This article digs into a case study from our latest Digital Commonwealth primary source set, Activism in Boston Over Time. In the set, you will find a collection of maps, photographs, film, and documents that reveal change over time in different Boston neighborhoods and the role of activism in driving those changes. You can also find a lesson plan for students in grades 8–12 that incorporates many of these sources as well as several others.

The Metropolitan Master Highway Plan of 1948

In 1948, the Massachusetts Department of Public Works released the Metropolitan Master Highway Plan, a “ten-year construction program for the relief of traffic congestion” detailing “a network of expressways of latest modern design and of sufficient capacity.” Included in the 204-page report are cost estimates, economic justifications, traffic tables, and maps of proposed expressways, construction stages, and more.

The Plan was compiled by Charles A. Maguire and Associates of Boston, J. E. Greiner Company of Baltimore, and De Leuw, Cather & Company of Chicago.

The proposed complete system of expressways included the Southwest Expressway, beginning at the business district of Boston and running through Roxbury, Dorchester, and Hyde Park through Milton and Dedham, as well as the Belt Route, which was designed to serve as a bypass for traffic east to west and north to south. The paths of both these routes were mapped out through densely-populated areas inside and outside of Boston—and both projects were eventually halted and abandoned in the early 1970s.

The following maps, photographs, and reports document the history of these highways from proposal to abandonment—a decision that can be attributed to widespread public opposition, action, and grassroots organizing.

Beat the Belt

The proposed Inner Belt appears on this 1961 map in two dashed, green lines.

The Inner Belt was planned as an 8-lane expressway that, in tandem with the Central Artery, would form a ring road around the metropolitan area, cutting through Roxbury and Fenway, crossing the Charles River, and then running through Cambridgeport, Central Square, and Somerville.

As depicted on this 1959 map of the “golden semicircle,” it was designed to encircle the city, but in result, would completely destroy neighborhoods and uproot thousands. These densely-populated areas were described by planners as neighborhoods where real estate values were “low and…still declining,” and even suggested the “new service provided by the expressway” would “arrest the deterioration” and “aid in their rehabilitation.” In many cases, the neighborhoods identified as “declining” were racially and culturally diverse working-class communities that would bear the brunt of environmental and health concerns from highway pollution.

This geographic mismatch between one group of people’s needs and another group’s exposure is a key element of environmental injustice. Geographers use the term sacrifice zones to describe places that have been severely impaired by toxic landscapes.

As planned, the Inner Belt was projected to not only disrupt public transit and intensify noise pollution, but also displace over 13,000 people, local businesses, and fragment communities. With these concerns in mind, public opposition vocalized in the mid-1960s, with organized efforts in both Cambridge and Roxbury.

On February of 1966, a group of residents, led by Anstis Benfield, gathered in front of Cambridge City Hall to express their opposition. Adults and children, wrapped in winter layers, marched with signs that read Save Our Homes or Rights Not Roads and 5,000 People Are Worth More Than Two Miles Of Road. Before concluding, the group presented City Councilor Walter Sullivan with a signed petition calling the plan inhumane and demanding the highway be relocated to displace fewer families.

Later that year, demonstrators organized once again—this time at the inauguration ceremony of the new Massachusetts Institute of Technology president, Howard Johnson, where over 4,000 people (including presidents of 57 U.S. universities and colleges) were in attendance. Again, adults and children, labeled as picketers, marched with signs reading Beat The Belt and demanding support and action from MIT President Johnson.

Stop I-95

On the other side of the Charles River, residents in Roxbury mobilized efforts around not only the Inner Belt proposal, but also plans for the Southwest Expressway. The Expressway was designed as a twelve-lane extension of I-95 to relieve traffic congestion on Washington Street and Blue Hill Avenue, running through Milton, Hyde Park, Jamaica Plain, Roxbury, and the South End.

This 1964 map accompanied a report to determine the extent displacement if the Southwest Expressway were completed.

Starting in 1966, more than 500 homes and businesses between Forest Hills and the South End, including Jackson Square and Roxbury Crossing, were cleared for the Expressway; once again, the affected residents were generally from lower income, multiracial communities who were less likely to own cars, yet “it was their neighborhoods and communities that were…destroyed in an effort to make Boston more accessible to those living in the wealthier suburbs.” In the face of such destruction and displacement, opposition efforts were quick to mobilize.

In support of opposition, Boston Mayor Kevin White commissioned a BRA evaluation in 1968 to consider alternative transit design and land use.

Based in Roxbury, the Black United Front identified the expressway as a priority for action. In a statement of demands, the group wrote: “The Planned construction of the Inner Belt and Southwest Expressway are to be halted immediately and their continued planning and construction negotiated with the Black Community since both of these highways projects will radically affect the lives of the people in this community.”

In neighboring Jamaica Plain, a group of residents formed the JP Expressway Committee and collectively attended public hearings, wrote letters, and were responsible for the well known People Before Highways text that lined the parallel railroad embankment for over 20 years.

People Before Highways

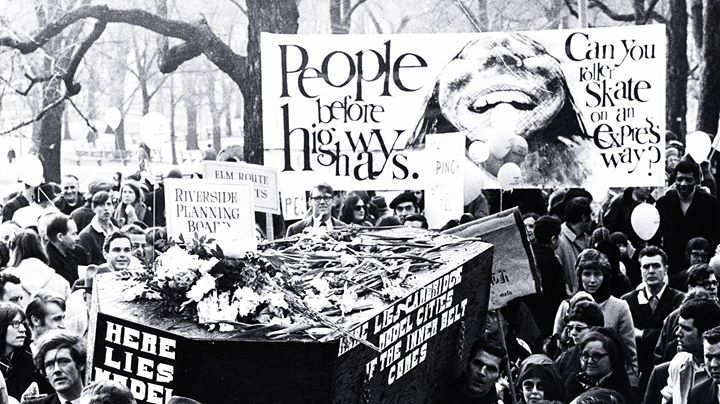

Efforts against the Inner Belt and Southwest Expressway started to blend toward the end of the 1960s, culminating in an organized People Before Highways Day at the State House on January 25, 1969. The rally attracted over 2,000 residents from across the metropolitan area, including the son of newly-inaugurated Governor Francis W. Sargent.

The January 25th protest brought together voices from various efforts.

Approximately one year later, opposition efforts proved successful and Governor Sargent (once commissioner of the Department of Public Works and in favor of the highway) announced a moratorium on new expressway construction to review alternative transit plans for the area. The restudy, known as the Boston Transportation Planning Review, was initiated in July of 1971 and by December of that year, had concluded that “plans developed in the 1940s and 1950s [were] inappropriate for the 1970s and 1980s.” And in a major win for anti-highway advocates, declared “the previously planned eight-lane facilities for the Southwest Expressway, 1-95 North, the Inner Belt, and Route 2 extension will no longer be considered,” as well as “all previous plans for the Inner Belt through Cambridge and Somerville.”

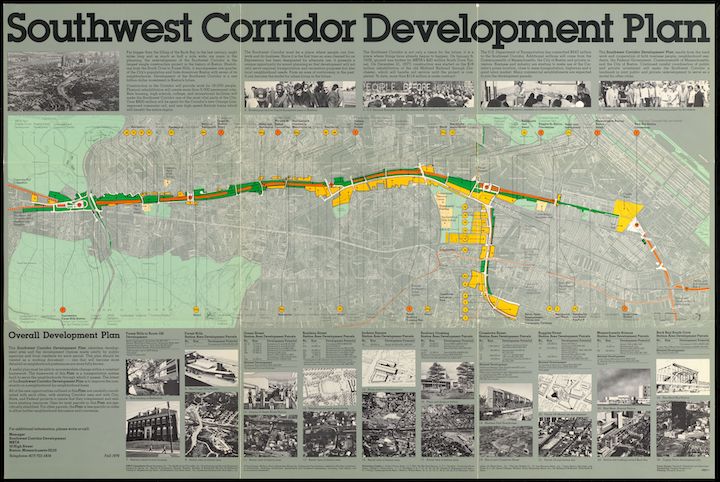

This Southwest Corridor Development Plan identifies development sites and choices made jointly by public agencies and local residents for each parcel.

In 1974, the funds originally reserved for the expressways were reallocated to support public transit projects, including:

- A Red Line extension from Harvard to Alewife, including a new station at Quincy Adams

- A new $743 million Orange Line and Amtrak-commuter rail extension, as well as 4.1-mile linear park, along the proposed route of the Southwest Expressway.

Today, the Southwest Corridor Park includes 11 playgrounds, 2 spray pools, 7 basketball courts, 2 street hockey rinks, 2 amphitheaters, 5 tennis courts, and 6 miles of trails for all to enjoy.

The anti-highway movement across the Boston metropolitan area included many efforts, actions, and stories that are not included in this article. We encourage you to continue your own research on the subject, using objects from our collections and the collections housed on Digital Commonwealth.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.