Prospectors bound for the Klondike gold fields, in Chilkoot Pass, Alaska, 1898. Digital Commonwealth.

On August 16, 1896, three men discovered gold nuggets in the river while camping and fishing near Rabbit Creek in the Klondike River territory: American prospector George Carmack, and two Tagish people, Keish (Skookum Jim), who was Carmack’s brother-in-law, and Káa Goox (Dawson Charlie). It’s unclear which man made the discovery of the gold nuggets; most historians believe that Skookum Jim spotted it first, but that Carmack was named as the “official” finder, as the men feared authorities would not recognize an indigenous claimant.

The men staked their claim on that plot of land the following day. News of the gold strike spread fast across Canada and the United States; Rabbit Creek was renamed Bonanza Creek, and even more gold was discovered in a nearby Klondike tributary named Eldorado. The last great gold rush of the American West had begun: the Great Klondike Gold Rush. The rush would bring an estimated 100,000 prospectors to the Klondike region between 1896 and 1899, and had a profound impact on land, economic development, and native communities.

Maps, of course, have always played a role in the exploration of new lands. Both of our most recent exhibitions, Bending Lines and America Transformed, emphasize how maps have long been used not only as a tool to claim territory, but also to find and exploit resources, attain wealth, and even gain control of people.

Economics, Transportation, Advertising

“Klondike Fever” reached its height in the United States in mid-July 1897. Thousands of eager, ordinary people made their way north in search of gold. For everyday folks, the gold rush was a chance to turn their lives around; the potential discovery of gold promised a better life for families plagued by financial insecurity and recovering from the Panic of 1893 and Panic of 1896.

“The Gold and Coalfields of Alaska” map from the U.S. Geological Survey in 1898 shows deposits of resources (both gold and coal in this case), as well as steamer routes and trails.

For the national economy, too, the rush was an opportunity. The U.S. was in the midst of an economic recession with high unemployment levels, and the economy benefited both from the spending and innovation during the gold rush. Gold fever spurred spending on infrastructure such as railways, steamships and dams; on supplies, goods, and mining machinery, as individuals who didn’t strike it rich sold their stakes to mining companies; and on the rapid development of boom towns like Dawson City, where some rich prospectors spent their earnings on lavish lifestyles and entertainment.

The rush also led to the development and use of newly constructed railway and steamship routes, with railroads and steamer companies competing for travelers. A newly constructed Yukon Route Railway, built in 1899, cost 25 cents per mile, and was estimated at the time to be the most expensive train in the world. Both the federal government and private companies were doing everything they could to promote the Yukon territory as a land of opportunity, and maps were an important tool to announce these speculative advertisements. As we discuss in our Bending Lines exhibition, companies throughout time have used maps to advertise products, lure in financial investment, and gain customers and consumers, just as these examples do.

George Washington Bacon’s map of the Klondike shows routes to get to Klondike gold fields, including steamships, railroads, and projected railways currently under construction.

These maps all show detailed routes to get people and mining companies into the territory and to the gold deposits, but also to move gold and other resources out of it. And it wasn’t only the United States which was interested in capitalizing off the gold rush. Competing economic powers also scrambled to lay claim on the riches. One of the Klondike maps in our collection, “Philips’ sketch map of the Klondike gold region,” was created at the height of the Gold Rush in 1898 by mapmaker George Philip & Son, based in London, and uses information compiled by the “Klondyke Parent Pioneer Corporation,” a London-based investment company.

Philip’s sketch map shows rates of travel from Liverpool to various locations in the Klondike territory, as well as a diagram showing the basics of staking a claim.

Philip’s sketch not only lists travel routes, but also a table of distances, tips for the best season to travel, a detailed diagram with instructions on staking a claim, and a list of complete travel rates—Saloon and First Class, Second Cabin, and Steerage—with all rates calculated from Liverpool.

Scholarly research suggests that the influx of miners to the Yukon region created anxieties among Canadian officials over their possession of parts of the Yukon territory, as they expected economic and territorial threats from the United States. In 1898, a man named William Ogilvie, the Canadian Dominions Surveyor and Commissioner of the Yukon, traveled to Great Britain in an effort to mitigate these fears, by tying Canada more closely to the British Empire, creating economic links across the Atlantic, and marketing the Yukon gold fields to British investors, all as an attempt to ward off American influence.

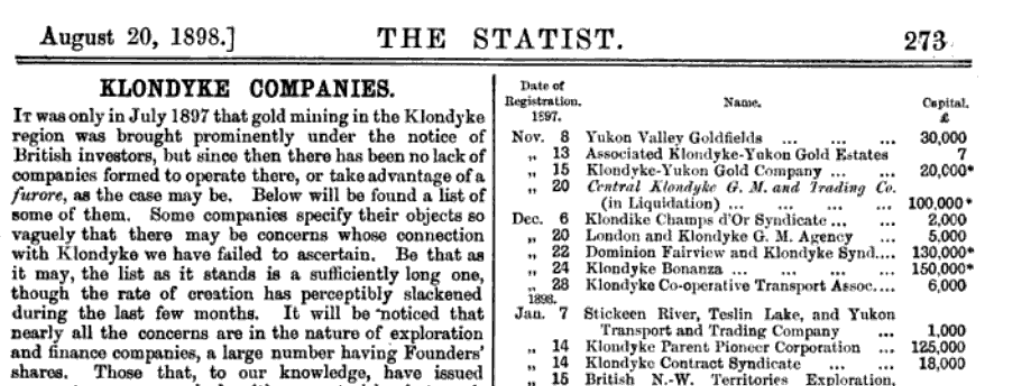

The Statist, a late 19th century British magazine, wrote in an August 1898 article that in July of 1897, “gold mining in the Klondyke region was brought prominently under the notice of British investors,” and that companies quickly formed to “take advantage of the furore" that was taking place in both individuals and mining companies on both sides of the Atlantic.

In this excerpt from The Statist, the Klondyke Parent Pioneer Corp. is listed near the bottom on the right hand side list of investment companies, with its capital listed at £125,000.

Native Peoples and Land Dispossession

Throughout the colonial world, the historical pattern of conquering land and scrambling for wealth and resources has often lead to the dispossession of native peoples. Our Leventhal Center educators teach many lessons about land upheaval and native presence, settler colonialism, and land dispossession throughout American history.

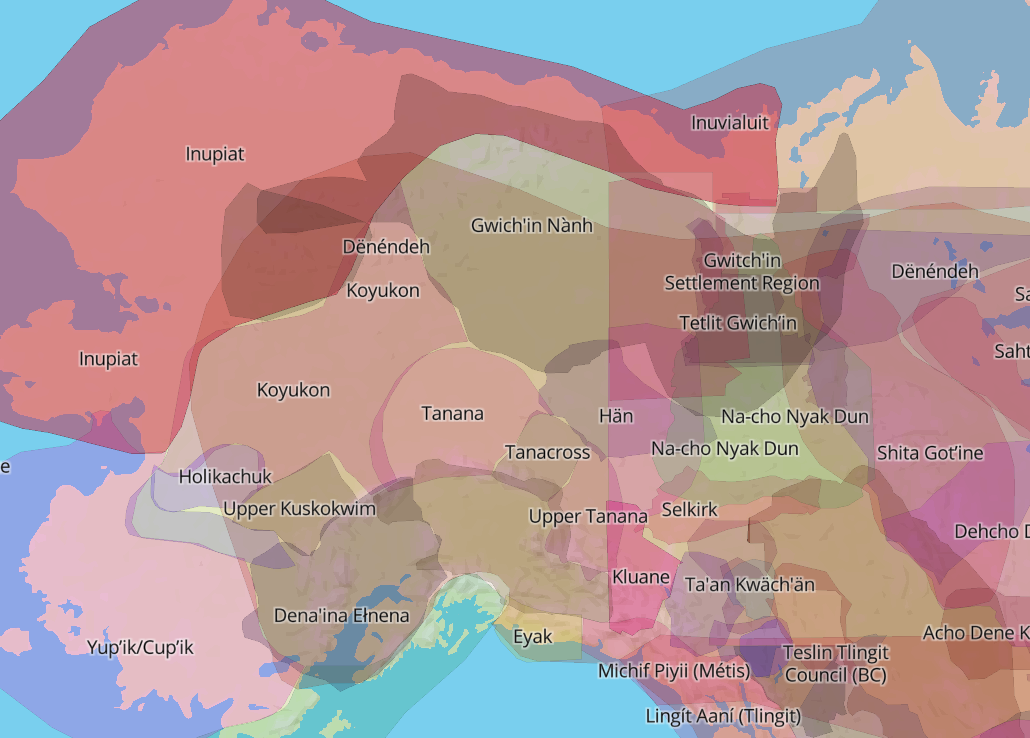

This Native Land Map shows Indigenous territories and languages across the world. In this image, you can see the traditional Hän lands in the center, encompassing the Yukon territory across the border of Alaska and Canada.

What did the Klondike gold rush and the development of the mining industry mean for the original inhabitants of the territory? In this region, indigenous groups such as the Hän people, semi-nomadic hunters and fishermen, suffered directly as a result of the massive influx of white propsectors and settlers, facing dispossession, disenfranchisement, and marginalization.

The Hän were forcibly moved out of their traditional hunting grounds and into a reserve to make way for the prospectors, who exploited the land by cutting down much of the timber and leaving the land’s former inhabitants without resources and stricken by poverty.

The End of the Rush

By the end of 1898, there was a mass exodus from the Yukon territory, and America’s last gold rush was over. Carmack and his family became rich off his initial discovery, leaving the Yukon with $1 million worth of gold, but most other individuals left with nothing. Large-scale gold mining in the Yukon Territory didn’t end until 1966, and today some small gold mines still operate there.

Like previous gold booms of the West, the Klondike rush ended almost as quickly as it began, and these maps remain relics of a short-lived moment of mass migration and individual opportunity, but also the longer-term stories of aggressive economic competition, questions of land and resource exploitation, and the challenging legacy of the displacement and abuse of indigenous populations.

*This article was updated on November 30, 2021 to reflect that the Klondike gold rush ended in 1898, not 1899. Thanks to our keen-eyed reader MJ Kirchhoff from Juneau who pointed out that data from two censuses shows rapid population decline in Dawson by the end of 1898, signaling the end of the rush.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.