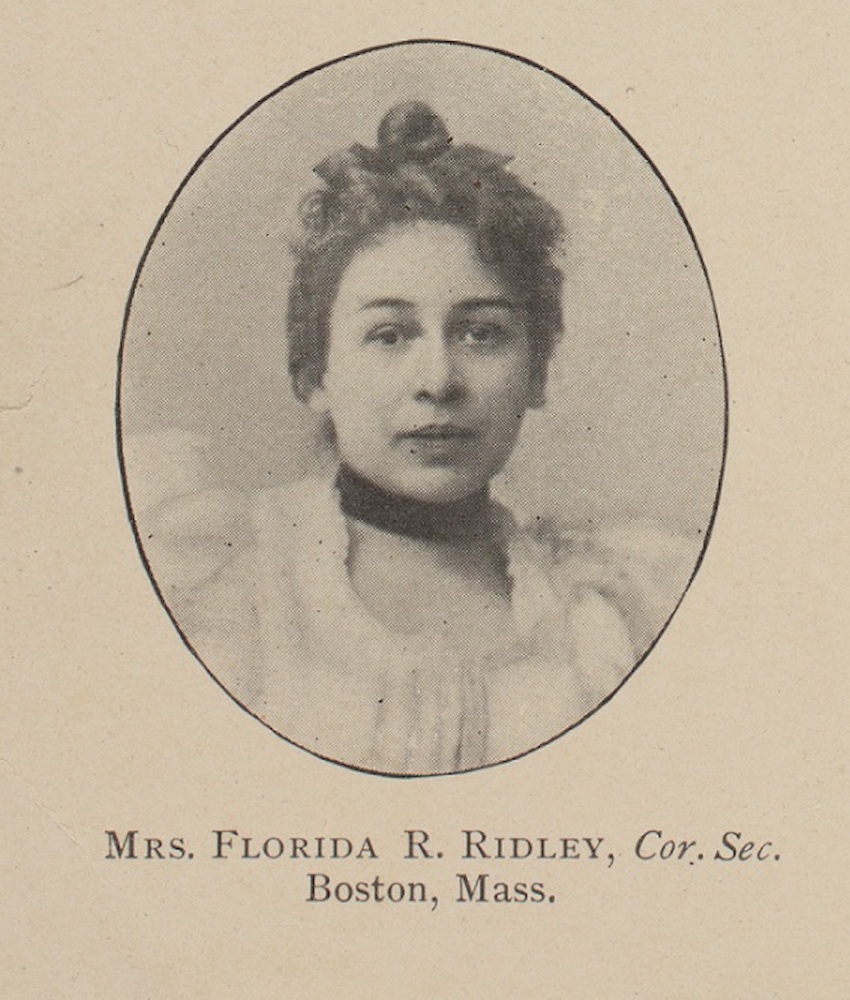

Meet Florida Ruffin Ridley

The maps in our featured exhibition, Building Blocks: Boston Stories from Urban Atlases, tell stories that are ultimately about people. You’ll see maps covered with the names of businesses, homeowners, and institutions, all of which show places built, inhabited, maintained, and enjoyed by people.

The stories of some people, however, are harder to find than others. In the case of Boston’s Black community, the urban atlases don’t always tell us as much as we might want to know. For example, the names of building owners are shown on the maps, but not those of renters. For various reasons, including racism, most Black Bostonians of the time did not own their own homes. However, they lived and worked throughout the city even though we may not see their names. To illuminate the lives and stories that sometimes run hidden through these maps, we follow the biography of an important Black Bostonian, Florida Ruffin Ridley, who worked, studied, played, and created within the landscapes on display.

Below, we follow Florida’s story and see how her life intersected with many other people and places in Boston and beyond.

Growing Up

Florida was born in 1861 and lived with her parents, George and Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, at the foot of Beacon Hill on Charles Street. Her father was the first African-American to graduate from Harvard Law School and the first Black judge in the United States. Her mother was a well-known activist, writer, and organizer for suffrage and against racial injustice.

Florida’s childhood was one of privilege. Her parents were financially well-to-do and highly educated, and so her early years were not representative of those of all Black children in the city. She attended the Grant School near her home, the same school where she would teach after receiving her credentials from the Boston Teachers College as a young woman.

Though Boston schools were integrated, the Black population of the city at the time was around 5%, compared with today’s approximately 20%. As a result, there were proportionally few Black students in classrooms. Students in Boston’s Putnam School, ca. 1890-1900.

After her own children were grown and out of the house, Florida began to write short stories. In 1926 she wrote about two thirteen-year-old boys, one Black (Arthur) and one white (Morton). In the course of the story, Arthur’s mother notes how in Boston’s integrated schools, students make interracial friendships, and the two boys seem to be close friends. But then the boys get into a physical fight, and Arthur’s mother learns about the reason for their dispute by eavesdropping on a conversation held by the boys’ friends outside her window:

“…what’d they fight about?”

“Well,” with deliberation, “Mort attacked Art’s good name, I’d fight for my good name, wouldn’t you—Mort tried to talk out of it but all the fellas were on Art’s side!”

“Sure, I’d fight for my good name—did he call him a liar?”

“Worse than that, he went to the guild and he had to report his good deed, and he said he had been ‘elevating a little colored boy!’”

Arthur’s mother considers the situation a few days later:

“…What had been [Morton’s] reaction from the fight? In his relations with Arthur, how much had he been influenced by adults? What were the parents’ reactions? Were they possibly those of the rebuffed missionaries who only feel pity that the heathen do not know what is good for them? As for my little son—I never discussed the matter with him. I felt he had shown himself wiser than I. With instinctive wisdom, he had sensed a situation to which I was blind, and had met that situation adequately.”

— Florida Ruffin Ridley, in Opportunity 3, January 1926

Creating Community

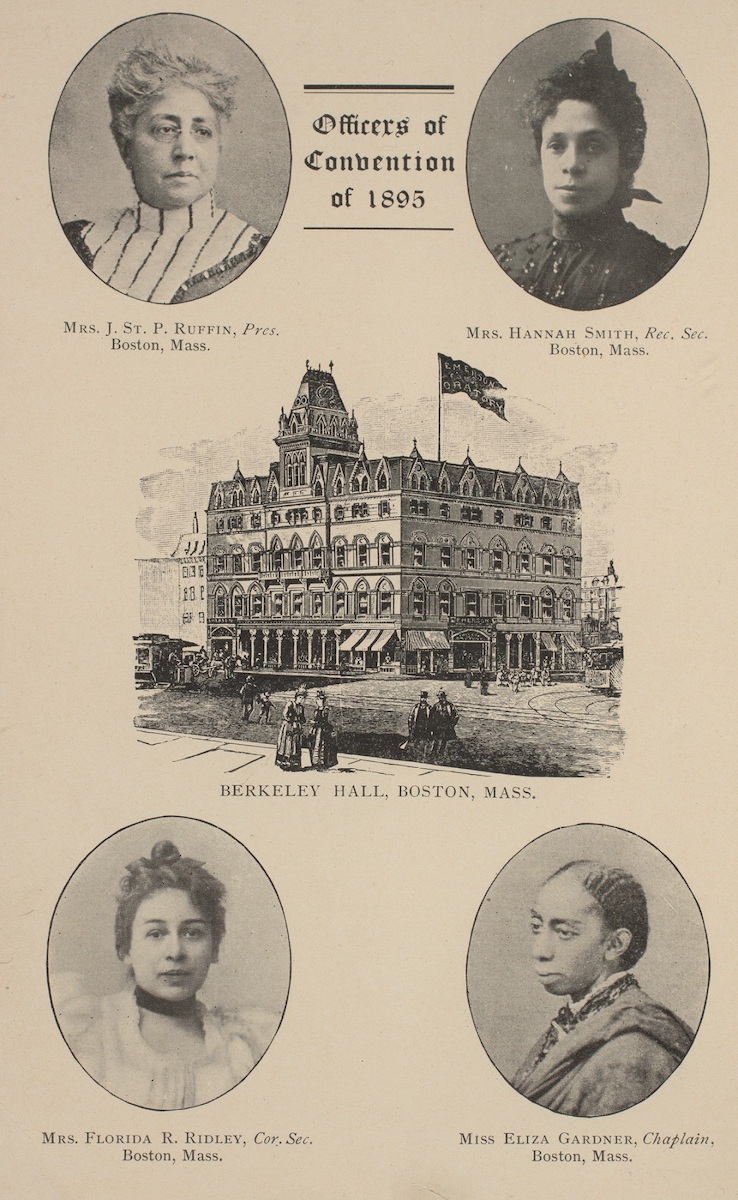

Florida appears here with her mother, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, as well as Hannah Smith and Eliza Gardner as Officers of First National Conference of Colored Women in Boston, 1895.

Florida is probably best known for her participation in the Black women’s club movement. As a founding member of the Woman’s Era Club, a Boston-based club started in 1894 by her mother, and later a member of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC), Florida wrote and organized around issues of the day—from promoting the arts to women’s suffrage. The club movement created a national community of women committed to promoting the well-being of Black people, with a particular emphasis on Black women. The motto of the NACWC was Lifting as We Climb to convey its dedication to racial uplift.

Women’s clubs are helping to bring us to a recognition of the truth that true dignity does not need barriers in order to preserve itself; that snobbishness is a vice, and that while friendship should be bound by congeniality, neighborliness should know no bounds. The club means the spirit of neighborliness with the world, the recognition of our duty toward our neighbor, and not only of our common humanity but our common divinity; the club helps us not only to make the best of that within us but to see the best of that in others.

— Florida Ruffin Ridley, Woman’s Era, Oct-Nov, 1896

In 1895, Florida and her mother were principal organizers of the First National Conference of Black women’s clubs. The convention was held in Boston in Berkeley Hall, also known as the Odd Fellows Hall. Women from 14 states gathered to form a national organization. They created committees to address issues such as lynching, convict leasing, segregation and temperance. They listened to speeches from national activists, Black and white, such as Booker T. Washington and William Lloyd Garrison, Jr. The convention then moved to the Charles Street Church to finish their organizing, just a block from the Ruffin home.

Taking Care

In 1918, Florida, her mother, and Maria Louisa Baldwin founded the League of Women for Community Service, and soon after purchased a building at 558 Massachusetts Avenue in the South End. Initially intended to support Black soldiers during World War I, the League went on to fill many civic roles, including housing Black female students attending Boston’s universities. While attending the New England Conservatory, Coretta Scott lived in the building when dating Martin Luther King.

Organized charity work was a foundational focus of Black women’s clubs. These relatively well-educated and affluent Black women actively engaged the fight against the struggles facing Black Americans and felt it was their responsibility to use their advantages to care for others. Florida wrote in The Woman’s Era about hosting a hospital fair followed by a “special effort for St. Monica’s Home, for sick and destitute colored women and children” whose “receipts were more than sufficient to supply the Home with all of its fuel for the year.”

Florida worked with her mother, Josephine, to create The Woman’s Era, the first national newspaper published by and for Black women in the United States.

The clubs also expressed care for the community by denouncing and organizing against the violence and racism that Black Americans faced. Ida B. Wells, who worked alongside Florida and her mother in founding the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, was a powerful anti-lynching advocate. In this open letter responding to British reformer Laura Ormiston Chant’s opposition to a Unitarian church resolution denouncing lynching, Florida uses her voice to speak out against racist terrorism:

In the interest of common humanity, in the interest of justice, for the good name of our country, we solemnly raise our voice against the horrible crimes of lynch law as practiced in the south, and we call upon Christians everywhere to do the same or be branded as sympathizers with the murderers.

— Florida Ruffin Ridley, Woman’s Era, June 1894

Having Fun

As part of her leadership for the League of Women for Community Service, Florida was committed to celebrating and raising awareness about Black artists. She sponsored performances of amateur theater, chorales from Black colleges, and classical performances, as well as art exhibitions. Her exhibitions include one hosted at the Boston Public Library in 1922. Her own brother George Ruffin was an accomplished singer and performed around Massachusetts.

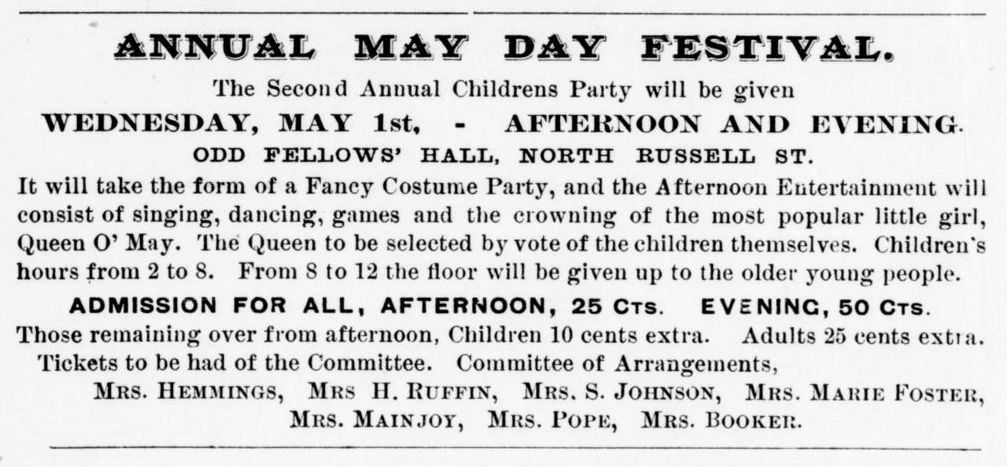

As a young child, and then as a mother with children of her own, Florida might have participated in a May Day celebration like this one organized by many of the women she knew and advertised in the Woman’s Era magazine in 1895:

The Harriet Tubman House in the South End, a settlement house founded by six Black women to provide housing for recently arrived southern Black women, hosted a series of “Musicales” organized by Florida and the League of Women for Community Service in 1919.

Making and Trading

Next door to Ulysses’s shop, the Colored American Magazine operated out of 5 Park Square.

For the majority of Black Bostonians in Florida’s lifetime, especially those who had recently migrated from southern states, racism presented a formidable barrier to stable employment. Black men in Boston often worked as bootblacks, janitors, laborers, servants, waiters, and porters, while women often found work as cooks, maids, seamstresses and nursemaids. Boston’s Black entrepreneurs operated businesses that employed Black laborers, organizing many of them to engage in collective political action.

The maps in this exhibition rarely show us the names of Black businesses, but we can use other kinds of sources, like city directories and newspaper advertisements, to uncover their stories. For example, Florida’s husband Ulysses A. Ridley ran his tailoring business at 212 Pleasant Street in Boston’s Park Square, advertised here in the New York Age newspaper. Next door to Ulysses’s shop, the offices of the groundbreaking Colored American Magazine bustled as they published new African-American literature and articles protesting racial injustice.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.