For our new rotating exhibition, Building Blocks: Boston Stories from Urban Atlases, the Leventhal Center hired and worked with three high school students from Boston Public Schools as teen curators. We asked them to choose a place in the city and explore that site’s history going back to the nineteenth century, using our urban atlas collection to kick off their research. We wanted them to consider how things change and how the present came to be the way it is today. Below, we’ve excerpted from their written research.

Maleeha Wasim: Hathaway Mansion

Senior at the John D. O’Bryant High School in Roxbury

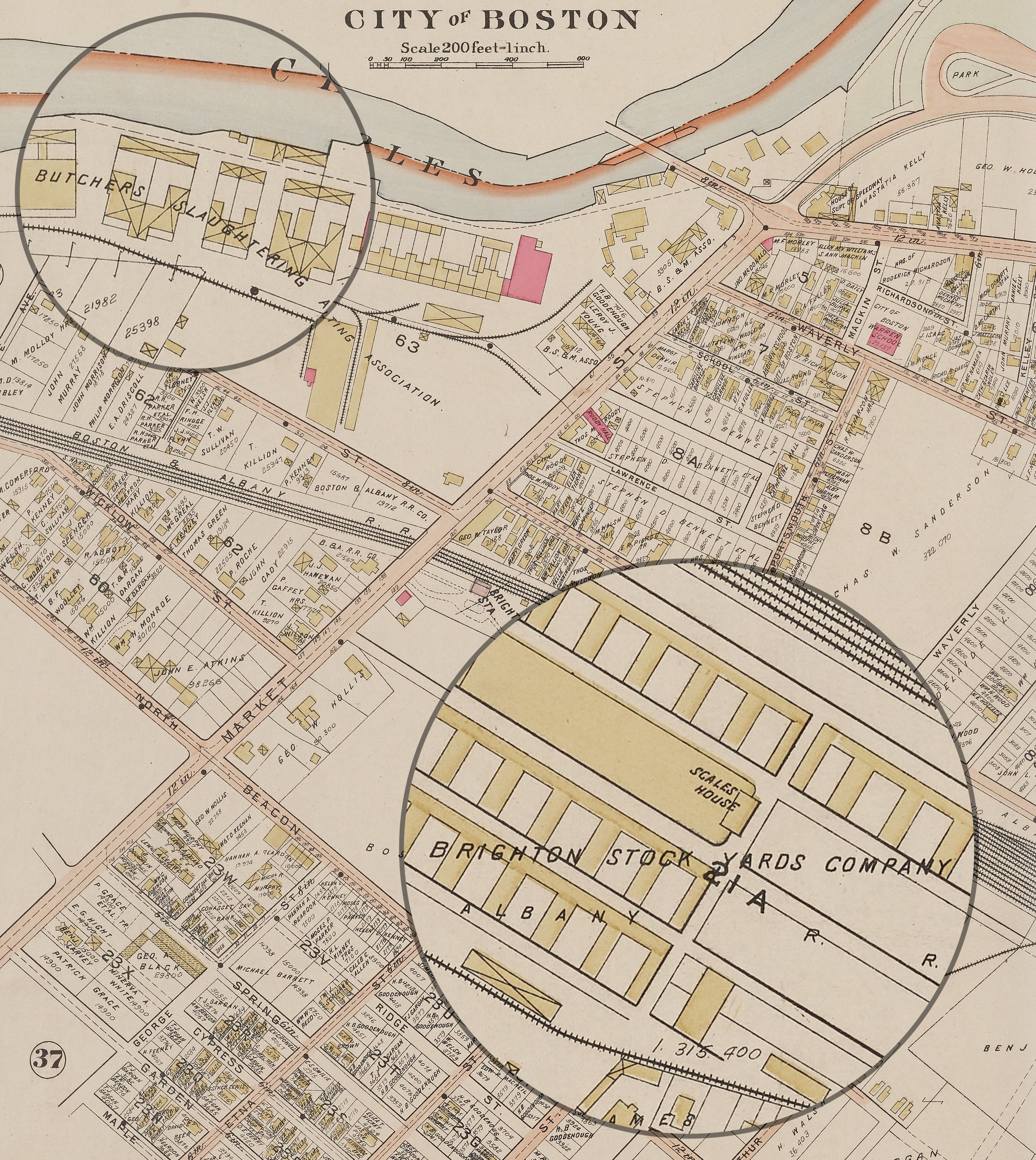

To the east of Market Street were the stockyards and to the west was the Abattoir, a site where cattle were processed and slaughtered.

Close to my home in Brighton, there’s an old-looking mansion off Academy Hill Road. I have wondered how the house is still standing, and why it looks the way it does. By searching for the house on Atlascope, I learned that James Ambrose Hathaway owned the property and it is known as the Hathaway Mansion.

Hathaway settled in Brighton around 1859 and made his fortune by exporting cattle to Great Britain. In fact, down the street from the Hathaway Mansion is Market Street, where cattle were brought into Brighton by the trainload on the Boston and Albany Railroad.

The expansion of the Boston and Albany Railroad allowed the cattle industry to advance significantly by the time Hathaway arrived. The slaughterhouses and Abattoir, built in 1870, became a profitable industry for many property owners who were involved in the cattle business. Profits from the cattle trade also advanced real estate markets.

By the 1820s, between 2,000 and 8,000 heads of cattle were delivered to the Brighton Cattle Market each week. On Thursday mornings, hundreds of farmers and merchants parked their vehicles in front of the Cattle Fair Hotel, eager to buy sheep and cattle. Farmers throughout the U.S. and Canada knew about the Market, which sold hundreds of thousands of cattle each year for over two million dollars in sales. Butchering and selling cattle was economically profitable and influenced Brighton’s growth, transforming Brighton over time from a simple agricultural village into a prosperous “animal suburb.”

Interpretations: Our Relationship to Animals and Food

It’s amazing how an old mansion led me to learning about a thriving cattle sector in historic Brighton. It impacted local families and individuals and influenced the town’s political and economic affairs. And it attracted a lot of tourists, commerce, and animals via railroads. Just as Brighton’s past connection to the bustling cattle market is now often forgotten, so do we no longer have the close relationship with animals that we once did, or care how cattle are mechanically slaughtered and processed. Today, although we have more safety regulations that keep the slaughter factories in order, meat processing is kept behind closed doors, out of sight from the public. Could the story of Brighton’s stockyards help current and future generations care about how animals become food?

Nadia Madaoui: Kelleher Rose Garden

Senior at the John D. O’Bryant High School in Roxbury

I was born in Boston and I lived across from the Museum of Fine Arts for the first half of my life. During the warmer months of the year, my father or mother would take me and my brother to various spots around Fenway to pass time, whether that be flying little toy drones in an empty basketball court or riding bikes on a track. When thinking about where to focus my research, one spot that came to me in particular was the Fenway Rose Garden.

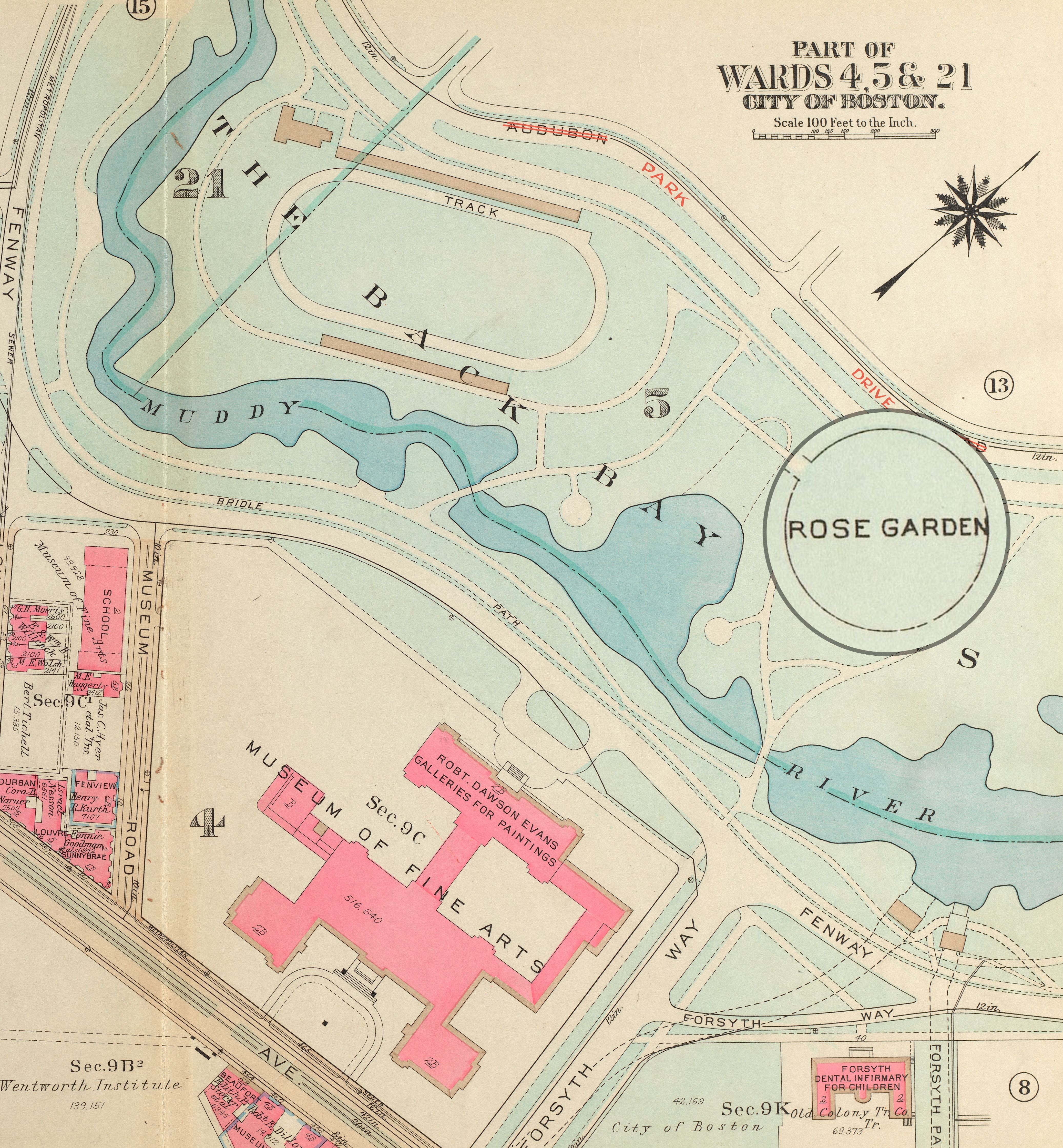

The Rose Garden is labelled on this 1931 atlas of the Back Bay Fens.

Well after land reclamation of Back Bay was complete in the late nineteenth century, Mayor of Boston James M. Curley implemented a plan to smooth the slopes in front of the Museum of Fine Arts and create a garden that would lighten the space. Built in 1931 and expanded in 1933, the James P. Kelleher Rose Garden is a site where visitors can come and rest and admire the many roses. It was and continues to be a place of peace for all those who seek it.

Memorials to Boston soldiers, those lost in the Korean, Vietnam and Second World Wars, are placed near to the Rose Garden. The largest, most decorated one of all commemorates those who lost their lives in World War II; it consists of a woman with wings spread wide holding a sword and a bundle of branches. I see this statue as guarding the honor of those who died or bringing peace to war.

The memorials speak of war not only in terms of victory but of loss. Even inside the Rose Garden wartime echoes. Along the gravel path you will find small signs with the names of the roes that grow there, many reminiscent of war or patriotism (Mr. Lincoln, Fourth of July, Veteran’s Honor).

At one end of the garden at the end of a long patch of green sits a white statue of a woman in grief, far from the embrace of roses. A green patina hangs in the crooks of her drapes. She mourns the loss of something beautiful. The statue is named Desconsol, which is Catalán for desolation. The statue is a replica of Josep Llimona’s original in Barcelona.

Interpretations: Rest in the Garden

Just as Desconsol is in mournful isolation, so are we. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has made more than 10 million people flee in refuge. And the war has affected all of us, from the economy to social relations. On top of that, we are still recovering from the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. The stress of this time in history has greatly affected students in high school. We too need places to rest. The Kelleher Rose Garden has lived through times of war and tension. People have found peace here, and you may too.

Anh Do: Ronan Park

Graduate of the Jeremiah E. Burke High School in Dorchester, current freshman at Northeastern University

Ronan Park in Dorchester is a place where people come to relax, get some fresh air and exercise. I often hang out there with my friend in our free time. We usually sit on top of the hill and look out at the beach or watch the trains and people that jog by. The park is one of my top choices to relax my mind. A lot of trees surround the park and walkways. I frequently sit under one of them and gaze out at the views.

Ronan Park appears in urban atlases around 1918.

When I looked at the maps of the area from the 1800s, I noticed that it wasn’t always a park, and there were multiple land owners that had the same last name Pierce. I wanted to learn why some of the Pierces didn’t build much on their lands.

The story of the Pierce family starts with John F. Pierce, who built two houses between 1818 and 1831 along the southeast slope of Mount Ida, the same hill on Adams Street that shapes Ronan Park. In 1846, his son, Charles Bates Pierce, married a woman named Mary Lyman Emery; they had two children, Elizabeth (b. 1847) and Charles Jr. (b. 1851).

In 1857, Charles Sr. died of typhoid, and he didn’t leave a will. Mary sold Charles’s properties and was listed in the 1860 Census as head of household with $7,000 in property and real estate. She was never actually able to access any proceeds from the estate, however. Instead, she had to petition for an allowance and was awarded only $355, forcing her and the children to live in a boarding house south of Fields Corner with twenty other people. When Mary’s father-in-law John F. Pierce died in 1871, his estate was split between various family members, including Mary’s son Charles Jr. and her daughter Elizabeth. Eventually, Mary managed to purchase the 151 Adams Street property from her son and other heirs.

Interpretations: The Complexity of Family

Family is a bridge that brings lives together. Mary went from living with her husband whose family were wealthy landowners to living in a boarding house with no support. In the Pierce family, they didn’t give Mary all she deserved, but she still gave what she had to others. In Mary’s story of family, there was brokenness. Through these experiences, however, Mary showed strength through generosity.

In my opinion, family can be as soft as talc or as strong as graphene. Expectations and hopes were high when my family moved from Vietnam to the U.S., simply because my parents wanted me to have a better education. My siblings were left behind with no clue when we’d be back. Being an immigrant in a foreign country, I had a hard time learning English and supporting my parents, but my family gives me the opportunities to grow and learn, and I will give back all I have.

For more from Building Blocks, please visit our digital exhibition.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.