The five short essays featured in this digital publication were supported by the Leventhal Center’s Allmaps Research Fellowships. To learn more about how you can apply for an Allmaps Research Fellowship, reach out to LMEC’s Assistant Curator of Digital & Participatory Geography.

Introducing the essays

What do maps tell us about the changing city? How can you use digital tools to show how streets, neighborhoods and urban regions have changed? In the spring of 2024, students in my Brandeis University class called “Urban Worlds” were asked to explore this question using a combination of Sanborn fire insurance maps, Google Maps, and site visits within Waltham, MA. With the help of Ian Spangler, LMEC’s Assistant Curator of Digital & Participatory Geography, students learned how to georeference a Sanborn map using Allmaps. That allowed them to precisely place a segment of a historical map over a contemporary map to reveal how patterns in everyday life, land use, and geography have changed.

Read on to see examples of the wonderful ways students used Sanborn maps, digital tools, and careful in-person observation to document transformations in Waltham’s urban geography: department store closures that reflect shifting housing patterns, changes in the religious landscape that document immigration, and the industrial history of the Brandeis campus and its surrounding Waltham neighborhoods. As you read the student essays, you can explore this historical layering (or palimpsest) and visualize it by zooming in and out or adjusting the transparency of the maps.

- Dr. Jonathan Anjaria, Department of Anthropology, Brandeis University

From industry to education on South Street

By Lauren Farley

The city of Waltham has gone through many changes since its founding in 1884. In the mid to late 1800 and early to mid 1900s, Waltham was a booming industrial town, home to the Waltham Watch Factory and Roberts Paper Mill (for which the commuter rail station was partially named):

An account of the “Roberts” district and the Roberts Paper Mill, from MACRIS

Brandeis University’s founding in 1948 foreshadowed the kinds of changes that would take place within Waltham in the next 70 years—namely, changes in land use from industrial activity to educational facilities along its home of South Street.

Sanborn fire insurance maps are helpful for visualizing how these kinds of transformations have happened. For instance, the Sanborn map below illustrates the transition from an industrial-focused Waltham to a Waltham that was based more on the university student population. By georeferencing and examining the map in Allmaps, we can better understand how the Brandeis University campus changed between 1918, 1950, and today.

The Potter Press—the large pink building shown at the center of the map above—is a perfect example of this. Founded in 1912, the Potter Press was influential in the making of sales books with carbon paper, and attempting to shift away from that line of work led to a lawsuit in 1939 that eventually dissolved the press due to management disputes. The Potter Press building was constructed in 1921, on land bought from Roberts Paper Mill. Brandeis eventually acquired the building between 1966 and 1970, at which point they owned much of the land around the school. The map—as well as a visual inspection of the historical building versus the building today —suggest that Brandeis’ Epstein Building is the same physical structure of the Potter Press.

This single map sheet documents a changing landscape of ownership. Potter Press has become the Brandeis Epstein building, which includes housing facilities as well as the Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies department. Meanwhile, the Interlake Chemical Corporation was pasted over on the Sanborn map to become a “miscellaneous storage” building (today, the land is athletic fields). The surrounding infrastructure also speaks to Brandeis’ influence in Waltham, as nearby parking lots and multifamily homes cater to students, faculty/staff, and those commuting into Boston, rather than to workers in Waltham’s industrial facilities.

The changing face of downtown commerce in Waltham

By Eleanor Flynn

Today, Waltham’s Moody Street is renowned for its restaurants and food shops, but it may surprise you to learn that nearly 75 years ago, the area was known for something completely different: its department store. The georeferenced section of the Sanborn Fire Insurance Map below shows the Grover Cronin department store.

This was not a unique phenomenon to Waltham; department stores ruled the American downtown in the early to mid-twentieth century, providing one-stop luxury shopping experiences. However, Grover Cronin was the only department store on Moody Street that was not part of a national or regional chain, making it a local institution. Perhaps this is why it is the sole department store marked by name on the Sanborn map, despite being one of seven department stores located on this stretch of Moody Street in 1952.

Throughout the twentieth century, shifting cultural values and deliberate federal policies changed the face of commerce in Waltham, as seen in the pictures below. In the wake of postwar suburbanization, department stores’ profits faced increasing threats from suburban shopping centers.

The economic uncertainty of the 1970s redirected consumer priorities towards the convenience and low prices of shopping malls, making glamorous department stores like Grover Cronin relics of a bygone era. Additionally, the deregulation of the 1980s allowed for greater consolidation across the industry, essentially destroying the regional/local department store. These industry-wide shifts and policy changes took their toll on Moody Street; after celebrating its 100th anniversary in 1985, Grover Cronin closed its doors in 1989.

Cronin’s Landing Apartment Construction, ca. 1994 (from Digital Commonwealth

After Grover Cronin closed, commerce on Moody Street went through a transitional phase. The picture to the right, taken in the 1990s, shows the construction of Cronin’s Landing, a 281-unit apartment building that was built on the former Grover Cronin lot. This era in Moody Street’s history was challenging; in an interview with Wicked Local, Louise Butler of the Waltham Historical Society stated that “Once Cronin’s left, Moody Street had a ten-year period where it practically died and it took a ten-year period for the restaurants to bring it back.”

Moody Street has changed a lot since the 1950s. While the physical buildings have been preserved, as you can see in the chart below, what was once clothing, shoe, and department stores have become restaurants and food shops with cuisines from all over the world. The changes on Moody Street are a product of larger historical processes that transformed the structure and character of American cities, revealing just how much power urban policy has in shaping our past, present, and future.

Chart comparing Moody Street businesses in 1952 to 2024, with former department stores marked in *italics (compiled by Eleanor Flynn using a 1952 Waltham Directory)

| Moody Street # | 1952 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|

| 223 | *Grover Cronin Department Store | Cronin Landing Apartments |

| 240 | *Sears, Roebuck & Co Dept. Store | Gustazo Cuban Kitchen and Bar |

| 246 | Vacant | Kung Fu Tea |

| 254 | *J.C. Penney Dept. Store | Brewer’s Tap and Table |

| 265 | Liggett Drug Co | In a Pickle Restaurant |

| 270 | Harry’s Shoe Store | Raj Collections |

| 286 | Riseburg’s Clothing | Ponzu Izakaya Waltham |

| 289 | *Parke Snow Inc. Department Store | Paris Eye Care / Art Gallery |

| 299 | *F.W. Woolworth Co. | Family Dollar |

| 313 | Bell Hosiery Shop | Waltham Islamic Society |

| 315 | *Lincoln Stores Inc. Department Store | Waltham India Market |

| 326 | *Gilchrist Co. Dept. Stores | Global Thrift / Bistro 781 |

| 329 | Spencer Shoe Store | Bonchon Waltham (Asian fusion) |

| 331 | Allen Knitwear Store | Angel Tea (bubble tea) |

| 361 | Vanity Shop Women’s Clothes | Vinotta (Italian restaurant) |

| 365 | Edson Shoes | Gourmet Pottery |

| 367 | Waltham Camera Shop | Lizzy’s Homemade Ice Cream |

The ballad of Whitney Avenue

By Miles Goldstein

Tucked through an alleyway off of Waltham, Massachusetts’ commercial district, Moody Street, is the Whitney Avenue Municipal Parking Lot. In the 1950s, four or five homes and a modest plumbing business called Whitney Avenue home. Now, that’s all been torn down and paved over to become a parking lot and through street.

Whitney Avenue Municipal Lot, current day, versus a map of Whitney Ave. via Atlascope

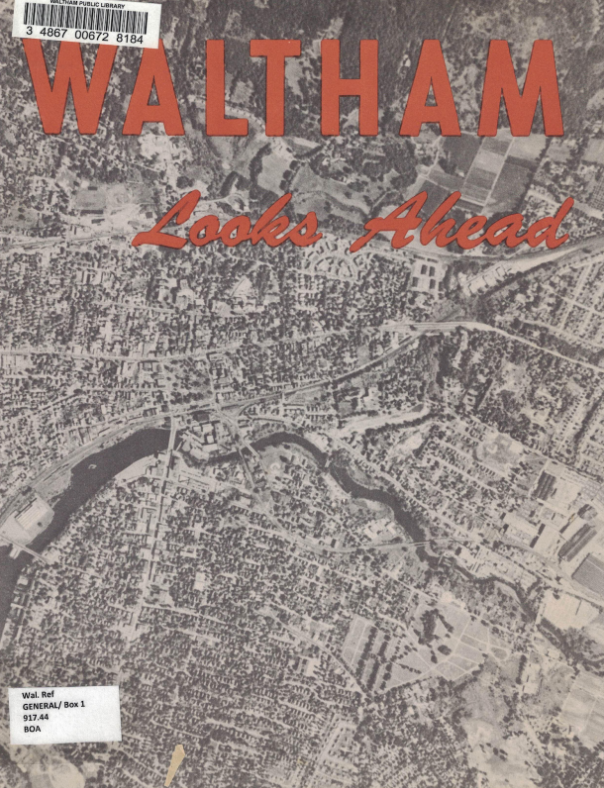

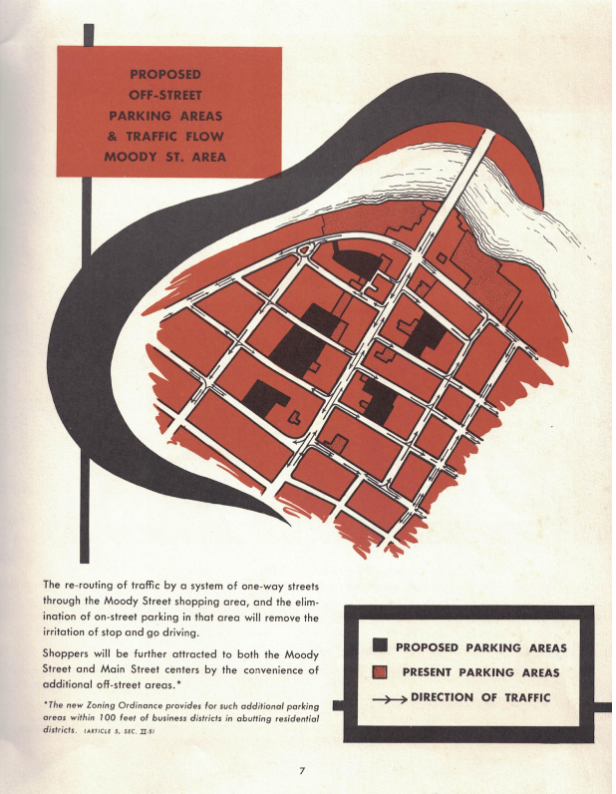

While displacing people from their homes in order to build a parking lot a generation later may feel ethically dubious, it happens all the time. To answer the question of how and why, we can return to “urban renewal,” a series of efforts in the mid-twentieth century to modernize American cities and eliminate so-called blight. In 1955, as part of their urban renewal program, Waltham introduced a master plan to eliminate “blight” and modernize the city. The city’s communication campaign, “Waltham Looks Ahead,” shared a new vision for Waltham’s commercial district that included stores for travelers far and wide with “convenient off-street parking” in lots built on residential land, like on Whitney Avenue. But when the priority for the land became attracting people from outside the city and maximizing profits, the needs of the people on the land—like those living in Whitney Avenue—fell by the wayside.

Just a year before Waltham published its master plan, the Supreme Court ruled in Berman v. Parker that cities and states could seize land they deemed blighted via eminent domain, so long as it served the “public good.” They placed the power to determine public good in the hands of cities and states, provided they could furnish a development plan, like Waltham’s 1955 master plan. Empowered by Berman v. Parker, the city could seize and demolish private property for the public good—which, in this case, it had interpreted as building parking lots around Moody Street.

Section of Waltham Master Plan describing eminent domain use in the Whitney Avenue area (from Waltham Public Library)

Traffic and congestion remain a problem along Moody Street to this day, and street parking is still common—but on some nights in the summer, the city of Waltham closes off the streets to cars and invites pedestrians to eat, play, and socialize freely. During these events, Moody Street comes alive with sounds, smells, and people, enjoying what is usually the congested heart of Waltham’s commercial district. The life and vibrancy of a city that embraces pedestrians carries with it a certain indescribable magic. Perhaps, then, looking at maps with a critical eye can teach us to safeguard what we have against calls that it must be renewed.

A lost commuter rail

By Max Woolf

Greater Boston’s Commuter Rail is a staple of the MBTA’s transportation infrastructure. It is the nation’s 5th largest commuter rail system, moving 19 million riders yearly. However, today’s system is not at its maximum capacity. The network has expanded and contracted since its inception in the 1970s, leaving ghost lines.

One of these lines, the Central Massachusetts Railroad (CMR), can be discovered by looking at Sanborn maps. Insurance companies created Sanborn maps to assess fire risk during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but their meticulous detail now helps us look into the past and see what has changed. This Sanborn map from 1930, georeferenced using Allmaps, shows an old CMR station overlaid onto a modern-day map of the suburb of Waltham. Notice the Waltham Highlands Station in the center; you can also see the old railroad track which once served a whole portion of the state but is no longer there.

The Railroad’s creation was triggered by frustration from suburbanites who lacked transportation to the city. Initially, the line went as far as western Massachusetts, but inadequate use caused it to serve just four towns west of Waltham.

Eventually, the shrinking service was incorporated into the MBTA’s Commuter Rail in 1959. Over the next decade, the line continued to be plagued by low ridership problems. The rising use of cars, and more importantly, car-based infrastructure, were a significant reason why ridership remained low. As new highways were being built, fewer and fewer people were choosing to use mass transit.

Waltham Highlands Station today (photo by Max Woolf)

By 1970, the line was set to close. One last push by suburban residents clinging on to hope that it could be salvaged managed to delay the closure. However, on November 2, 1971, the CMR sent its last commuter train and closed for good. Fifty years later, the remnants of the line remain. The once bustling Waltham Highlands station is now an insurance agency, and the railroad is now a bike path.

This commuter rail line’s failure is indicative of America’s shift to car-centric transport. Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century, substantial federal highway stimulus packages paved the way for infrastructure like the Mass Pike, which diverted much of the western suburban traffic away from rail. Today, residents of Waltham Highlands must use a car to travel directly into Boston because they are served by only one bus stop that drops them at Waltham Commons. In recent years, public transit investment has become a more salient issue and some advocates have pushed for the expansion of commuter rail. If the past is any indication, large-scale civic engagement like the kind that led to the creation and delayed closure of the CMR will be necessary to move any plans forward.

Immigration and landscape on Moody Street

By Anthony Ruiz

Aguas, no te caigas—a line that confirmed one was in Waltham, Massachusetts. Throughout the city, subtle details demonstrate how immigrant populations are reflected in the landscape and language, such as the use of Guatemalan slang like aguas, which means “be careful.”

Beth Eden Baptist Church in Waltham (photo by Anthony Ruiz)

In the 1800s, Irish immigrants were among the earliest groups to arrive in Waltham, followed later on by Italians and other Europeans. Within a predominantly Catholic northeastern United States, these immigrants brought Protestantism to Waltham.

As the georeferenced map below highlights, the lasting impact of immigration patterns on the infrastructure and organization of the city are still visible in the Moody Street landscape. The Beth Eden Baptist Church, for example, was first built in 1891 and still stands tall on Maple Street in Waltham’s South Side.

Immanuel United Baptist Church bulletin board (photo by Anthony Ruiz)

More recently, Waltham has experienced an uptick of Guatemalan and Ugandan immigration, the city’s two highest immigrant populations. These immigration patterns are visible in Waltham’s religious institutions, such as the Immanuel United Methodist Church on Moody Street, which offers services in both Luganda and Spanish.

Considering that Beth Eden and Immanuel United have both existed for over a century—and have served to accommodate changing city demographics over the years—their presence attests to the continuities of the Protestant influence in Waltham. We can also see the influence of Guatemalan immigrants in other parts of the built environment, such as how parking signage around the city accentuates Spanish language translation relative to English. Today, a stroll through Waltham bears out Jane Jacobs’ notion that cities should be busy and full of life.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.

*)](/images/blog/walthamEssays/flynn_moodycrescent1950.jpg)

)](/images/blog/walthamEssays/woolfImage01.png)