Though National Poetry Month has passed, May 8, 2023 marked 252 years since Phillis Wheatley’s departure from Boston Harbor on a journey to London that would result in the publication of Wheatley’s historic first volume of poetry in 1773, as well as her eventual emancipation from slavery a few months after her return. Understanding the history and geography represented in those 252 years, and understanding the life and poetry of Phillis Wheatley and the countless other poets which followed her, are two endeavors which complement each other strongly as we strive to understand our present world and the city around us. Poetry is, after all, a form of expression, one rooted in life and experience and the people and places which surround the poet and their work. I think especially when it comes to Boston, there is a rich and really valuable lineage of poetry as a cultural expression intimately entwined with the complexities of the city and its communities, a lineage which spans just about the whole of Boston’s history in time and in scope.

From Left: Poets Phillis Wheatley, Sylvia Plath (photograph by Giovanni Giovannetti/Grazia Neri), and Audre Lorde (photograph by Elsa Dorfman).

Where history and geography as academic fields offer a strict and rigorous analysis, I think this poetic lineage can offer a critically human and personal counterpoint. Poetry, as a projection of voice, can make heard and make felt what would otherwise be ignored or overlooked. In Boston’s dense and contradictory history, stretching from the horrors of American slavery to the privileged complacency of east coast academia and suburbia, and including both the harsh realities of socio-economic inequality and the community-based activism and solidarity which it sparks, there is always something to be gained from a closer look at the personal lives and diverse experiences of the countless people involved.

Most importantly, where the arts absorb, sample, and recombine influences from the past and the present in new and daring ways, they inspire and give voice to a possible future which I think is inherently vibrant and hopeful. I’ve collected a few figures who I’ve been inspired by, who wrote, lived, and expressed themselves in the landscapes and communities which I’m proud to inhabit or neighbor.

Phillis Wheatley

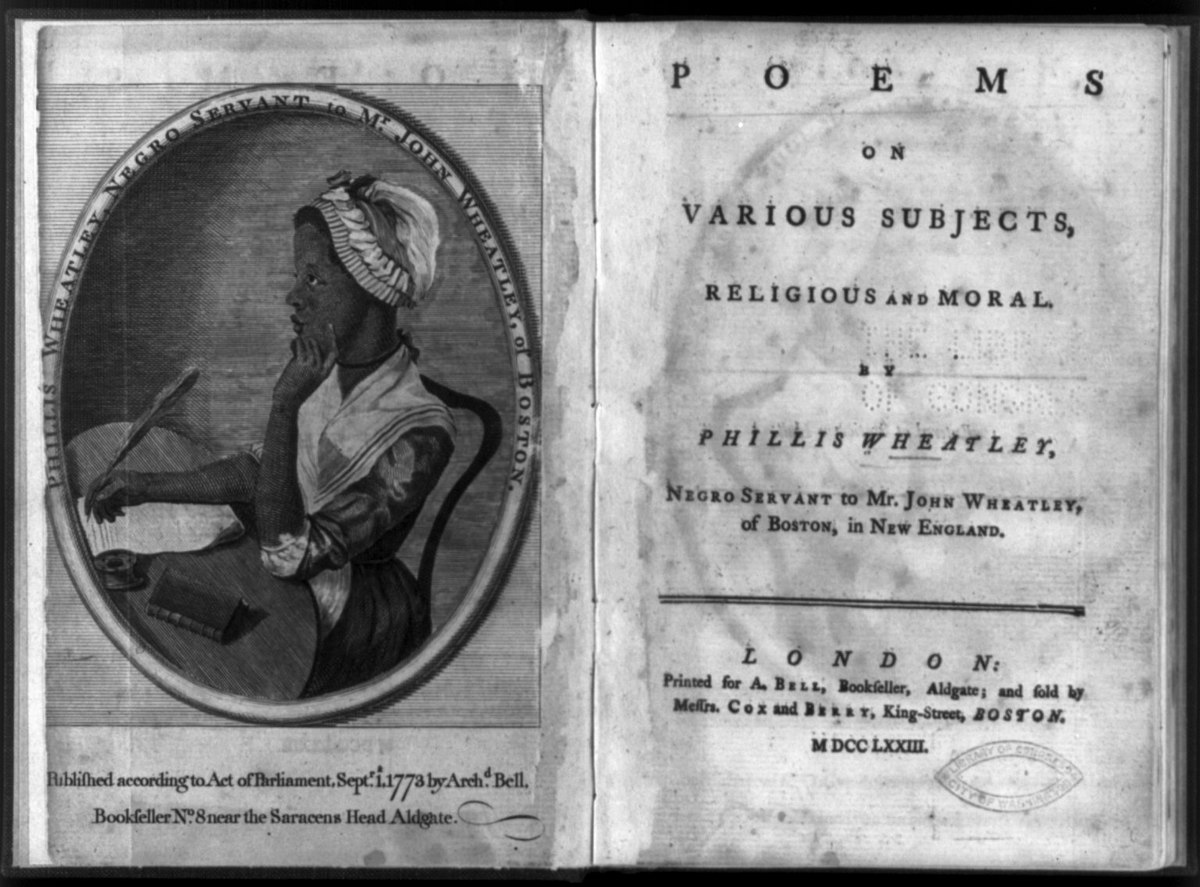

The frontispiece and title page of Phillis Wheatley’s first volume of poetry, "Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral" was published in London in 1773. Note the description of Wheatley as a "negro servant to Mr. John Wheatley of Boston in New England".

“…for in every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of freedom; it is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance” -Phillis Wheatley, 1774, “Letter to Samson Occom”

However thoroughly the study of history is conducted, the records and notes it accumulates, will never compare to the inspiration sparked when a look towards the past returns a face and a life to relate to. For Phillis Wheatley—born in Africa, subjected to the dehumanizing brutality of European slavery, and yet still making her voice heard and her humanity acknowledged—there was no one to look back towards. She was the first in so many ways: a woman of color who would achieve considerable fame in an otherwise oppressively white and patriarchal colonial society; the first person of African descent to publish a book in English, and only the third woman to be published in the colonies. Accomplishments she achieved at the age of nineteen, with no family or community to support her other than the white household which enslaved her.

The Wheatley mansion was located at the corner of State Street and Kilby Street, one city block away from the harbor and Long Wharf, and not far from Boston Common. Pictured here in a 1797 map of Boston

Laboring to understand the history around us we can begin to map out the life of Phillis Wheatley as it intersects with the city which was forced onto her life. From her arrival in Boston harbor as an orphaned and sickly child, to the Wheatley homestead in the heart of colonial Boston where she would not just learn the language of her oppressors (and Greek and Latin too) but master it, demonstrating an intellectual and artistic genius which was always critically aware of her position in a much wider colonial world.

This print (ca. 1855-1870) depicts Boston’s Old South Meeting House Church where Phillis Wheatley worshipped.

‘Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die.” Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

-On Being Brought from Africa to America, 1773

More than anything Wheatley’s life is a story of perseverance against the cruelties inseparable from American society and history. Though she wrote herself to freedom, receiving the acclaim of many of her contemporaries, life in early Boston’s free black communities was one where hardship and poverty were constant threats. Phillis Wheatley never ceased to critique white supremacy and the institution of slavery, and she never ceased to practice her voice and her craft, writing and attempting to publish a second volume of poetry even as the means to support herself and her family grew thinner. Her death in relative obscurity at the age of 31 while her husband was imprisoned on debt charges, and the subsequent loss of much of her writing and artistic legacy, is the tragic but unignorable conclusion to a life which is as inspirational as it is urgently relevant to the critical period of history which defined it.

Sylvia Plath

Sylvia Plath in London in 1961. Photograph by Giovanni Giovannetti/Grazia Neri

“My childhood landscape was not land but the end of the land—the cold, salt, running hills of the Atlantic.” -Sylvia Plath, 1962, “Ocean-1212-W”

I remember the first time I heard Sylvia Plath’s poetry, read by the poet herself in a recording of a 1962 BBC broadcast which especially highlighted the dynamic contrasts and almost brutal energy she managed to incorporate in her work. In a deliberately perfect and perfectly deliberate pronunciation, she delivered a language distinctly her own, which perfectly wielded the stylistic demands expected of her in her time, while also displaying an introspective intensity and an ability to represent and undermine which still feels strikingly contemporary.

The ocean surf along Winthrop, Massachusetts pictured here ca. 1917-1934.

…

Grey waves the stub-necked eiders ride.

A labor of love, and that labor lost.

Steadily the sea

Eats at Point Shirley. She died blessed,

And I come by

Bones, only bones, pawed and tossed,

A dog-faced sea.

The sun sinks under Boston, bloody red.

…

-Excerpt from Point Shirley, 1960

Plath’s life and career seem to form a trajectory which takes her steadily away from Boston. She was born in Jamaica Plain but moved across the bay to “the end of the land” (also known as the town of Winthrop) at the age of three, before moving to Wellesley in the outer suburbs at the age of eight. A gifted writer from an early age, Plath was first nationally published when she was 18, in Boston’s Christian Science Monitor. From there she would graduate from Smith College in western Massachusetts, before heading to the University of Cambridge on a Fulbright scholarship. The formal success of her career matches the unassuming formality of the landscapes and institutions she traversed, in contrast to the energetically passionate and boundary-breaking nature of the work she produced.

At the heart of this contrast are the expectations and demands placed on her as a female writer navigating the deeply sexist institutions of academia and publishing in the 1950s and 60s. The power with which Plath writes has the urgency of establishing a creative identity and voice which is honest and powerful despite the bigoted expectations and demands of her environment.

The violence and turmoil associated with her work is indicative of this personal struggle, but is matched by the lively and masterful use of her voice to reimagine and undermine the hostile forces surrounding her life. In her language, Sylvia Plath is undeniably alive; she broke many boundaries of silence around topics such as mental illness and domestic abuse, and did it as an artist defiantly confident in the power of her own voice.

Audre Lorde

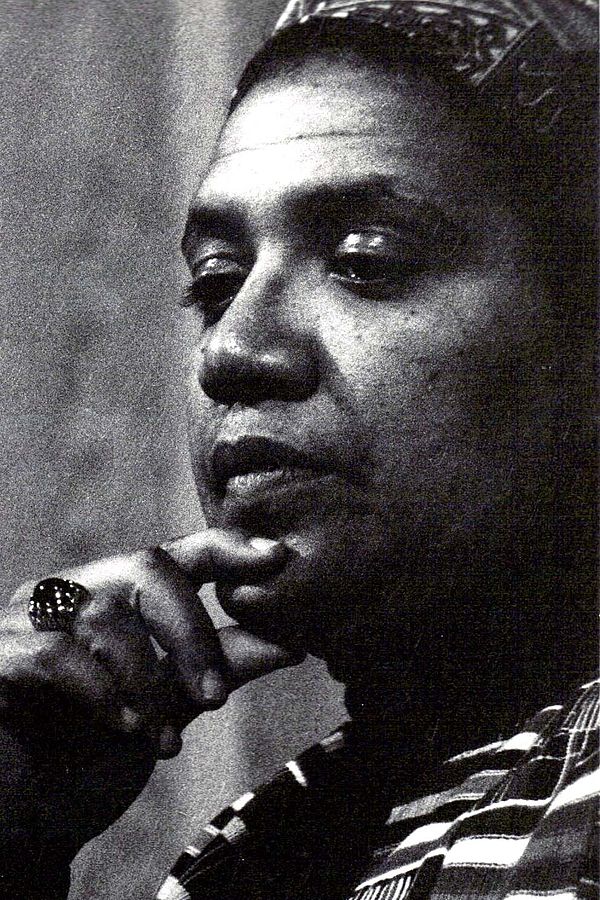

Audre Lorde in 1980. Photograph by K. Kendall.

“For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action.” -Audre Lorde, “Poetry is not a Luxury”, 1977

Audre Lorde, who described herself as a “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet,” defiantly paved the way for so much of our contemporary understanding of change and resistance to oppression through both her poetry and writing as a whole. In her life and work, I think more than anything there is a determination to wield language as power which acts on every level between the experiences and emotions of an individual and the conflicts and struggles of the wider community. For Lorde, language is a necessity in a struggle against oppression which spans all the different ways we define our identities and go about our lives. Which, crucially, is a personal and intimate struggle just as much as it is a matter of the larger movements and relations which fill history books.

Though Lorde was born and lived much of her life in New York City, her life and work crucially intersect with the communities of Boston through her participation in some equally pathbreaking organizations which were formed here in the 1970s and 80s.

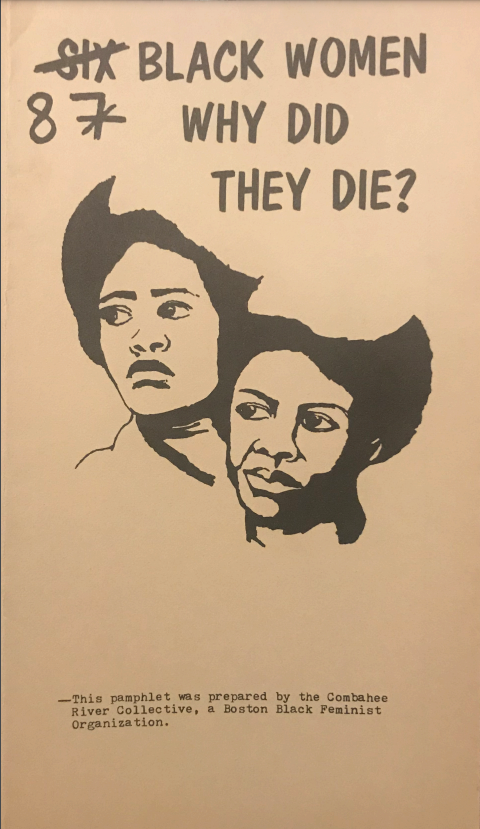

Combahee River Collective

In 1979 twelve women were murdered within a 2-mile radius in Roxbury, Dorchester, and the South End. The Combahee River Collective produced a series of pamphlets as the situation developed to raise awareness, provide resources, and analyze the situation in the context of the larger issue of violence against women in society. From the digital collections of The History Project: Documenting LGBTQ Boston.

“The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression…” -Combahee River Collective Statement, 1977

The Combahee River Collective (named after a Civil War raid led and organized by Harriet Tubman) was formed in 1974 by black feminist activists, scholars, and writers who were dissatisfied with prevailing feminist organizations—noting the sidelining of women of color in the predominantly white nation-wide feminist movement, and the sidelining of queer voices in the mainstream black feminist movement. The collective met in Boston and Cambridge until 1980 and was not just significant for the intellectual discourse and development it prompted—influencing and being influenced by the thought and poetry of members like Audre Lorde—but also for the very active role it played in community activism during a very tense and divisive period in Boston’s history.

Members of the collective were active in various political struggles regarding institutionalized racial segregation, organizing protests against instances of injustice and police brutality, and supporting initiatives to improve community resources and support. At a time when the economic deterioration of many of Boston’s urban communities was matched by considerable racial tension and violence stemming from desegregation efforts in the public school system, the efforts of the Combahee River Collective were a part of wider responses in otherwise marginalized communities.

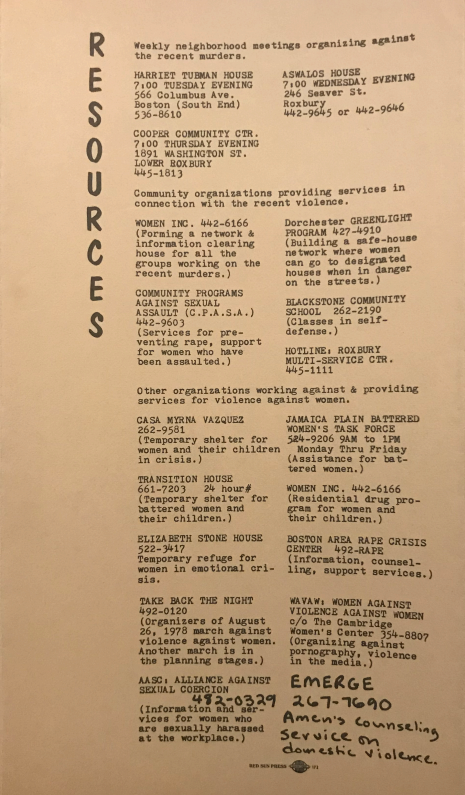

A list of resources included in the Combahee River Collective’s 1979 pamphlets which show the extent of the community response to the murders. Including weekly meetings, support networks, self-defense classes, as well as a list of local organizations working against violence against women. From the digital collections of The History Project: Documenting LGBTQ Boston.

“we find our origins in the historical reality of Afro-American women’s continuous life-and-death struggle for survival and liberation” -Combahee River Collective Statement, 1977

Historically significant institutions and organizations founded during this period include Transition House, founded in Cambridge in 1976 as the first domestic violence shelter on the east coast and the second in the country, Sojourner: The Women’s Forum, a feminist periodical also founded in Cambridge in 1975 and active until 2002, and Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, founded by members of the Combahee River Collective at Audre Lorde’s suggestion in 1980. The power of language, as expression and as argument, in the end always works towards the primary driving force of history, which is action at an individual and collective level, and the creation of resources and spaces where voices can be empowered, and diverse experiences considered.

The impact of Audre Lorde’s life, dedicated to empowerment and to change in a truly global and uncompromising way, and the history of resistance and survival in Boston which involves countless individuals and diverse communities, intersect in a relatively small but definitely inspirational way. A reminder of the power of our experiences and voices, each inseparable from the place we call home and the communities we cherish, and undeniably critical to their vibrancy and survival.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.