In August 2023, the Leventhal Center hired three Boston Public Schools students to use Atlascope to explore neighborhoods and write articles together about what they discovered. Their work featured here is connected to our recent Building Blocks exhibition, which focuses on a variety of stories which come from observations in the urban atlas collections.

Atlascope is a tool that helps explore the history of Boston by looking at how detailed maps of the city changed over time. Atlascope can be used to track building ownership, trace your own family ties in Boston, and learn about the history of the Greater Boston area. When we first began looking at Atlascope, it was apparent that the South End neighborhood had a history particularly worth exploring. The land area that the South End sits on was filled in beginning in the 1840s. After the landfill was completed, rows of townhouses and brownstones filled the streets of the neighborhood. As time went on, the South End was seen as less desirable compared to Back Bay, and the richer South End residents moved away. This meant that, relative to Back Bay, the South End was largely made up of lower income families and individuals. Later, the South End also became a safe haven for struggling artists. Since the late 1970s, however, gentrification drove out many immigrants and lower income residents. We picked the South End to explore via Atlascope because of how much the neighborhood has changed over time, and to think about the early histories that led up to the neighborhood’s present gentrification.

A 1960 map of the South End indicates areas that were “deteriorating,” “deteriorated,” and planned for renewal.

Using Atlascope, we collected data on changes in the South End, looking at maps from 1882–1938 and comparing them to maps from today. We then chose to focus on three case studies that we felt best represented the history of the neighborhood and the changes it has experienced. Each case study explores one or a few locations that were pivotal in the history of the South End and how these changes can be seen using Atlascope.

The first case study, “The Beginning of Gentrification in the South End,” looks at developments in housing in the South End through Atlascope. Focusing on the Cyclorama and other arts districts in the South End, this case study evaluates the changes these spaces brought to the neighborhood. There we could see the roots of the gentrification that would soon hit this community leading to a drastic change in the neighborhood.

The second case study, “The Lasting Impact of Settlement Houses in the South End,” focuses on the settlement houses that were established in the South End around the turn of the century. These institutions primarily served the growing immigrant populations of the neighborhood and provided them with housing, and social, economic, and recreational opportunities. We chose to tell the story of these organizations and the communities of the South End through three locations that were once owned and operated by the South End Settlement House. The diverging fates of these buildings provides an insight into what has changed in the South End and what has remained the same.

The third case study, “The Lost School of the South End,” discusses the history of the Girls’ High School, which was opened in 1852, and educated mostly young women before it was closed in 1974. The school educated many renowned women, and had a prestigious reputation for years. When it closed a lot of the history behind the school and its alumni faded, so we chose to bring their stories to light again.

The Beginning of Gentrification in the South End

by Winona Wardwell

Gentrification has become a significant, controversial issue in Boston. Many neighborhoods are now struggling to maintain the presence of residents that have lived there for decades while also trying to adapt to growing housing prices. The South End is no exception. Atlascope can take us back further in time to think about how the neighborhood has undergone major changes because of new developments.

When the land around Downtown and South Boston was originally filled in the mid-1800s, its purpose was to create homes within walking or streetcar distance of downtown Boston. Yet the South End struggled to attract the same elite residents as Back Bay, which was also filled around this time. As the wealthy flocked further to new, stylish parts of the city, open buildings in the South End attracted a whole new demographic of people from all over the world seeking jobs and cheap housing. Emigrants from Europe, the Middle East, and Africa moved there, in addition to people from other parts of the country like Black Americans from the South during the Great Migration. By the early twentieth century, the neighborhood had all types of food, religious buildings, and people. These people found jobs in the neighborhood, including at the surrounding lumber yards, furniture factories, and machine shops on Bristol Street, which is modern-day Paul Sullivan Way.

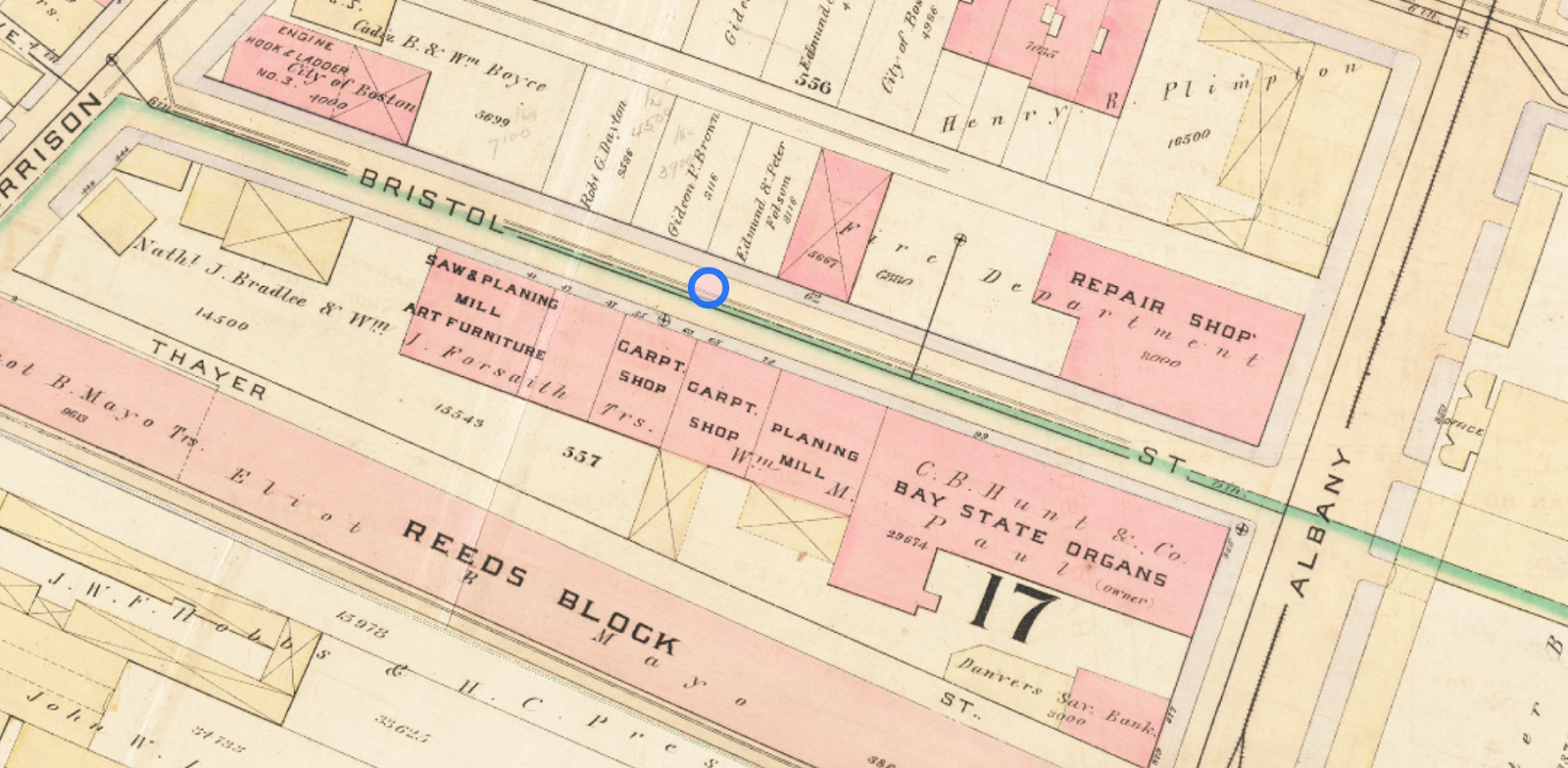

In 1888, Bristol Street was lined with factories and shops.

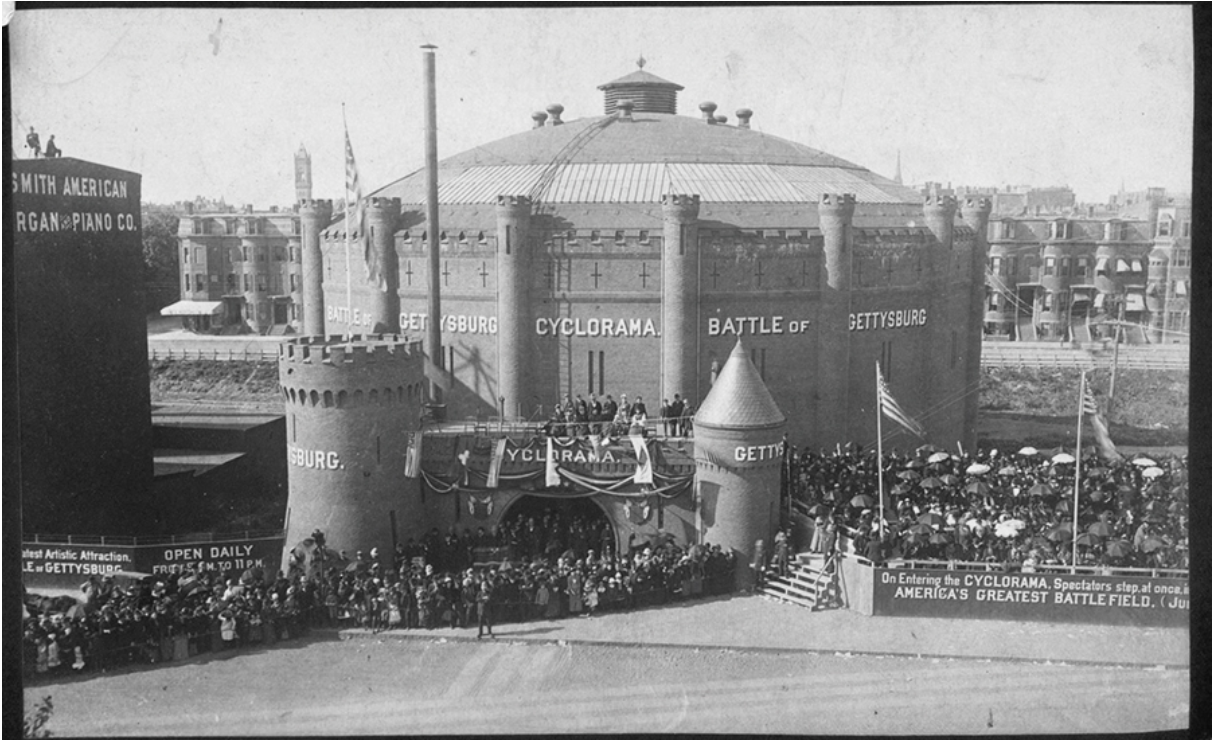

In the late 1800s, theaters, operas, and hotels started popping up in the neighborhood in places that used to be housing. One of the most unique of all of these recreational facilities was the Cyclorama, which made its debut in 1884 on Tremont Street. The Cyclorama is a large circular building created for a specific purpose: to hold French artist Paul Dominique Philippoteaux’s panoramic paintings of the Battle of Gettysburg from the Civil War. The opening of this building was monumental, and people flocked from all over the city to see these paintings that Philippoteaux had spent years on.

The grand opening of the Cyclorama was held on December 22, 1884.

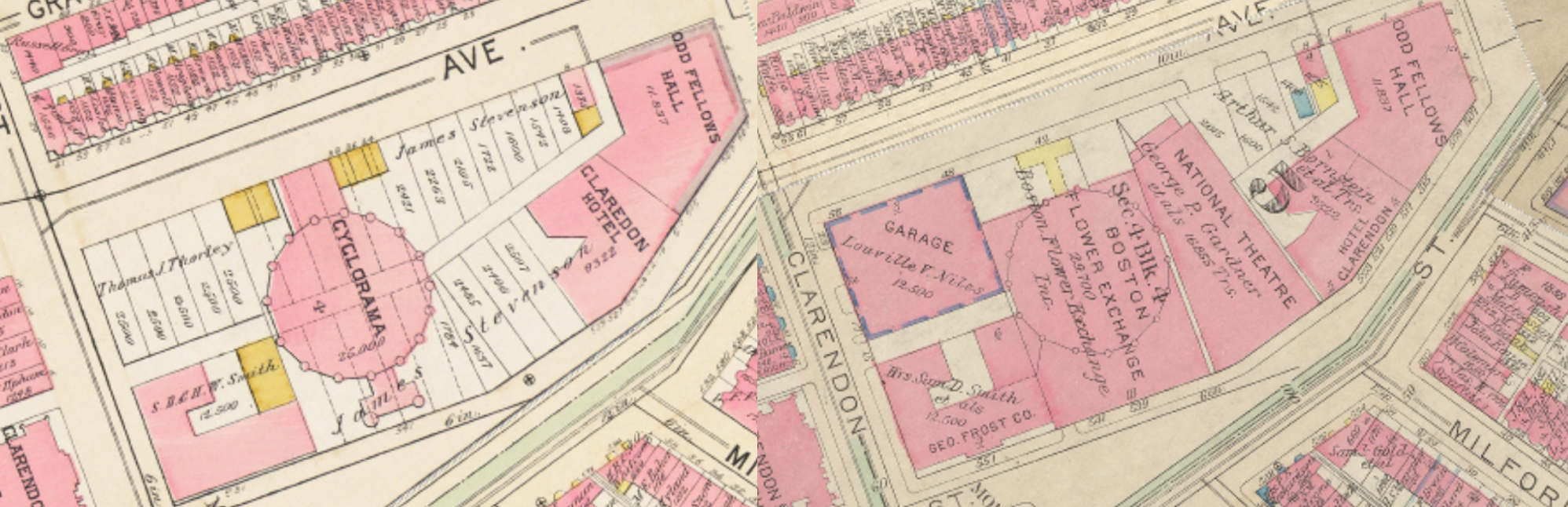

After the paintings moved to Philadelphia in 1891 (and eventually to the Gettysburg National Military Park), the Cyclorama housed all types of entertainment for Bostonians—from paintings of Hawaiian volcanoes to boxing events in the early 1900s. Then the Cyclorama became a flower exchange, before being bought by the Boston Arts Center in 1971. As wealthier people came into South End, they brought more expensive businesses with them, raising prices in the community.

Here one can see changes around the Cyclorama. In 1888, there were a variety of small buildings used for apartments and factories. By 1912, the block had filled in with larger buildings like theaters and hotels.

Similarly, on Ashland Place from 1870 to 1902, there was a similar pattern of housing becoming theaters and operas

After the Great Depression and both World Wars, the neighborhood fell into disrepair, and became the target for new development from private companies as well as government-led initiatives. By the 1960s, wealthy people had taken over the once utilitarian factories and turned them into industrial modern apartments. Soon the South End was one of the richest parts of Boston, and the people who had once lived there had fled all over Greater Boston. Memories of the former community can still be seen in the architecture, as the bones of the large factories still remain, despite the purpose of the building being different. For example, Washington Street, where theaters used to be, now features affordable housing for artists. This housing offers people a chance to stay in their community and preserve some of the culture. Still, looking at the neighborhood, it is hardly a window into the culture that once flourished in this community.

Winona Windell is a senior at Boston Latin Academy. She lives in Jamaica Plain, and for fun she likes to read, play piano and row. In the future, Winona would like to study political science and environmental studies.

The Lasting Impact of Settlement Houses in the South End

by Clare Ablett

While the South End was built with the intention of being a neighborhood for the wealthy, that has not always been the case. Many of the brownstones and row houses look the same on the outside from when they were built in the mid-nineteenth century, but their purposes and the people they house have changed drastically. After the Great Fire of 1872 and the financial panic of 1873, many wealthy residents left the South End for the newly-built Back Bay. This turned the neighborhood into an opportunity for new immigrants from all over the world to move to.

In an effort to both serve these immigrant populations and encourage their assimilation, settlement houses began to form. The first one created in the South End was the South End House in 1891 by Robert Archey Woods and William J. Tucker. Woods was inspired to start the house after visiting the first settlement house, Toynbee Hall, in London. It was initially called the Andover House, as Woods was a graduate of Andover Theological School, where Tucker taught. Andover House had a location at 6 Rollins Street. This house was meant to serve as a residence for immigrants, but the organization quickly expanded to provide many more services and with this expansion it acquired several more locations. Looking back, the former properties of the South End House provide an insight into the ways that South End has changed over the years and the variety of populations that it continues to be home to today.

In 1902, the South End House headquarters were located at 20 Union Park.

In 1901, the headquarters of the South End House moved from its original location on Rollins St. to 20 Union Park. Union Park is one of the most beautiful streets in the South End and after it was built in the mid 1800s, it quickly became home to many wealthy and socially prominent people including Governor Alexander Hamilton Rice. The movement of the settlement house headquarters and the rise of many lodging houses along the street displays how the neighborhood was changing in the early twentieth century.

Union Park in a 1938 photograph

What was once a home for the wealthy was now a place serving immigrants, a group of people that was not included in the initial vision for the neighborhood. The South End House, and later the United South End Settlements, continued to operate out of its Union Park headquarters through the 1960s. During this time it served as a pivotal location in the movement to stop the demolition of houses as part of urban renewal in the South End by the City of Boston, with the sit down strike for a “United South End” being held there in 1968. However, the historical significance of this place and the role it played in the shaping of the South End has seemingly been forgotten. Union Park was one of the first streets to gentrify in the early 1970s, as many working class residents were replaced by wealthier professionals. 20 Union Park is no longer a settlement house or a library or a bustling center of civic engagement. It has been turned into expensive condos.

The property at 171 West Brookline Street was owned and operated by the South End House from 1907 to the mid 1920s as a room registry and women’s club.

The former room registry and boarding club of the South End House has also met a similar fate as 20 Union Park. 171 West Brookline Street was owned and operated by the South End House from 1907 until the mid 1920s. It served as a place where people, particularly women, could socialize and find a place to stay in one of the boarding houses that the South End House operated. However, unlike 20 Union Park, the West Brookline property was sold by 1928 to a private owner and has continued to be in private ownership since. Today, this place where immigrants could come for a place to stay as they adjusted to life in a new country is a single family home worth over $4 million. Both Union Park and West Brookline are symbols of a changing South End; a place that was built for the wealthy and turned into a haven for immigrants before becoming a neighborhood that is increasingly difficult to afford for many Bostonians.

Not all of the settlement house properties have followed the same paths as the Union Park and West Brookline St. locations. In fact, others have met completely opposite fates. As the South End House grew, it opened a residence in 1913 specifically for women on East Canton Street.

In 1913, the South End House expanded and opened a residence specifically for women at 43-45 East Canton Street.

This was a place where single and working women could live and access services and resources. It was essential in a society that had limited opportunities for these women. Now, this residence building no longer exists. It stood during a time when East Canton Street crossed Harrison Avenue on the block between Harrison Avenue and Mystic Street. In 1920, the residence closed and by 1949 this street no longer existed, it was now the location of the Cathedral Apartments Public Housing Development (now the Ruth Lillian Barkley Apartments). While the building itself no longer stands, the purpose for which it was built is still being carried out on that plot of land. It still serves as housing designed not for the wealthy elites, but for people who are the backbone of Boston and historically of the South End as well.

The United South End Settlement 1978 Annual Report details 10 human service programs, one training program, three planning grants for neighborhood revitalization and community development, and a year-round camp in New Hampshire.

The settlement houses of the South End were created out of need to serve new communities that were forming in the neighborhood, but they became so much more than that. The institutions that started with the goal of providing housing for a few people turned into trusted organizations that provided health care, recreational opportunities, social clubs, and centers of community-based activism for thousands. While it was the oldest, the South End House was far from the only settlement house in the area. The Harriet Tubman House, the Lincoln House, the Hale House, and others were all operating as valuable centers of service and community during the same time. All of these organizations eventually merged in 1959 and became the United South End Settlements (USES). Despite the changing purposes of many of the original properties of the settlement houses, USES continues to serve low-income families in the South End and “break the generational cycle of poverty.”

The story of the South End is a complicated one. It is a place that has experienced incredible waves of wealth and poverty over its history. Now as it becomes one of the areas hardest hit by gentrification, it is vital that its history as an immigrant neighborhood is not forgotten or ignored. Even while these buildings may no longer stand or serve these purposes, they still must be remembered for their lasting impacts on each person they served and on the larger community of the South End.

Clare Ablett is a senior at Boston Latin Academy. She lives in Dorchester and enjoys music, rock climbing, and reading. She hopes to study anthropology and creative writing in the future.

Lost School of the South End

by Bridget Hurley

The Girls’ High and Normal School was opened in 1852, on the top floor of a library on Mason Street, to educate young women to be primary school teachers. The overwhelming influx of interest in attending forced the school to construct a new building on 75 West Newton Street in 1869.

In 1869, a new building was built at 75 West Newton Street to house the Girls’ High and Normal School.

The school was in a state of constant change; in 1876, the Normal School, the school for younger grades, split from the High School and moved to a new campus. The High School remained on W. Newton Street. Then, the High School began sharing facilities with Girls’ Latin School (now Boston Latin Academy).

The new building at 75 Newton Street was designed to accommodate roughly 1,000 students. The facilities included 8 classrooms, 15 recitation rooms, 3 studios, 1 hall, and laboratories for chemical, physical, and botanical science.

From 1876 to 1885, many advancements to the school were made such as improved lunches, better ventilation, rearranging seating to provide better illumination, and fire drills. The Girls’ High School’s reputation grew as the city did. With the annexation of new neighborhoods such as Roxbury (1868), Brighton, Charlestown, Dorchester, and West Roxbury (all 1874), the school became known as one of the most prestigious girls’ schools in the area, and got the reputation for being the “the chief source of supply of teachers for the Boston schools."

A second year class engages in a zoology laboratory exercise in this photograph from 1893.

By the mid 1870s, the school had reached its full potential of engaging young girls and preparing them for their lives, in both the workforce and at home. The only thing that was missing was the same college preparatory curriculum that most boys in school had. So, in 1878, the Girls’ High School and the Girls’ Latin School started to increase their shared facilities. This step was taken because the Girls’ Latin School followed the same course of study as Boston Latin School. Although the schools had different leadership, the combination of schools was described as the largest high school in New England, with nearly 800 young women 14 to 22 years old, and a variety of courses offered like Latin, French, German, and English.

Despite how well things seemed to be going at this point, in 1903, the Boston Globe described the space as “insufficient.” To fix this issue, the Latin School moved to a building in Fenway. In addition, the mass waves of immigration that occurred in the early twentieth century also affected the Girls’ High School. At the same time, the school diversified, with students representing over 25 different nationalities. Throughout the 1920s the school was referred to as “the pride of Boston” and frequently praised. However, overcrowding made the buildings cramped and difficult to learn in.

In 1902, the Girls’ High School shared facilities with the Girls’ Latin School. Due to overcrowding, however, the Latin School moved to a different facility in 1903.

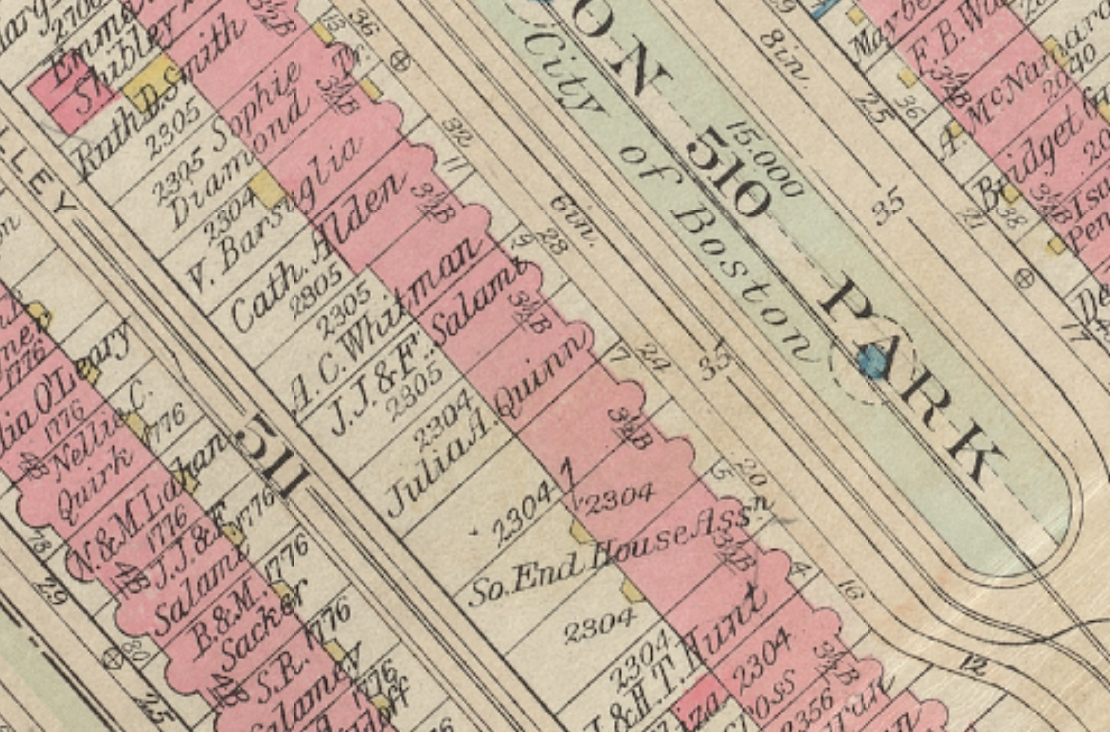

The school was closed by the City of Boston in 1974, and the building was demolished after that. In 1986, a park was built on that land. I chose this school to write about because I thought it was interesting how quickly this renowned school was demolished. It was considered to be one of the best places for young women to further educate themselves, and the city decided to permanently close it and make the land a park.

Many outstanding women attended this school, including Melnea Cass, activist; Ruth Roman, actress; Lillian A. Lewis, the first black female journalist in Boston; and Marcella Boveri, the first woman to ever graduate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Instead of demolishing the building, I think that they should’ve created a museum, highlighting the school’s achievements and the achievements of the alumni. The fact that instead of preserving the history of the school, they destroyed it, reflects what was going on in the South End in this period. The neighborhood of the South End had become more inhabited by the working class, which unfortunately brought more crime and danger to the neighborhood, mostly due to the lack of investment by the City of Boston and the increased poverty.

In 1986, O’Day Playground was built on the old site of the Girls’ High and Normal School.

It’s a shame that the Girls’ High and Normal School was closed and not preserved at all. Other schools that had similar statuses at the time are now still open. Why couldn’t the Girls’ High and Normal School be listed amongst Boston Latin, Latin Academy, or O’Bryant? Or, why wasn’t the history of the school taught to more people? It’s only since I recently started using Atlascope that I discovered this treasure lost in history. Viewing old maps is a great way to see how cities change, and how common that change was in the South End. The neighborhood went through many changes in its short history, starting when the land in that area was filled, in 1849, to now. The South End neighborhood is just so enriched with history that the less protected things are easily lost. The Girls’ High and Normal School was at one time a great place for young women, and now that it’s gone, it’s important to focus on preserving the memory so the incredible history of these young women in Boston doesn’t fade. You can still donate to the school’s Alumni Program.

Bridget Hurley is a sophomore at Boston Latin Academy. She has a twin brother and lives in Hyde Park. She likes to bake, hang out with her friends, and to run.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.