This article is part of the Map Chats series commissioned by Richard Pegg, Director and Curator of the MacLean Collection in Illinois. For more, see all the Map Chat articles published by the Leventhal Center.

On this overglaze enamel ceramic map plate made in the first half of the nineteenth century, only twenty small named islands surround the main islands of Japan—far fewer than the more than 10,000 islands that exist. These particular twenty islands were intended to participate in a physical and psychological protective ring around the Japanese archipelago to protect it from foreign pressures of the outside world. One island in particular, Yoshishima, or Yoshi Island , is also associated with an encounter with European sailors in the late eighteenth century.

Enameled ceramic map plate, ca. 1800–1850. MacLean Collection, MC29791

It was June 1787. A fleet of two ships battled severe weather and poor visibility in the sea between the Chinese continent and the Japanese island of Honshū, the latter known for its vigorously-enforced policy of repelling foreign ships. One fleet was French, commanded by Jean-François de Galaup La Pérouse, who, relying for navigation on the latest European scientific instruments, was able to navigate despite the low visibility and the relatively limited charts that were available to him. When the weather cleared, the expedition observed a barrier island near Cape Noto—today’s Noto Peninsula.

The Noto Peninsula on a 1905 map of Japan

La Pérouse and his crew were the first Westerners to sight this “completely unknown to Europeans” area along the northern coast of Japan. A map of La Pérouse’s route on that voyage records the location and date of that encounter.

On the sixth of June, they passed within a stone’s throw of a small island which they identified as “Jootsi-sima,” and which they described thus:

“The island is small, flat, well wooded, and pleasing to the eye. I do not think its circumference exceeds two leagues. To us it appeared well inhabited. Between the houses we observed edifices of considerable size; and near a castle, seated on the south-west point, we distinguished gallows, or at least posts, with a large beam placed across them at top. Possibly, however, these posts had a very different designation; for it would be singular, if the customs of the Japanese, so different from ours, resembled them in this point.”

Jean-François de Galaup La Pérouse, Chart of the Discoveries Made in 1787, in the Seas of China and Tartary, by the Boussole and Astrolabe, Map 46 (1797). MacLean Collection, MC26569

This essay follows the story of this incident and complicates the deceptively simple description recorded by La Pérouse. It specifically addresses two points: the process of correlating direct observation with existing cartographic information, and the interpretation of such observations in a cross-cultural context. The first relates to the history of science, in which La Pérouse was a prominent figure. His expedition has been singled out by Bruno Latour as representative of the Enlightenment project of collating “immutable mobiles”—in this case, mass-produced maps whose information remained stable over time. Latour’s evaluation rests on the assumption that the data collected by La Pérouse was sufficiently accurate to advance previous knowledge. The second point examines the tension between how Europeans interpreted the island that they saw from a distance and the entirely different understandings which existed within a Japanese cultural and geographical context.

Finding Yoshishima

In 1798, the editor of the official account of La Pérouse’s voyage included a footnote to the description of the island:

“Geographers have hitherto given the name of Jootsi-sima to the island lying to the N.E. of Cape Noto. La Pérouse gives the same name to another island seen by him five leagues to the N.W. of that cape, and which is laid down in all the charts without a name. I know not whether this proceeds from an error of La Pérouse, but I thought it necessary to caution the reader against a mistake that might arise from two islands of the same name, being laid down so near the same Cape.”

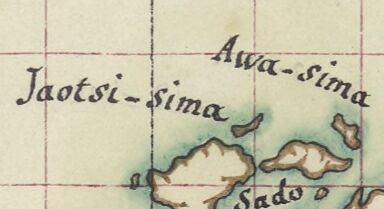

Detail from John Pinkerton, Korea and Japan (1809; 1815 ed.). David Rumsey Map Collection

European mapping of this island thus became confused. Which island was properly named? This confusion of two like named islands is reproduced on John Pinkerton’s 1809 map of Japan which includes one island named “Jootsi Sima according to La Pérouse " and the other “Jootsi Sima according to Roberts”—the cartographer of James Cook’s third voyage.

Detail, Charles-Pierre Claret de Fleurieu, Copie de la carte manuscrite originale dressée par ordre du roi, pour le comte de La Pérouse (1790). Bibliothèque nationale de France

But what was the source of the name used by La Pérouse to identify the island? The manuscript chart of the Pacific prepared specifically for the expedition has only one island named Jaotsi-sima to the northeast of the peninsula, with a small unnamed island off the west coast of the peninsula mentioned in the 1798 official account.

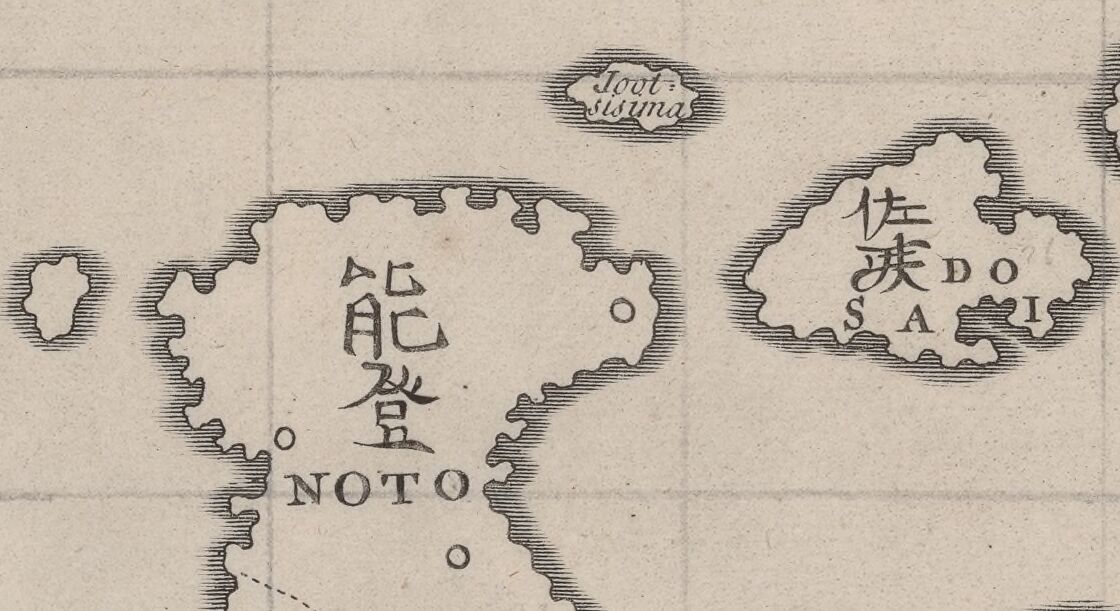

La Pérouse would have had access to earlier French versions of the map of Japan from Johann Gaspar Scheuchzer’s 1727 translation of Englebert Kaempfer’s groundbreaking History of Japan, which also shows only the named northeastern island (as “Joot sisima”) and a small unnamed island on the west coast of the peninsula.

Detail of Johann Gaspar Scheuchzer, Imperium Japonicum (ca. 1700s). Bibliothèque nationale de France

Scheuchzer in turn worked from two versions of maps brought back from Japan by Kaempfer. These maps referenced earlier maps of Japan from the seventeenth century, where the island appears northeast of the Noto peninsula as Yoshishima ヨシシマ (or “Yoshi island”).

![Yoshishima in the upper right corner, Detail of manuscript copy of Ishikawa Ryūsen (石川流宣), Honchō zukan kōmoku [=本朝圖鑑綱目] (1687). Bibliothèque nationale de France](https://gallica.bnf.fr/iiif/ark:/12148/btv1b7200260b/f5/551,2375,3724,2375/full/180/default.jpg)

Yoshishima in the upper right corner, Detail of manuscript copy of Ishikawa Ryūsen (石川流宣), Honchō zukan kōmoku [=本朝圖鑑綱目] (1687). Bibliothèque nationale de France

Aoyama Hiro’o, the foremost expert on the early mapping of the Japanese periphery, has a convincing origin theory for the “Yoshishima” toponym: earlier maps feature an island named Tonoshima (止之島), whose characters when written in cursive script could be misread as Yoshishima (よし島). That (mis)reading could have made sense either as a transcription of “Yoshi” the character for “reed” (葭), describing a generic low-lying “reed island,” or, more plausibly, as “Yoshi” meaning “good” or “auspicious” island. Some of the confusion in the naming of this group of islands in Japan was thus carried over to European maps. When transcribed onto European maps, toponyms from Japanese maps were rarely verified through direct observation.

Which island did La Pérouse see?

Even though the island identified by La Pérouse was cartographically ambiguous, it should still be possible to identify the actual island by its (current) Japanese name. The editor of La Pérouse’s journals in English, John Dunmore, gave two suggestions: the first is Nanatsushima (七つ島), a group of hilly islets lying 20 miles off Cape Noto. The second is Hegura-jima (舳倉島), a larger island further away. Dunmore preferred Nanatsushima, and that identification stuck for some time. But this choice is problematic as the Nanatsushima group was never inhabited, and the only structure on it is a modern lighthouse. Hegura-jima, on the other hand, matches La Pérouse’s description: flat, roughly the same length, bordered by cliffs on its Western side, and, most importantly, inhabited. In the early modern period, entire families would move from Wajima town on Noto to Hegura in the beginning of June for the fishing season. To this day, the fish market in Wajima, where fisherfolk from Hegura bring their catch, is famous throughout Japan for the quality of its seafood.

Chinese trade ships off Miura bay in Sagami province in 1578; this is how most early modern Japanese would have visualized news of approaching foreign ships. From Miura Jōshin, Hōjō godaiki (北条五代記, “Record of the Five Reigns of the Hōjō”), vol. 10 (1659). Cambridge University Library

Consider the perspective of the Japanese who saw La Pérouse’s ships passing by the island. This may have been the first time the fishermen of that area had seen a European ship. Were they alarmed, curious, or both? When considering a local point of view, it is helpful to keep in mind that islands such as Hegura were among a number of peripheral territories which played an apotropaic role—in other words, they were seen as protections against evil—which formed a physical as well as psychological barrier against outside intrusion. Most Japanese commentators agree that Neko no shima (“Cat Island”), mentioned in a story in the 14th century compilation Konjaku monogatari shū (今昔物語集, Tales of Time Past) is Hegura island. Compare its description below with La Pérouse’s description:

“[…] in Noto Province, there was a ship's captain named —no Tsunemitsu. He went to this island when he was blown out to sea. The inhabitants came out and would not allow him to land. They let him moor his boat for a time by the shore and gave him provisions. Within seven or eight days a wind sprang up from the island, whereupon his boat raced swiftly back to Noto Province. Afterwards the captain said, ‘Far off in the distance row upon row of dwellings and streets like the lanes of the capital were faintly visible, and there was much traffic to and fro.’ Very likely it was to prevent him from observing the island more closely that they would not let him land. In recent times, when Chinese sailors come from afar they first call at that island to take on provisions and catch fish and abalone. From there they set out for the port of Tsuruga on the mainland. In like manner, these Chinese have been forbidden to tell anyone that such an island exists.”

This anecdote confirms that by the time the Europeans arrived, there was a long tradition of repelling outsiders from peripheral islands as a first line of defense around a “sacred” Japanese space. Locals had also negotiated with Chinese ships, whose encounters were depicted in woodblock books in the late sixteenth century, and so the French ships were not the first foreign vessels to reach these waters.

There is another important detail in La Pérouse’s description: a wooden structure which he tentatively likened to gallows. This was as perhaps an echo of illustrations of Japanese martyrs in the past found on European maps such as Jodocus Hondius’s 1606 edition of the map of China in Mercator’s atlas.

Jodocus Hondius, Map of China (1606). MacLean Collection, MC5805

La Pérouse was right to doubt his own interpretation: the structure he saw was most probably a wooden tori’i gate marking the entrance to a shrine. The only island with a shrine in the area was the Hegura, which featured a shrine dedicated to the deity Okitsuhime. The shrine is particularly ancient: it is mentioned in the 927 CE compendium of ritual instructions Engishiki (延喜式), which means it was recognized as an official shrine by the Imperial Court. An eighth-century bronze mirror associated with rituals of safe sea passage, distributed from the capital to strategic locations on the edges of the premodern Japanese polity, has been found at the shrine. The shrine and its tori’i gate served as visible signs in a similar apotropaic role to that of other peripheral territories themselves on premodern maps of Japan. Just like Yoshishima, Hegura had a border function, not only in geographical but also in sacred terms: to protect the edges of the realm against outside forces. From that perspective, La Pérouse's sail-by would have been interpreted as a narrowly avoided intrusion into the sacred realm. The protective sacred infrastructure embodied by the shrine had done its job.

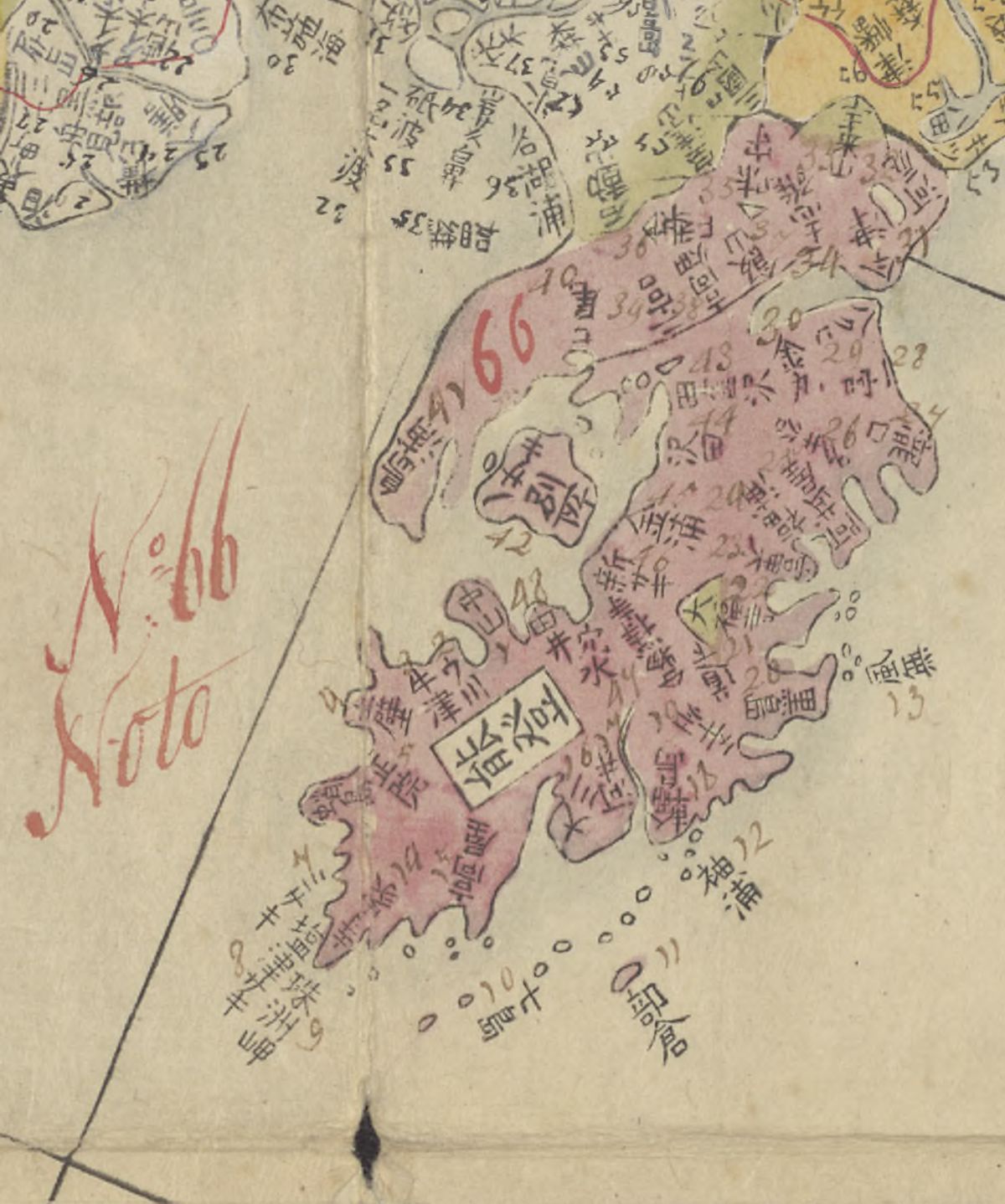

Yoshishima shown in blue on the bottom (north is oriented “down” here to read the toponyms) with Cape Noto in blue above.

For the fishermen of Hegura, space was organized topologically: their island was historically protected by a shrine connected to another shrine in Wajima town. And Hegura, along with Yoshishima, participated in a network of peripheral territories protecting the main body of the Japanese archipelago. That network was still relevant in the 1830s up till the 1850s, when Yoshishima was included in the maps of Japan featured on ceramic plates—including the one which formed the starting point for this essay.

Puzzles and mysteries

Could La Pérouse have identified the island more accurately if he had access to better maps? In 1779, the neo-Confucian scholar Nagakubo Sekisui (1717-1801) published a map of Japan that far surpassed Ryūsen’s, with over five times as many place names. If we overlay Sekisui’s map onto La Pérouse’s map, it becomes clear that La Pérouse saw and described Hegura island (written as 部倉), not Yoshishima.

Hegura annotated as no. 11 on detail of Nagakubo Sekisui, Nihon yochi rotei zenzu 日本余地路程全図 (1779). Leiden University Libraries.

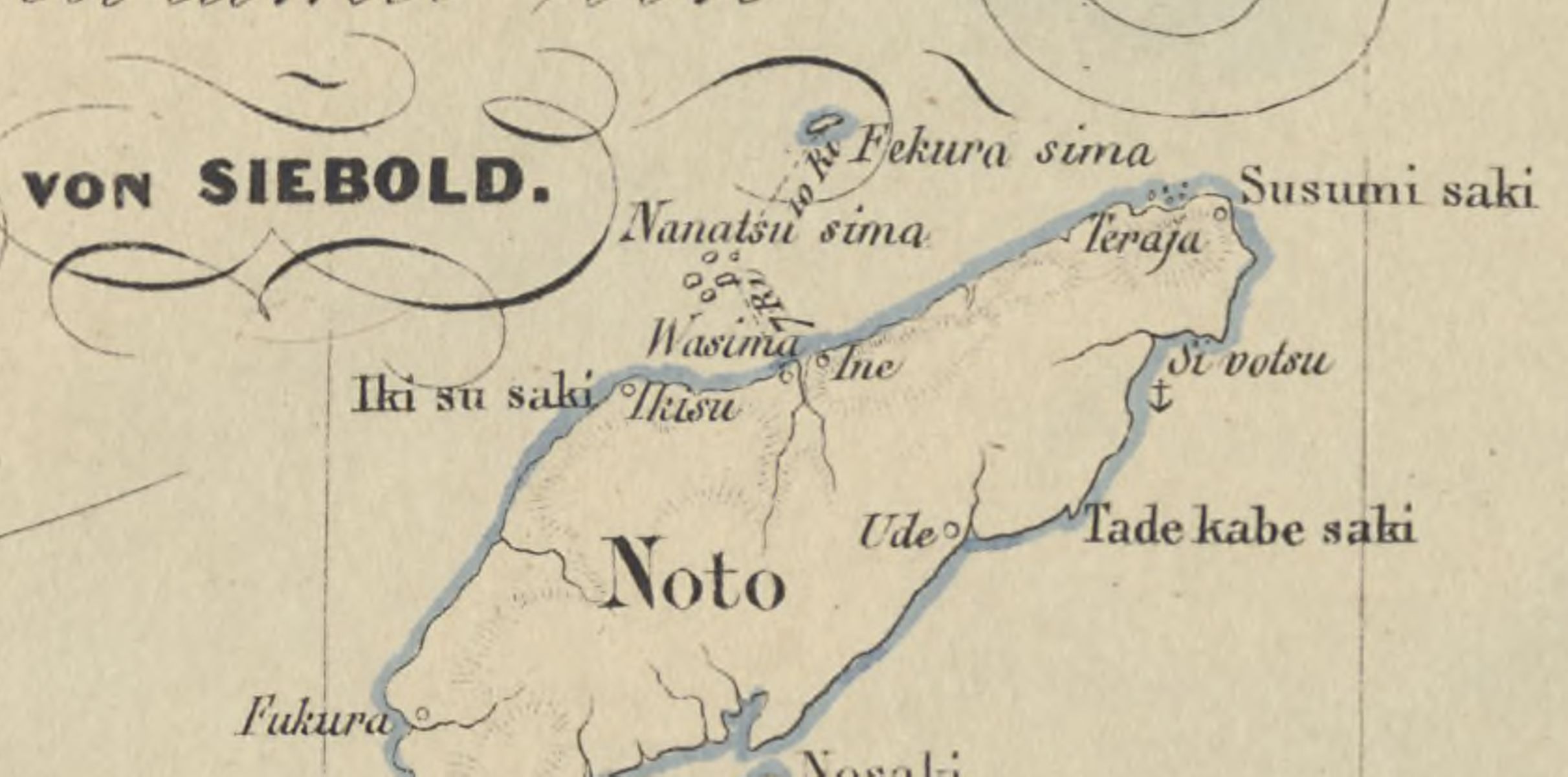

In theory it could have been possible for La Pérouse to have access to this map, but it was only in 1792 that the first known copy reached Europe: it was acquired by the scholar and Dutch East India Company merchant Isaac Titsingh during his 1779-1784 stay in Japan, who then sent to his brother Jan in Amsterdam. It was eventually acquired by Philip Franz von Siebold, another scholar and surgeon for the Dutch East India Company in Japan between 1823 and 1829, and is now kept in the Leiden University Libraries. Siebold consulted Sekisui’s map for his own maps of Japan, and this allowed him to state that La Pérouse’s Jootsisima “is actually Fekurasima.”

Detail of Philip Franz von Siebold, Karte von Japanischen Reiche (1840). Leiden University Libraries.

Both La Pérouse and Siebold made judgements based on the maps available to them. Cartographic references were coupled with a topographic approach to space: if a specific geographical feature could only be placed in one distinct location, then the task was to better establish that location in mapped space. They were both trying to solve a puzzle, for which more information meant better judgements. But as Malcolm Gladwell reminds us, the challenge is often rather to solve a mystery: to make sense of the abundance of available information. In the case of Yoshishima, rather than determining where it was and which name to call it, it was more important to understand what kind of island it was. For example, can the concept of “hyper-insularity,” developed to describe contemporary marginal islands in Japan, be extended to discuss the premodern apotropaic dimension of Hegura and Yoshishima?

La Pérouse has long been understood as typical of the spirit of the Enlightenment and a pioneer of modern science. The information he brought back, in the form of what Latour calls “immutable mobiles,” facilitated scientific advancement in European metropolises. That view has been challenged by Michael Bravo, who investigates the local networks in which La Pérouse’s informants in Japan were engaged, and by Tessa Morris-Suzuki, who advocated a “view from the region” that attempts to reconstruct the local population’s own reactions to European visitors. But none of these authors considered the Yoshishima island episode, which offers another perspective from three points of view: the importance of cartographic precedent, European awareness of cultural relativity, and the sacred network in which these islands participated. The emerging conclusion is that the standardization and centralization of modern science was accompanied by guesswork, negotiation and awareness of the flawed nature of the scientific endeavor.

The Yoshishima island episode is one model of a tentative encounter, where fragmentary contact was inconclusive: the appearance of an unusual “other” was explained in terms of each cultural group's knowledge system. In this case, the systems were doubly incompatible: both in terms of geography (topography versus topology) and in terms of worldviews (positivist versus sacred). La Pérouse was using a European map of Japan that he assumed reflected a territory accessible by ship and direct observation. That map, however, was based on the cartographic reproduction of the medieval imaginary of a sacred topology, strewn with marginal islands meant to safeguard the main islands of Japan. Paradoxically, La Pérouse was right in his erroneous attribution: the island he thought he saw (Yoshishima) fulfilled the same protective purpose as the island he actually saw (Hegura).

Radu Leca is an Assistant Professor in History and Theory of Art at the Academy of Visual Arts, Hong Kong Baptist University. Radu holds a BA in Japanese Literature at Kanazawa University, MA and PhD in art history at SOAS, with a thesis on the spatial imaginary of late 17th century Japan. Radu is currently editing a publication on the Sir Hugh and Lady Cortazzi Collection of Maps of Japan at the Sainsbury Institute of Japanese Arts and Cultures in Norwich, to be published next year. He was a MacLean Collection Map Fellow in 2018.

References

Aoyama, Hiro’o青山宏夫, Zenkindai chizu no kūkan to chi前近代地図の空間と知 (Tokyo: Azekura Shobō, 2007), 194-201.

Boxer, Charles, Jan Compagnie in Japan, 1600-1850 (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1936), 5-6.

Gaziello, Catherine, L'Expédition de Lapérouse 1785-1788, Réplique Française au Voyage de Cook (Paris: C.T.H.S., 1984), 22-23.

Gladwell, Malcolm, “Open Secrets: Enron, Intelligence, and the Perils of Too Much Information,” in What the Dog Saw and Other Adventures (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2009), 151-76.

Hashiguchi, Naotake, Mark Hudson and Mariko Yamagata, „The Izu Islands: Their Role in the Historical Development of Ancient Japan”, Asian Perspectives 33-1 (1994): 138-41.

La Pérouse, Jean-François de Galaup, The Journal of Jean-François de Galaup de la Pérouse, 1785-1788, vol. II, John Dunmore, ed. (London : The Hakluyt Society, 1995), 269-70.

Matsui Yōko 松井洋子, “A New Map of Japan and Its Acceptance in Europe,” in Wigen, Kären, Sugimoto Fumiko and Cary Karacas (eds.), Cartographic Japan – A History in Maps (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 41-3.

Milet Mureau, Louis Marie Antoine Destouff, ed., The Voyage of La Pérouse Round the World in the years 1785, 1786, 1787 and 1788 (London: John Stockdale, 1798), vol. 1: 25, vol. 2: 23-4.

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. “The Telescope and the Tinderbox: Rediscovering La Pérouse in the North Pacific.” East Asian History 39 (2014): 35-8.

Pelletier, Philippe. La Japonésie : Géopolitique et Géographie Historique de la Surinsularité au Japon (Paris: CNRS, 1997).

Pegg, Richard A. "Ceramic Cartography: Japanese Map Plates and the Tempo Era (1830-44)," Orientations, vol. 47, no. 5, June 2016, 69-76.

Siebold, Philipp Franz von, Geschichte der Entdeckungen im Seegebiet von Japan nebst

Erklärung des Atlas von Land- und Seekarten vom japanischen Reiche und dessen

Neben- und Schutzländern (Berlin/Leiden/Amsterdam, 1852), 136.

Taglioni, François, “Les petits espaces insulaires face à la variabilité de leur insularité et de leur statut politique,” Annales de géographie 652 (2006): 676-9, https://doi.org/10.3917/ag.652.0664

Ury, Marian (transl., ed.), Tales of Times Now Past: Sixty-Two Stories from a Medieval Japanese Collection (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1979): 159.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.