This digital publication was supported by the Leventhal Map & Education Center’s Small Grants for Early Career Digital Publications program.

The opening of San Francisco’s Central Subway on November 19, 2022, marked a pivotal moment for Chinatown, standing as a testament to the enduring spirit of a historically marginalized community. As Malcolm Yeung, executive director of the Chinatown Community Development Center, noted, the Central Subway was a “signal to the city and the world that Chinatown is a permanent part of the fabric of San Francisco.” This event not only celebrated the completion of a 1.7-mile light rail system but also reflected a profound shift in the relationship between historically marginalized communities and infrastructure—a shift driven by strategic advocacy.

Activists on the Boston Common, protesting construction of the Central Artery in Chinatown (from Northeastern University Library Archives & Special Collections).

Chinatowns across America share the unfortunate narrative of destruction caused by infrastructure. Seattle’s International District, Philadelphia’s Chinatown, and Boston’s Chinatown are all witnesses to the divisive force of projects like Interstate 5, the Vine Street Expressway, and, in Boston, the Central Artery. The construction of these projects in the 1950s and 1960s tore apart social networks built over generations, forcibly evicting long-time residents and businesses and exacerbating the social isolation of marginalized communities.

The ramifications of infrastructural violence extend beyond physical displacement. The concept of “infrastructural stigma,” as articulated by Hanna Baumann and Haim Yacobi, underscores how stigma amplifies infrastructural failures and neglect in marginalized communities.1 However, a counter-narrative has begun to emerge—one where these communities refuse to be mere recipients of infrastructural violence. The response of marginalized communities to infrastructural challenges is evolving into a form of resistance, a reclamation of identity and a demand for inclusion in public spaces and networks.

In the case of San Francisco’s Chinatown, its leaders have defied expectations by embracing the Central Subway as an opportunity to redefine their community’s relationship with infrastructure. Unlike marginalized communities who often face the prospect of erasure through infrastructure projects, Chinatown’s leaders sought instead to advocate for infrastructure in order to place themselves firmly on the map. This seemingly paradoxical response necessitates a deeper exploration of the community’s existing social imaginaries and how they interact with the built environment.

To comprehend Chinatown’s response, it is essential to consider past experiences. Close encounters with the specter of erasure and displacement have shaped the community’s perspective, resulting in advocacy for infrastructural change.

In the shadow of the 1906 earthquake

On April 18, 1906, an earthquake struck San Francisco, toppling buildings and starting a fire that flattened the wooden structures in the city. As Chinatown burned, city officials wasted little time in forming the Committee on the Location of Chinatown to implement a plan created two years prior. This plan would evict Chinatown from downtown and relocate it to the southeast part of San Francisco, a remote corner of the city at the time.2 Immediately after the earthquake, the Committee of Fifty recommended street widening changes in the burned district, which had included Chinatown.

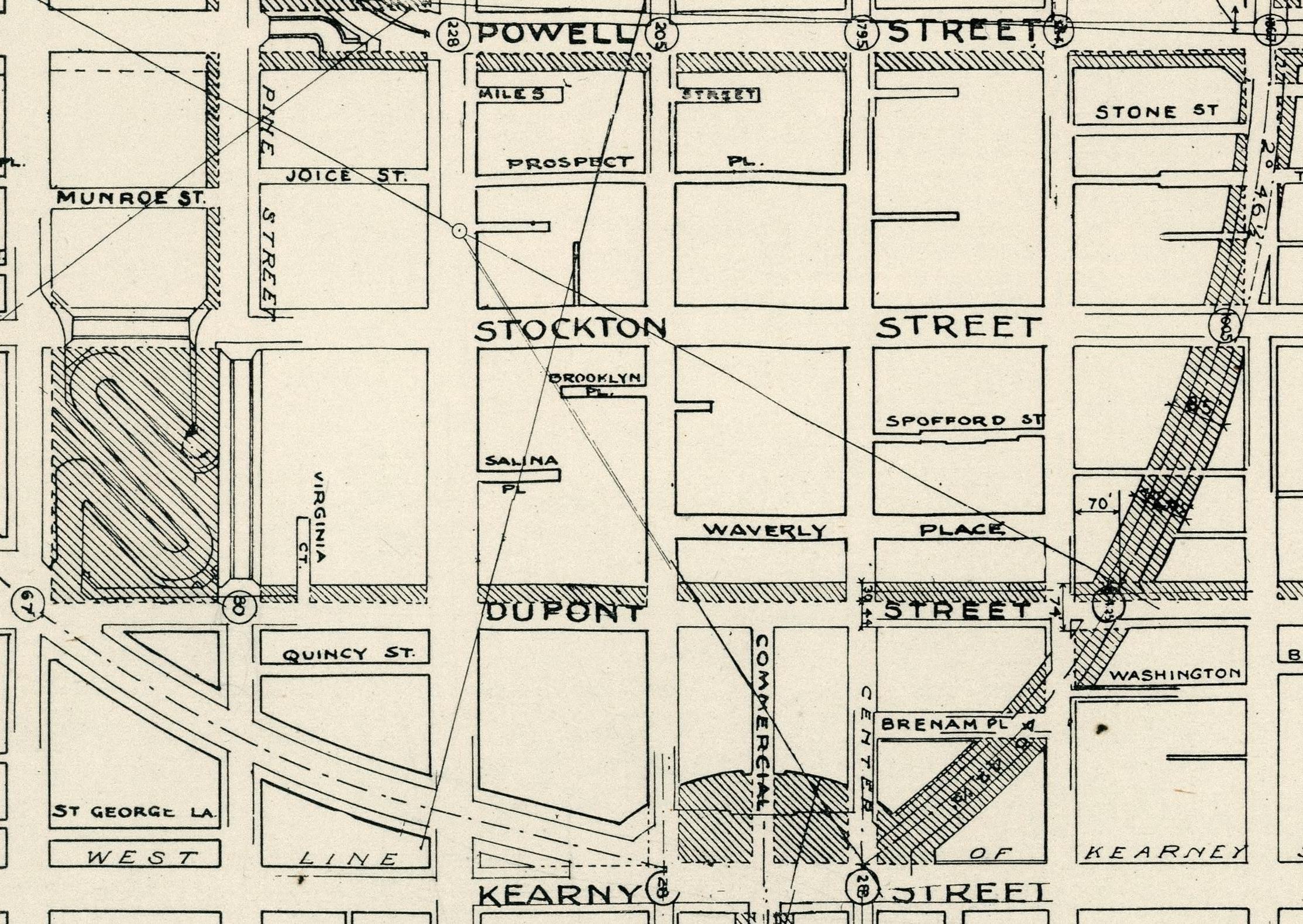

The 1906 addendum to the Burnham Plan for San Francisco shows the planned street widening for what is now considered core Chinatown, bounded by Powell Street to the west, Bush Street to the south, Kearny Street to the west, and Broadway to the north. These plans were never realized: largely due to a lack of funding and other immediate priorities in the aftermath of the earthquake, but more critically, because merchants in San Francisco’s Chinatown acted quickly.

Close up of proposed street widening changes. From Plan of proposed street changes in the burned district and other sections (1906), David Rumsey Map Collection.

In tense negotiations, Chinatown merchants threatened to leave for the neighboring city of Oakland and take their revenue-generating trade with them.3 They scrambled to rebuild their properties as quickly as possible, hiring White European architects who had never been to China to design ornate buildings with flared pagoda tops to flaunt an “Oriental” appearance. Through deliberate acts, perhaps over-exaggerating non-Chinese imaginations of Chinese heritage, merchants engaged in what amounts to “strategic Orientalism” as a strategy to remain in place.4

This rapid mobilization illustrated Chinatown’s astute self-awareness in recognizing the perspectives of outsiders but also suggested a pattern of community leaders capitalizing on such strategies in order to preserve the neighborhood and stay in place. In some ways, Chinatown merchants were keen to implement a self-defined idea of Chinatown that was internally consistent with its vision—and that of the city at large—of Chinatown’s necessity in San Francisco’s economy.

A scene from Chinatown in the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake (image accessed via OAC and courtesy of UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library).

In most traditional narratives, Chinatown would appear as the victim of infrastructural violence. Yet, if anything, Chinatown merchants after the 1906 earthquake created a counternarrative. Instead of further stigmatizing and solidifying Chinatown’s marginalization, community leaders of this period—through their advocacy and quickly rebuilding—illustrates how community leaders have capitalized on the idea of Chinatown, in order to fend off threats and ensure that Chinatown would thrive—and specifically, by leveraging acts of putting Chinatown “on the map.”

Chinatown merchants prevailed in their efforts. In spite of the near possibility of erasure, Chinatown constantly had a place on the maps of San Francisco throughout the twentieth century, particularly when it served the purpose of marketing Chinatown’s tourist appeal and attracting revenue to the city. The San Francisco Convention & Visitors Bureau put Chinatown on the map for its 1912 traveler’s guide in preparation for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition; it was also featured in Gus Schneider’s 1950 map of San Francisco’s Civic Center, showing Chinatown’s proximity to hotels in Union Square and Nob Hill.

In examining more recent examples of infrastructure advocacy, one might see how the idea of Chinatown as constantly one step away from physical eradication remains part of the modern imagination of Chinatown. Such anxiety is counterbalanced by the historical precedent that, when forced to defend itself against displacement, the community exhibited the ability to resist once again against external threats.

Crisis strikes again in the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake

Today’s Central Subway, a 1.7-mile underground light rail system, links downtown San Francisco’s bustling neighborhoods through four subterranean stations. Its path connects the South of Market to the convention and shopping hub, culminating in Chinatown—the second phase of the Third Street line, complementing the preceding 6-mile surface light rail in the city’s southeast.

This 1970 pictorial map depicts numerous landmarks and neighborhoods in San Francisco, notably including Chinatown adn the Embarcadero Freeway (courtesy of David Rumsey Map Collection).

The narrative of the Central Subway’s planning and advocacy unfolds across decades, in a story closely tied to the Embarcadero Freeway. Launched in 1959, the freeway aimed to create a crucial east-west link across San Francisco, connecting the city’s western neighborhoods to the iconic Bay Bridge in the east. In 1965, it expanded with additional ramps, including one adjacent to Chinatown, at Washington and Clay. The map of San Francisco to the left shows a pictorial depiction of both Chinatown and the Embarcadero Freeway in 1970.

This era witnessed the “Freeway Revolt,” a nationwide movement halting freeway projects that threatened urban neighborhoods. On November 5, 1985, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors voted 8-2 to initiate the Embarcadero Freeway’s removal, replacing it with a tree-lined boulevard and mass transit. A year later, this was followed by ballot propositions seeking the freeway’s demolition faltered due to fears of Chinatown’s adverse impact, which ultimately failed.5

After the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake damaged part of the Embarcadero Freeway, calls to build the Central Subway intensified. Environmentalists and backers of the 1986 ballot proposition saw this as a chance to remove the freeway. Mayor Agnos voiced support, dubbing it a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity– a chance to remove one of the worst blights on the face of any American city.”

Yet, for Chinatown merchants, the freeway was an “economic lifeline,” preserving accessibility and connection. Rose Pak, Chinese Chamber of Commerce leader, spearheaded the opposition, and was quoted saying, “It’s very arrogant to talk about aesthetics with this riding on the backs of workers and small businessmen… It’s not just a freeway, it’s our livelihood.”

On April 16, 1990, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors heard the proposal to demolish the freeway. Chinatown merchants, led by Rose Pak, closed their businesses for the day and showed up in droves to City Hall, decrying the potential removal as a threat to their livelihoods. The Board voted 6-5 to demolish, and the remnants of the freeway came down on February 27, 1991.

This demolition symbolized an existential threat to Chinatown. The Chinese Chamber of Commerce and merchants quickly rallied to restore their economic lifeline and turned their efforts towards infrastructural advocacy to replace the freeway, aligning with San Francisco’s plan for fostering a rapid transit network spanning throughout the city.

Modern map of the San Francisco metro, with the ‘Chinatown - Rose Pak’ stop at the north end of the red line.

In 1995, the San Francisco County Transport Authority unveiled the Four Corridor Plan, allocating 2 billion USD for new subway and rail infrastructure. Phase 1, a light rail route, connected southeast neighborhoods to downtown, and Phase 2, an underground subway, bridged the South of Market to the Financial District, Chinatown, and Fisherman’s Wharf. Chinatown merchants recognized the significance of this infrastructure, due to the fact that it would strengthen transit links within and beyond the neighborhood, bolstered by connections to BART and Caltrain.

Through the 1990s, Chinatown advocates, like Rose Pak and the Ping Yuen Resident Improvement Association, navigated hundreds of community meetings, championing the subway’s alignment and federal funding. The subway’s proposed route shifted, urged by Pak and the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, moving through Chinatown’s heart on Stockton Street.

The story culminates in success—the Chinatown station now bears Rose Pak’s name, marking her indelible impact on the community. The station’s design also embodies a culturally sensitive design by incorporating public art pieces, such as traditional Chinese paper cutting from an artist who was a resident of Chinatown’s single-room occupancy hotels.

Conclusion: A new chapter in the Chinatown story

In Chinese, “crisis” has two characters: 危机 embodying danger and opportunity at the same time. This meaning encapsulates Chinatown’s response to the crisis of the freeway removal period, defying the threat of physical erasure by advocating for infrastructure and permanently etching Chinatown merchants’ idea of the neigborhood onto the city’s map.

The story of Chinatown’s interaction with the Central Subway reflects a community that defies traditional expectations. In reframing its relationship with infrastructure, Chinatown’s leaders have shown that proactive engagement can transcend erasure and embrace empowerment. The completion of the Central Subway represents not only a milestone in transportation infrastructure but a milestone in advocacy—an assertion of permanence and significance.

By examining this narrative, this essay contributes to the discourse on marginalized communities and infrastructure. It underscores the need to appreciate the internal dynamics of these communities—their aspirations, strategies, and resourceful adaptations. As urban planners, policymakers, and community advocates seek equitable and inclusive development, San Francisco’s Chinatown serves as a powerful reminder of the potential of infrastructural advocacy. Through this lens, infrastructure becomes a conduit for empowerment, identity, and resilience.

Deland Chan is the Director of Research at the Chinatown Community Development Center. She is also a Clarendon Scholar at the University of Oxford, pursuing a DPhil in Sustainable Urban Development. She co-founded the Stanford Human Cities Initiative and previously taught courses on urban planning and sustainability at Stanford. Read more about Deland’s work on her website.

Notes

-

Baumann, H., & Yacobi, H. (2022). Introduction: Infrastructural stigma and urban vulnerability. Urban Studies, 59(3), 475–489. ↩︎

-

Ngai, M. M. (2006, April 18). San Francisco’s Survivors: How the Chinese Fought to Stay in Chinatown. The New York Times, Section A, Page 27. ↩︎

-

Chou, C. (2013). Land Use and the Chinatown Problem. UCLA Asian Pac. Am. LJ, 19, 29. ↩︎

-

Choy, P. (2012). San Francisco Chinatown: A Guide to Its History and Architecture. San Francisco, CA: City Lights Books.; Umbach, G., & Wishnoff, D. (2008). Strategic Self-Orientalism: Urban Planning Policies and the Shaping of New York City’s Chinatown, 1950-2005. Journal of Planning History, 7(3), 214–238. ↩︎

-

S.F. Votes to Save the Freeway. (1986, June 4). San Francisco Chronicle. ↩︎

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.