Meet “The NAREB Map”

During my second week at the LMEC, I came across a curious object in our digital collections. Pseudo-Gothic lettering, striking primary colors, a pair of coats of arms: at first glance, it was easy to mistake this 1926 map by Ignatz Sahula for something a bit more, well, medieval than it actually is.

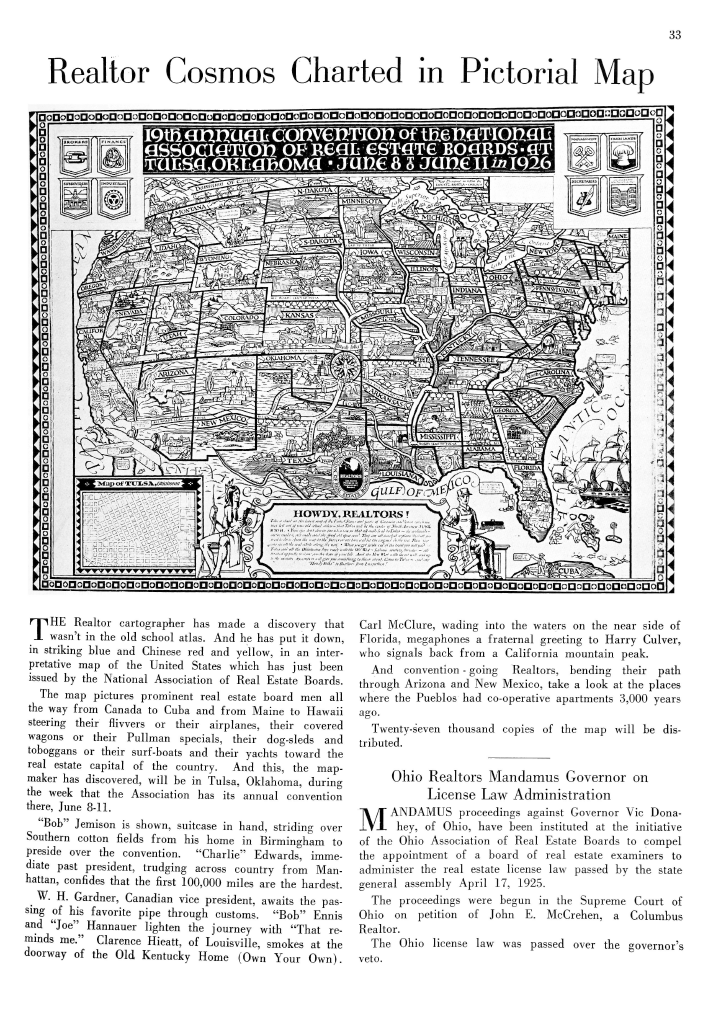

From our collections, the NAREB map: a pictorial map advertising the 19th annual convention of the National Association of Real Estate Boards.

Pictorial maps were popular throughout the twentieth century, but this one—let’s just call it the NAREB map, short for National Association of Real Estate Boards—has been called one of the “earliest, largest, and most colorful of all American pictorial maps.”1

That statement is probably a little exaggerated, since this style of pictorial map had been around for decades by 1926, but the NAREB map remains a fascinating object for all sorts of reasons.

In it, we find Realtors2 across North America flocking to Tulsa, Oklahoma for NAREB’s annual convention. Local board representatives wisecrack about their colleagues, and each state spotlights a well-known trope (or two) for which it’s known. Watchful eyes pockmark a sack of Idahoan potatoes; in Wyoming, horses draw a covered wagon east . It’s not all sunshine and corn stalks, though, evidenced by the map’s racist rendering of a Black man in Mississippi .

Landing at the intersection between mapping and art, pictorial maps like these were often produced to be eye-catching and attention-grabbing. It doesn’t really matter that Ignatz Sahula omits geographic features like Virginia’s Eastern Shore; his primary objective isn’t preserving shape or area, but rather connecting emotionally with an audience. He doesn’t need the Eastern Shore to convince the nation’s Realtors that, if they miss this year’s convention in Tulsa, they’ll be missing out on much, much more.

‘Howdy, Realtors!’ A message explaining in greater detail how all roads lead to Tulsa.

It’s always exciting to discover something like the NAREB map (and with nearly 10,000 cartographic objects digitized at the LMEC, there’s no shortage of other discoveries waiting to happen). Beneath its garish colors and its bevy of inscrutable “you-had-to-be-there” jokes, the map actually has quite a lot to tell us about the politics of race, real estate, and urbanization in the early-twentieth century US.

The Roads

In the late 1800s, the term “Realtor” did not exist. In fact, the term “real estate broker” had only entered the American lexicon in the mid-nineteenth century. Around this time, it had less-than-flattering connotations. In popular magazines and newspapers, real estate brokers were commonly portrayed as curbstoners: devious swindlers who took advantage of unwitting newcomers to a city.3

It wasn’t until the formation of the Chicago Real Estate Board in 1883 that the job of a real estate agent began to cohere as a respectable profession. Attempting to dispel the popular image of real estate brokers as grifters and cheats, the Chicago Board initiated a campaign to “professionalize” the real estate industry. In doing so, they established many tools that still exist today, including the standard lease, the Realtor’s Code of Ethics, and the multiple listing service.

These tools were meant to standardize a form of professional behavior in the real estate industry, but professionalism came at a cost. For example, Article 34 in the 1924 NAREB Code of Ethics instructed Realtors to “never [introduce] into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.” Such practices led inevitably to spatial racism which took the form of redlining, blockbusting, and racial covenants.

The 1926 NREJ contains a reprint of the NAREB map, with text encouraging Realtors to come to Tulsa. Courtesy of the National Association of Realtors’ archives.

By 1908, the National Association of Real Estate Exchanges had held its formative meeting in Chicago—the first of many annual conventions to come. These conventions were heavily publicized in the NAREB’s flagship journal, the National Real Estate Journal, through features like songbooks, postcards, and of course, the NAREB map. In a 1926 edition of the NREJ, the editors reprinted Sahula’s map above the following text:

“The Realtor cartographer has made a discovery that wasn’t in the old school atlas. And he has put it down, in striking blue and Chinese red and yellow, in an interpretative map of the United States which has just been issued by the National Association of Real Estate Boards.”

As Jeffery Hornstein argues, “The annual convention played a central role in the development of a national orientation and professional consciousness… The journey to and from the convention was an expressive rite of passage, a trip away from everyday domestic and business concerns for the large majority of men who left wife and children for the exclusive world of real estate men.”4 No wonder, then, that the roads to Tulsa are so prominently highlighted in the NAREB map—professionalization, it seems, was as much about the journey as the destination.

The Destination

Tulsa in 1926 was significant for a number of reasons. For one, at the time this map was made, real estate in Tulsa was on the up and up.5 The city was in the second wave of an oil boom that had begun in 1905 and had firmly established Tulsa as the “Oil Capital of the World”. This created a “boom town” effect: the city, including its real estate, became desirable quite suddenly.

This 1923 map of Highways through the great oil, gas, mining, industrial, & agricultural areas of the United States, from the Library of Congress’ collections, features Tulsa prominently.

At what cost this happened is hard to overstate. What’s known today as Tulsa was settled by the Lochapoka Tribe in 1828 after the forcible expulsion from their native land in present-day Alabama during the violent period of Indian removal. “Real estate”—that is, the concept of land as a discrete and bounded commodity—always comes from somewhere, and indigenous dispossession is baked into the very DNA of the real estate industry.

Furthermore, the 1926 convention came just five years after the Tulsa Race Massacre, when a white mob destroyed “Black Wall Street” in Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood. The Greenwood district is conspicuously left off of the NAREB map’s Tulsa inset, despite being less than one mile from the Mayo Hotel, where the convention was held. All that to say: while real estate in Tulsa may have been booming, these kinds of booms come with a lot of baggage.

The convention in Tulsa was also significant for what was discussed there. At the 1926 conference, NAREB began co-authoring a joint statement on principles of subdivision control with the American City Planning Institute (ACPI). While this may sound bland, Marc Weiss notes that the “NAREB-ACPI joint statement… was so influential that it formed the basis of the U.S. Department of Commerce’s A Standard City Planning Enabling Act.”6

In an era where urban populations were rapidly increasing, and city planning was rapidly becoming a scientific endeavor, NAREB was much more than a mere trade organization. In Tulsa, 1926—and beyond—NAREB played an active role in turn of the century American city planning.

The Ballad of the “Binder Boys”

Tulsa wasn’t the only place in the midst of a realty boom in 1926—in fact, it wasn’t even the only boom town depicted on the NAREB map. Just take a look at southern Florida:

Florida and its environs as depicted on the NAREB map.

In proper comic book fashion, Tampa and Miami are literally booming , while nearby, a real estate man kicks the pants off a pair of “binder boys.” Associated with the Miami land boom of the mid-1920s, the binder boys were consummate curbstoners. After “binding” the purchase of a property parcel with a ten percent down payment, on which the remainder wasn’t due for thirty days, the boy would turn around and sell his binder at a markup. Sometimes the same note of ownership would be transacted 7 or 8 times in a single day, each time the price going up.7

The binder boys operated for 5 months during the summer of 1925, but their feverish day trading of real estate serves as a microcosm for Miami’s wider urban politics. At the turn of the century, Miami was still a new US city, and many—not just the binder boys—viewed its real estate as a guaranteed profit machine.8 As Julio Capó Jr. has explained, turn of the century Miami was aggressively marketed by urban boosters as a transgressive “fairyland.” As it turned out, the fairyland was a bubble in disguise, and in 1926, it did what bubbles do. Nevertheless, the real estate industry churned forward. Surely it’s no coincidence that the 1927 NAREB convention would be in—you guessed it!—Miami.

According to one account of the Miami land boom, “The butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker, and their wives, will buy a lot for you, or sell you one.”9 If everybody was hustling for real estate, then why were the binder boys singled out as bad actors? Perhaps those consummate curbstoners earned their spot on the NAREB map not because of what they did (e.g., land speculation), but rather because of how they did it: without professionalism.

Cartography and the nation

Choosing where and how to enumerate boundaries is a fundamental question in cartography and mapmaking. Ignatz Sahula was trained as a painter, not a cartographer—but he still manages to make some interesting representational decisions about boundaries.

Looking to the northern border, we can presume that Canada was well-integrated into the professional community of Realtors at the time this map was made. Squatting in southern Ontario, William H. Gardner looks forlornly toward Minnesota, wistfully declaring, “I hope they’ll let my pipe through the customs soon—I want to get to Tulsa.” Elsewhere, a man named Goodwin Gibson catapults past Toronto on a sled: “I believe in international multiple listing,” he says.

The US-Canada border on the NAREB map, complete with bobsleds and characters.

While we only get a small glimpse of the Canadian state, it’s stylistically rendered just like the rest of the US. It has named characters, snowy mountains, little houses, and pine trees. Despite being separated by a national border, Sahula uses style and color to imply that Canada and the US are connected by climate, culture, and commerce. He does the same in Cuba, where a fedora-clad Roberto Salmon exclaims, “We want Realtors in Havana in 1927.”

In 1926, NAREB clearly viewed Canada and Cuba as potentially profitable real estate markets. The same cannot be said of Mexico. The basic cartographic design principle of contrast instructs us to use bright colors to attract attention, and dull ones to avoid it. Here, everything south of the Rio Grande is painted in a pallid gray-brown. Compositionally, Mexico is also given a flyover status. In addition to being positioned underneath the title cartouche10 and the Tulsa inset map, Mexico is literally being flown over by a plane coming in from Hawai’i —complete with a classic map monster. Even though the term “flyover country” wasn’t coined until long after the NAREB map was made, the implication here remains clear: in a scene bursting with busy-ness, Mexico is left to quietly fade into the background.

The US-Mexico border on the NAREB map, designed to be unobtrusive.

All roads lead to…

Eventually, NAREB became the National Association of Realtors. It remains the leading organization for professional real estate brokerage, and they still hold their annual convention in a different city each year. Since 1926, however, I’m not sure if they’ve made another map quite like this.

Notes

-

Hornsby, Stephen J. 2017. Picturing America: the Golden Age of Pictorial Maps. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 186. ↩︎

-

As of 1950, the term REALTOR® was trademarked with the US Patent Office by the National Association of REALTORS®. In this article, for ease of reading, I’m simply going to type “Realtor.” ↩︎

-

Hornstein, Jeffrey. 2005. A Nation of Realtors®: A Cultural History of the Twentieth-Century American Middle Class". Durham, NC: Duke University Press, pp. 13-15. ↩︎

-

Hornstein, p. 32-35. ↩︎

-

It’s worth noting that the 1926 convention came just five years after a white mob’s destruction of “Black Wall Street” in Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood, more commonly known as the Tulsa Race Massacre. ↩︎

-

Weiss, Marc A. 1987. *The Rise of the Community Builders: The American Real Estate Industry and Urban Land Planning." New York, NY: Columbia University Press, p. 75. ↩︎

-

George, Paul S. 1986. “Brokers, Binders, and Builders: Greater Miami’s Boom of the Mid-1920s.” The Florida Historical Quarterly, 65.1, pp. 35. ↩︎

-

Capó Jr., Julio. 2017. Welcome to Fairyland: Queer Miami Before 1940. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 104-105. ↩︎

-

Capó, p. 105. ↩︎

-

The depiction of the Native American man on the cartouche is consistent with noble savage stereotypes that were common at this time. ↩︎

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.