine my interest in maps and cartography with my knowledge of programming. As a kid, was always looking at maps and thinking about faraway places. Computer science became a way for me to make maps while using my love of programming and databases, which I turned out to be pretty handy with.

After graduate school, I worked for a company which made GPS and geolocation devices, a web development company, and then a big Dutch GIS company. None of these jobs were perfect, but they taught me a lot that serves as foundations for the work I’ve done since.

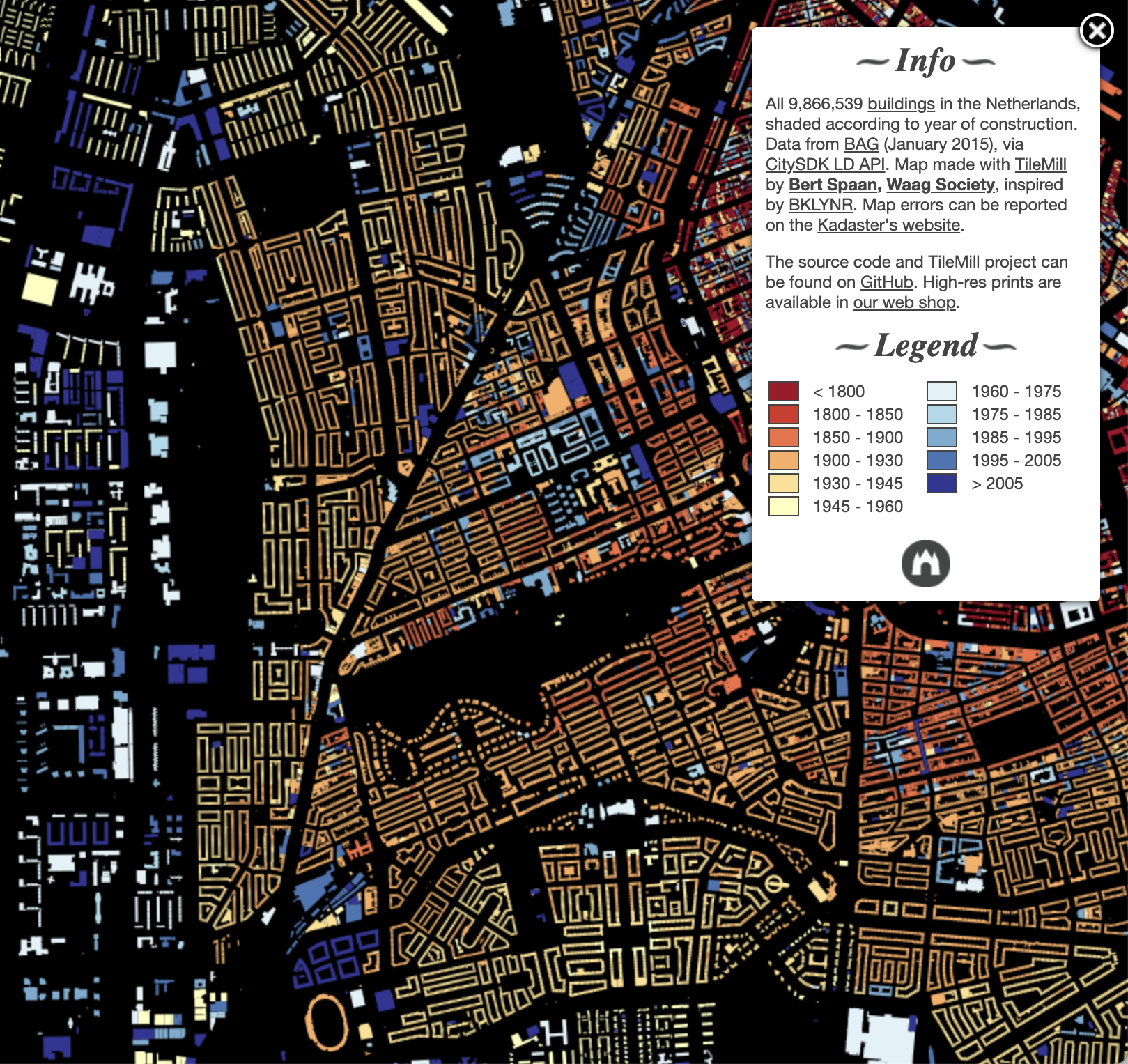

Map of all buildings in the Netherlands, colored by building age

From there, I ended up working at Waag, a Dutch non-profit research institute for arts, science and technology. The projects I worked on mostly focused on open data and software that made accessing open data easier. When I could, I always tried to sneak in some cartography. For one of the projects, I made a map of all buildings in the Netherlands, which led to working on many more cartography projects.

Another project looked at the history of Dutch place names (because Amsterdam wasn’t always referred to as Amsterdam). We ended up turning this into a service called Histograph that was used primarily by historians. It was during this period that I helped organize the Dutch chapter of Maptime, which introduced me to the community of people working across the world in open-source geospatial web development.

I left the Netherlands for New York City to take a job at NYPL Labs—the digital humanities research lab at the New York Public Library—to work in their NYC Space/Time directory, which is a digital atlas of the history of NYC. At the NYPL, I had the chance to work with the Library’s amazing collections of digitized maps and create new tools and websites to make maps easier to find and access, but it only worked for the NYPL and not for other institutions with similar collections. Because of my work at NYPL Labs, I was introduced to the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF), which was created to try and make sharing images and metadata from institutional collections more streamlined. That was ultimately what led me to working on Allmaps with my collaborator Jules Schoonman.

IS: Georeferencing, or the process of associating a pixel of a digital image with coordinates in geographic space, is something we’re really excited about here at the Map Center, given our very large collection of digitized maps. We’ve been so thrilled to partner with you to help migrate our georeferencing workflow into Allmaps. Could you tell us a little bit about what Allmaps is, and explain the major problem that you were trying to solve by developing it?

BS: Allmaps is a collection of software tools that make it easier and more inspiring to explore, georeference and work with collections of digitized maps. I really want there to be an easier way to find, explore, and view digitized maps.

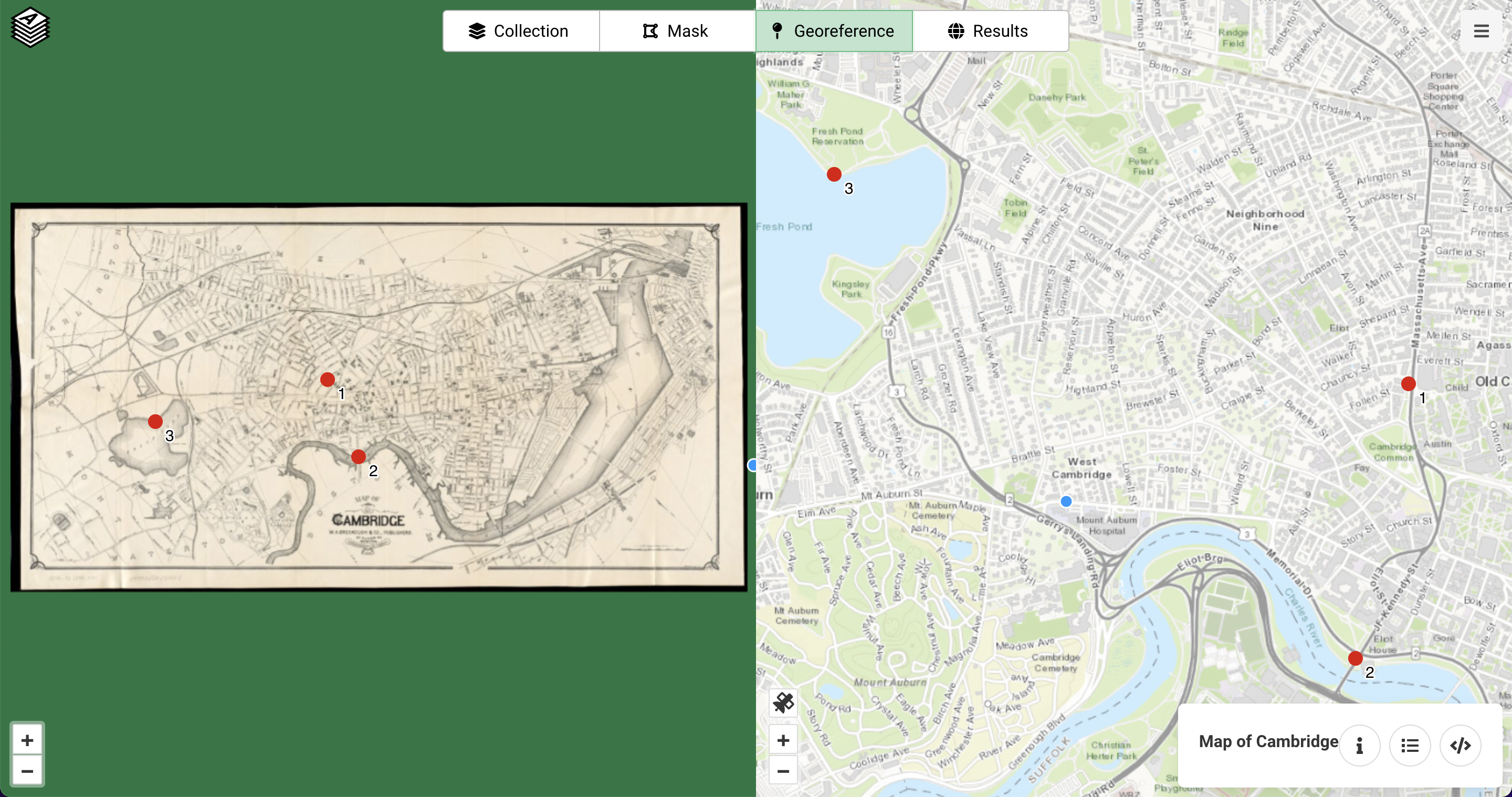

Georeferencing a map of Cambridge in Allmaps

Before I started working on Allmaps, I was doing lots of small projects as a freelancer. I worked with different institutions in the Netherlands that had digitized maps, and I always had to start from scratch because every institution worked in a different way. There was never good software or tools that would make working with collections of maps easier. At NYPL, I made this one tool called Maps by Decade and wanted to replicate it for the Netherlands, but I couldn’t work with Dutch collections in the same manner when I got back.

At that point I heard about IIIF and started thinking about how to make a tool that could help people find maps of one place that might be spread across many collections. I started Allmaps really out of wanting something to exist that didn’t, so I figured I’d just start making it. Many existing georeferencing projects focus on producing GeoTIFFs (image files with geospatial coordinates) or warped maps only, while I’m much more interested in the metadata. By acccessing the metadata, I can display data about the maps in a different way or create an entirely new application using that information, instead of only getting the transformed image files out of the tool.

One of the other things I don’t like about many existing tools is that they’re all about history. There are still beautiful maps being made today, and I think it would be great to show people other modern maps besides Google Maps – it doesn’t need to be Google or historical maps, there are others and I’d love to increase access to them. Allmaps is primarily about the metadata and about open data, so that developers can build on top of it without only having access to the imagery.

IS: I know that the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF) plays a major role in Allmaps’ technical stack—could you talk about what it means and why it’s important to use IIIF and some of the other components that comprise Allmaps?

BS: Before IIIF, every institution used a different technology to access their digitized collections (if it was possible at all). Creating cross-institutional tools that worked with digitized images was very difficult—a lot of the work had to be put into first accessing the images. IIIF makes this part of Allmaps very easy by standardizing how to access images and also standardizing accessing the metadata and creating collections of images.

What I hope is that projects like Allmaps can be a reason for institutions to start a IIIF server. There’s lots of other great examples of tools being built with IIIF, so maybe this project can help inspire increased use of IIIF.

IS: On the user side, what key features distinguish Allmaps from other georeferencers?

BS: With Allmaps, you can start georeferencing any map that’s available through IIIF. There’s no need to create an account or to import images. There’s no need to create derivative images on the server. It all works by using URLs—you can use the Allmaps viewer by using the URL and the same works for the Editor, which makes it really easy to share.

It’s based on open standards and all components of Allmaps communicate by using this open standard, which is the IIIF georeferencer extension. It’s not a closed ecosystem. People can adapt parts of it, create new tools, and use this open standard to create other things. In general, it uses modern web technology, and while this may not be modern 5 years from now, it allows us to do things that we couldn’t do 5 years ago.

IS: So far, what’s been the most exciting thing about developing Allmaps?

Demo of new Allmaps viewer that can load many maps of a single place at one time

BS: I’m currently working on a new version of Allmaps Viewer; it can draw hundreds (if not more) maps at the same time.

I’m also hopeful that the georeferencing metadata—the information that can be produced by annotating these maps and linking the annotations to the map’s existing metadata—can be preserved in archives, along with the existing digital maps. New tools will probably be developed to search, georeference, and view digitized maps in the coming years, but the georeferencing metadata that can come out of use of Allmaps will still be useful.

IS: We’ll be posting regular updates about Allmaps in our Map Center newsletters and on the website, but for folks who are excited about your work, what’s the best way to stay in touch with you?

BS: For now, the best way to keep updated about the project is to follow me on Twitter. And at some point, I’ll start publishing blog posts on the homepage of Allmaps and there’ll be a tool to discover collections of maps from different institutions.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.