As part of his first week of work, we spoke with Ian Spangler, the new Assistant Curator of Digital & Participatory Geography at the Leventhal Map & Education Center. Ian holds an MA in Geography from the University of Kentucky, and is currently completing his dissertation on the politics of digital real estate information.

In his role as Assistant Curator of Digital & Participatory Geography, Ian will be continuing to strengthen and develop our work in the geospatial humanities. That will involve everything from projects in our digitized historic collections all the way through experiments with modern mapping and critical spatial analysis.

Ian has been learning his way through the Bending Lines gallery in his first week on the job.

Garrett Dash Nelson: Ian, we’re so excited to have you on board here at the Leventhal Map & Education Center. Tell us a little bit about your background—what led up to your new role with us?

Ian Spangler: It’s wonderful to finally be here! As an undergraduate at the University of Mary Washington, I double majored in Geography and English. People would say, “Geography and English? That’s a strange combination!” —but it really wasn’t.

I think the combination of those two fields of study fits with the work at the Map Center quite well, since I see the LMEC as a kind of spatial storytelling institution. My coursework in literature and creative writing nurtured my interests in narrative, while the geography curriculum grounded the stories I wanted to tell in empirical context. That combination of narrative and description forms a distinct kind of geographic thinking that I find important for making sense of the world today, and it’s definitely a kind of thinking that the LMEC cultivates with the programming, tools, and scholarship that are offered here

Anyway, I’ve always been fascinated by the power of narrative to shape space, and vice versa. In 2014, under the guidance of some really wonderful people at UMW, I got involved in a research project that examined representations of slavery at US plantation museums. This was a pretty formative experience for me, and in many ways it set the stage for the kinds of things I’d be interested in many years later: namely, how racialized landscapes in the US are produced, remembered, and sometimes forgotten.

In 2016, I entered the graduate program at the University of Kentucky, where I became more interested in digital technologies and urban housing, and that’s more where my research sits nowadays. The GIS skills that I had picked up in college proved quite useful for investigating topics like short-term rental listings in New Orleans, where I conducted research on the uneven impacts of Airbnb listings. Even though my research isn’t focused on New Orleans anymore, I’m still really fond of the city.

A 1986 topographic-bathymetric map of New Orleans, created with Landsat-5 MSS imagery by the USGS

While I do consider myself a geographer, I still maintain an active commitment to creative writing. I tend to write memoir-type, creative nonfiction stuff that engages with the complicated attachments that people develop to the places they inhabit—which is still, of course, a very geographic process!

GN: You mentioned “geographic thinking”—could you say a little more about what you mean by that?

IS: By “geographic thinking,” I just mean a particular approach toward puzzling out why things happen the way they do. In my view, “thinking geographically” means thinking from and with the concept of space, which is to say, thinking with an eye towards difference. That’s one of the most foundational concepts in geography—I mean, the “first law” of geography is that everything is related to everything, but near things are more related than distant things. This statement turns out to be more a provocation than a hard-and-fast rule, but it gets us going.

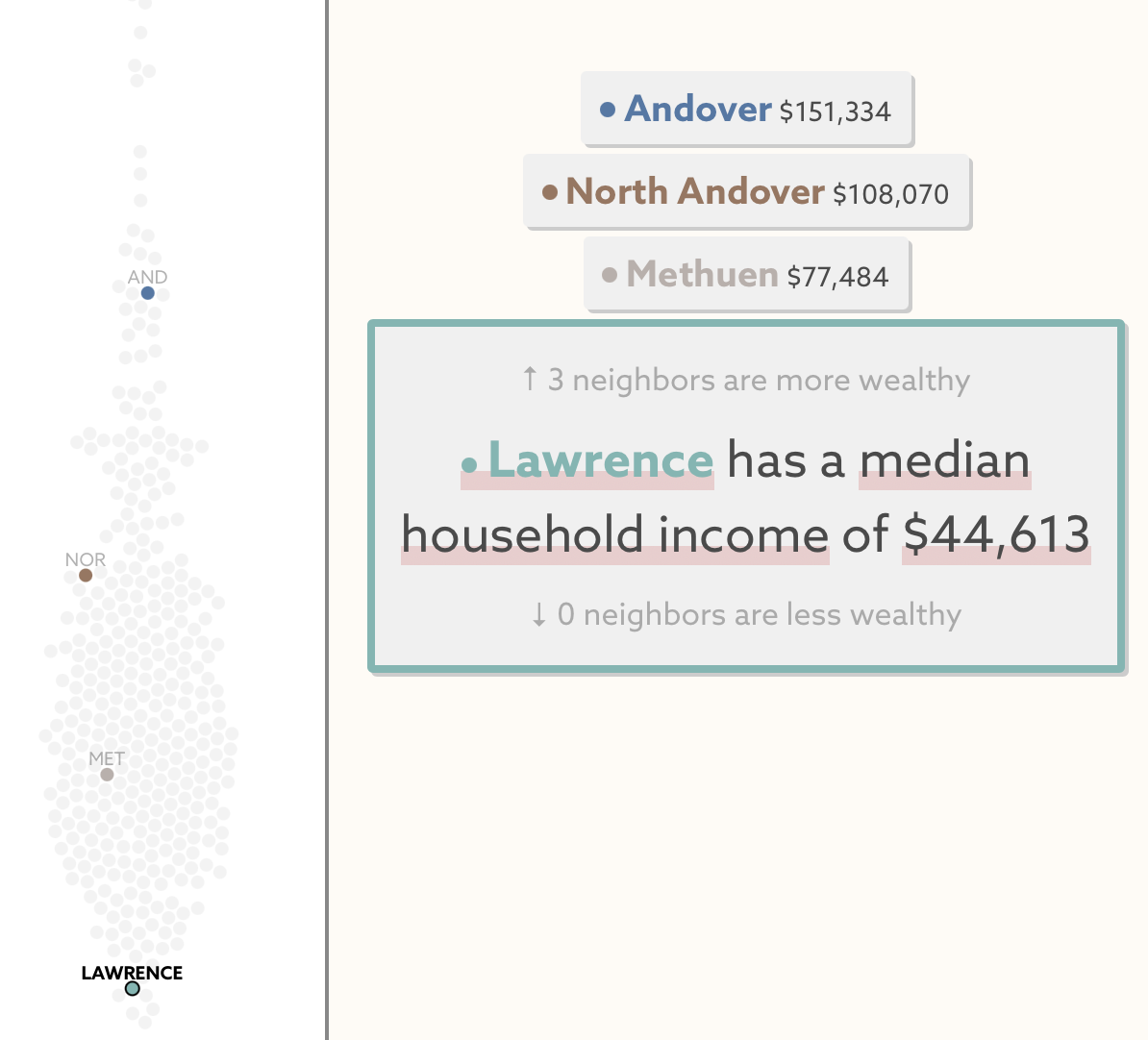

Extreme spatial disparities characterize many neighboring towns in Massachusetts, seen here in our visualization of municipal inequality

Why is this different from that? How did those differences come to be? How do those differences get maintained across space and time? Those sorts of questions guide lots of geographic thinking, and they can be applied in so many contexts: Why is this type of vegetation found here, but not there? Why does this neighborhood have so much green space, but not that one?

Then you start to ask, well, wait a minute: things A and B distant are much more alike than things X and Y near. What’s up with that? It puts the “first law” into question, and now you’re down a rabbit hole. That’s a kind of basic way of getting at this mode of reasoning, of geographic thinking. We all inhabit and share many spaces at once. Those spaces are fundamentally differentiated, and they’re experienced differently by different people, at different scales. From there we can really start to make sense of bigger picture historic, political, and economic processes that impact our everyday lives.

GN: How do you see yourself taking this concept, one of the fundamental insights of human geography, and applying it to your work here at the Leventhal Center?

IS: All of that was a somewhat long-winded way of describing why the LMEC is such an exciting organization to me. Like I said before, I see the LMEC as an institution that’s committed to spatial storytelling. We only need to look as far as Bending Lines for a primer on the power, and limits, of maps as a form of geographic thought. It’s exactly that tension between power and limits that has always made maps so interesting to me.

More specifically, I admire the initiative that the LMEC has taken to expand into digital services. In addition to having an extensive physical collection, we also host a wide range of digital tools and modules for map education. I think that distinguishes the LMEC, and creates lots of exciting possibilities for telling new stories.

GN: We’re thrilled to be working with you on all of these topics. What are you most excited about getting started on first?

IS: Perhaps predictably, one of the things I’m most excited about is diving into the amazing digital mapping tools that are on offer here at the LMEC. Atlascope, our tool for examining and comparing historical atlases in Boston, was one of the first things that really stuck out to me about the LMEC. I can’t wait to get more involved with Atlascope’s development, not to mention the other exciting georeferencing projects that we have on the docket.

GN: Do you have any memories of maps that inspired you, or really spoke to you?

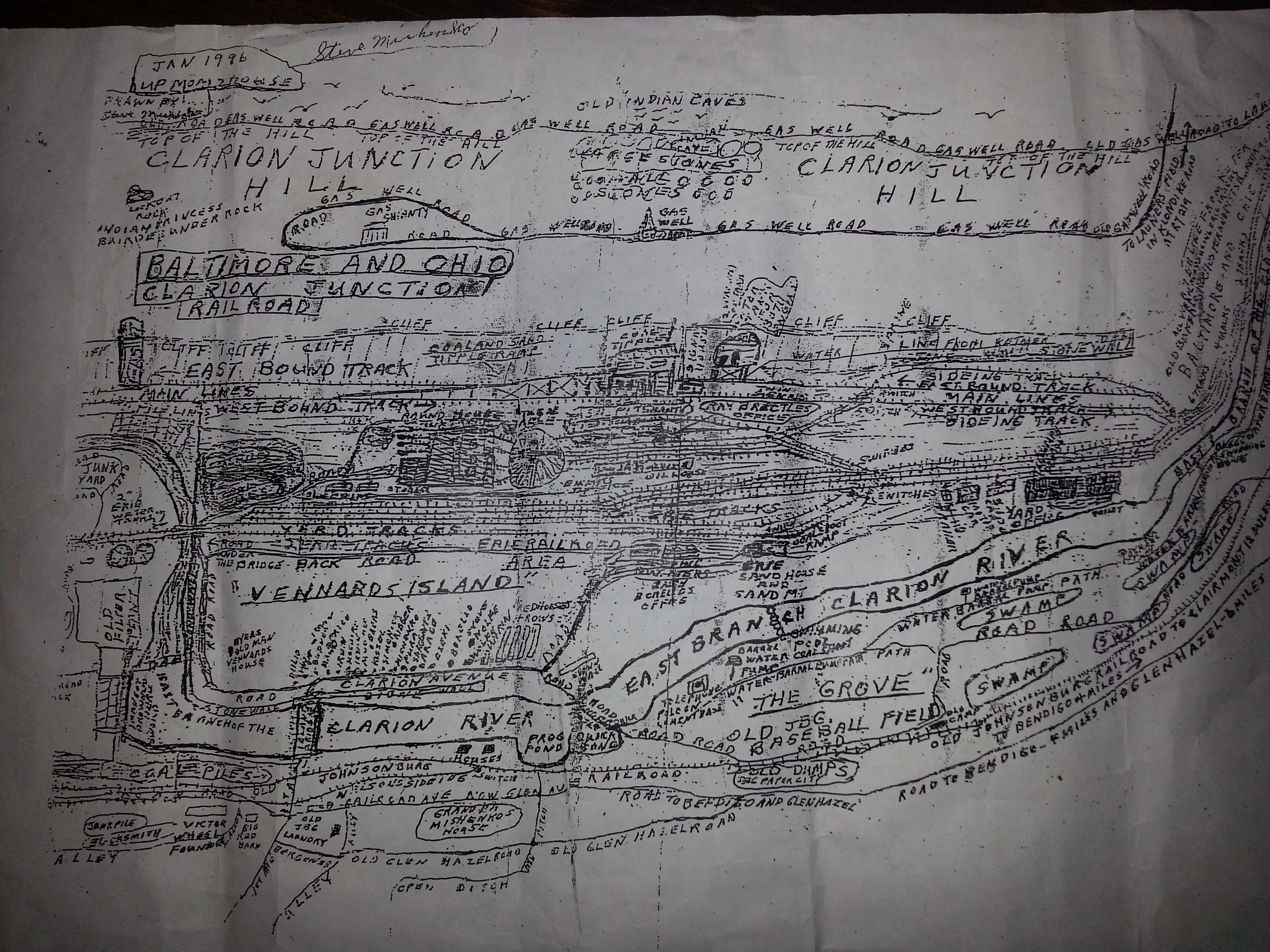

IS: When I was 18 or 19, we were packing up all the things in my grandma’s Johnsonburg, Pennsylvania home, when we came across a couple of maps hand-drawn by an old neighbor, Steve Mishenko. The story went that Steve never owned a car, and he walked most places he had to go. It followed that his mental map of the area was quite sharp, and lucky for us, he put that mental map down on paper.

Steve Mishenko’s map of Johnsonburg, PA, January 1996.

Steve’s maps were imperfect, with railroad lines that recklessly criss-cross and features that are difficult to parse. Still, for all the weird contradictions, I love those maps. They remind me of home, in a nostalgic way, which serves as a reminder that maps serve more purposes than wayfinding or navigation.

Looking at his maps, I’m always struck by how they seem to represent multiple dimensions at once. They remind me of bird’s eye view maps, which were a popular kind of pictorial map that highlighted major landscape features instead of accurately capturing scale.

An 1895 bird’s eye view of Johnsonburg (Library of Congress)

GN: Alright, last question: having just moved from Kentucky to Boston, what are you most excited about as you get to know the city?

IS: I loved my time in Lexington, but it’s a landlocked state, and I did miss the water. I’m really looking forward to spending time along the coast, both in Boston and throughout New England more broadly. Maybe I’ll even try learning how to sail!

As I settle in, I’d love for anyone to reach out to me. Feel free to drop a line with suggestions on what to explore in Boston, questions about the Map Center, or anything else! —Ian

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.