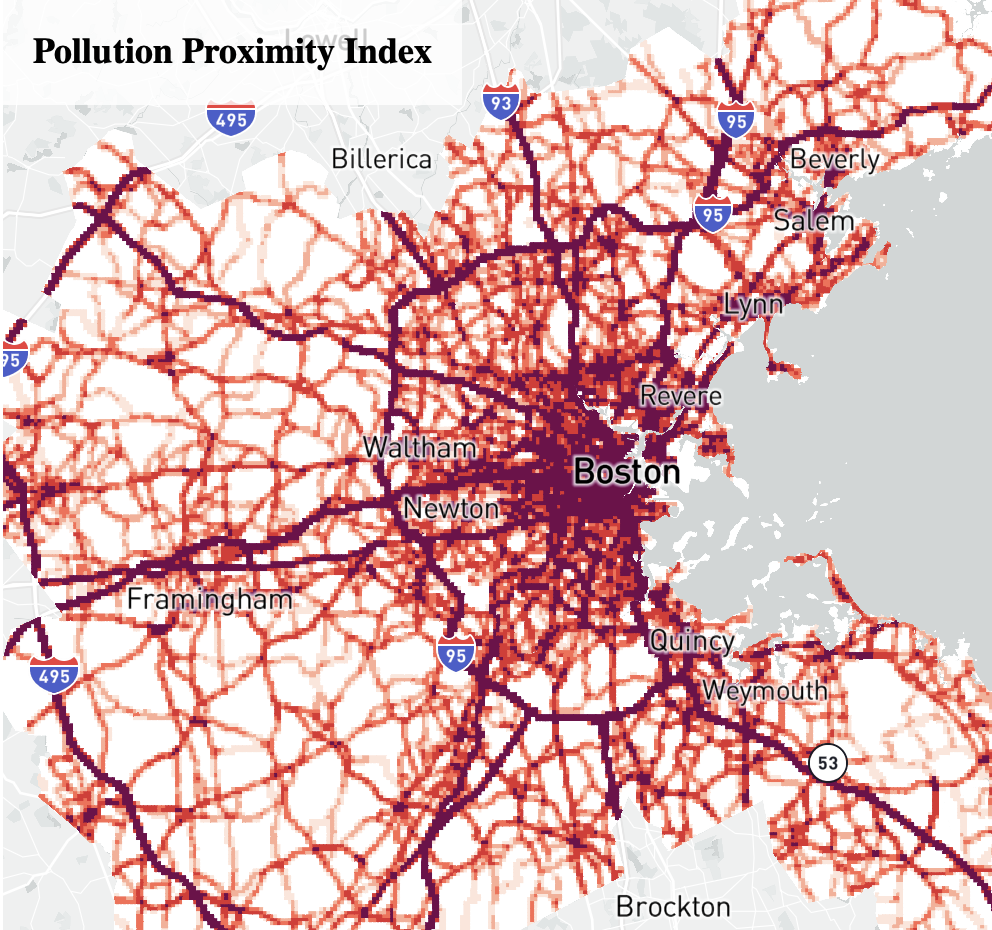

In May of last year, as the COVID-19 pandemic was raging across the country, researchers at the Metropolitan Area Planning Council looked at what parts of Boston were experiencing the most severe comorbidities due to unhealthy levels of air pollution. What they found was a pattern of environmental racism: “we observe that residents of color are disproportionately living nearer to the higher levels of pollution,” the report’s authors concluded.

Vehicle pollution data from the MAPC study of racial disparities in hazardous air quality

For those who have come to think of environmental concerns like pollution control and social issues like racism as distinct and disconnected challenges, the term “environmental racism” might seem at first like an unfamiliar conjunction. Even before the origins of the modern environmentalist movement in the 1960s, efforts to protect and improve the human landscape have often been cast in terms of universal benefit. A well-kept public park, a river free of toxic chemicals, or a stable global climate all seem like amenities that can be shared by all, free of discrimination by race, class, ethnicity, nationality, or gender.

In reality, however, the advantages of a well-protected environment—and conversely, the hazards of a damaged one—have rarely been evenly spread. Instead, both historically and in the present day, access to a safe, healthy, and pleasant environment has been controlled not only by where you are, but also who you are. Public and private designs for green spaces, pollution controls, and remediation projects have been lavished on communities already at the center of power. Meanwhile, the places where the environment has been turned into a sacrifice zone are most likely to be the same places where poor families, immigrants, and people of color find themselves living and working. Even in vast crises like the climate emergency, which seem to have thrown all of humanity together in the same common fate, these inequalities persist. “We may all be in the Anthropocene,” writes Rob Nixon of the world-historical era in which humans have become an environmental force on a global scale, “but we’re not all in it in the same way.”

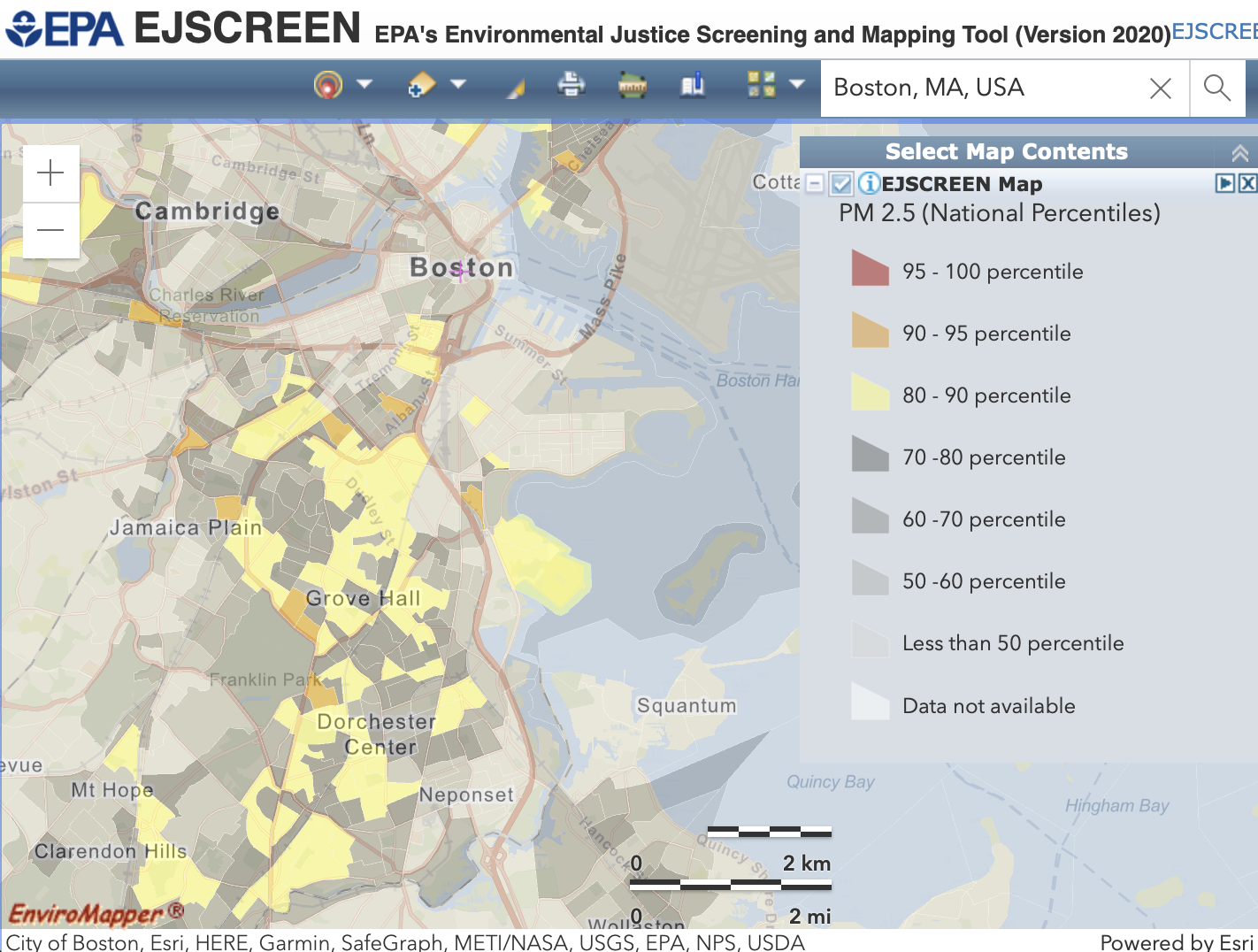

A screenshot from the EPA’s EJSCREEN environmental justice mapping platform

What links these uneven environmental and social patterns together is geography. Sometimes they quite literally map onto one another. For this reason, maps can provide powerful tools for understanding—and challenging—these injustices. For instance, one of the most important resources for the Environmental Protection Agency’s environmental justice division is a mapping interface known as EJSCREEN. Just a few weeks ago, Massachusetts Senator Ed Markey introduced a bill “to establish the Environmental Justice Mapping Committee.” Different forms of geographic investigations, from complex spatial analysis tools to participatory community maps, can be used both as documentary evidence and tools of resistance.

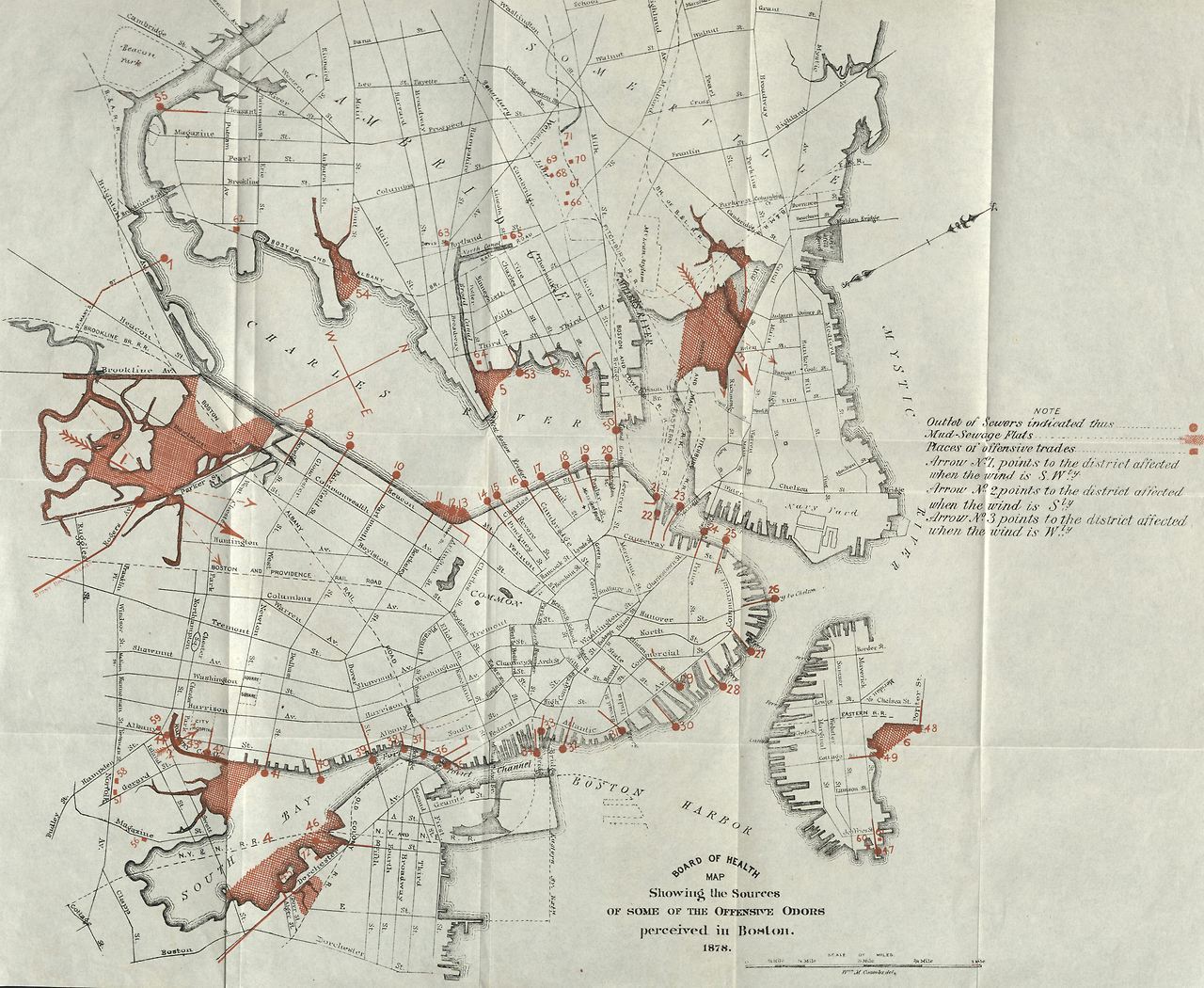

An 1878 map of “offensive odors” (from the City of Boston Archives)

In March 2022, we’ll be opening a major new exhibition at the Leventhal Map & Education Center called More or Less in Common: Environment and Justice in the Human Landscape. In this exhibition, we’ll be exploring how maps and geography provide a way of understanding how the control of nature has intertwined with struggles for justice. Some of these stories date from a period far earlier than modern environmentalism, like the 1684 deed in which white settlers officialized their taking of what is now East Boston as private property, or the 1878 map of “offensive odors” which shows how Boston began filling in estuaries in order to please the senses of elite neighborhoods like the Back Bay.

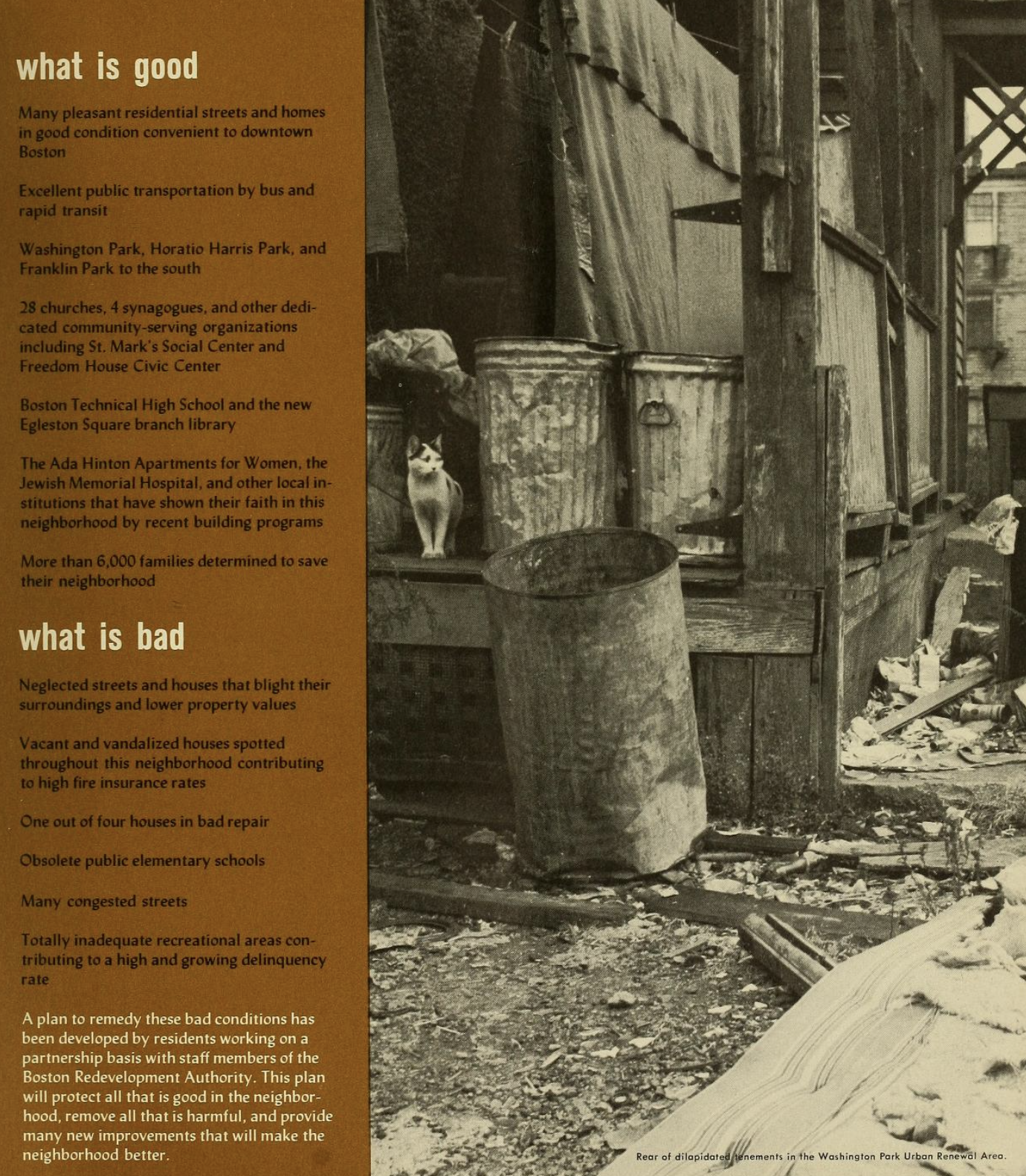

A page from the BRA’s proposal for redevelopment in Washington Park shows how environmental degradation was used as a justification for clearance and rebuilding

Other historic collections examine how the politics of environmentalism emerged. An 1852 map of Concord invites us to think about the enduring legacy of Henry David Thoreau’s “life in the woods,” while an 1886 plan for Beacon Street in Brookline documents the historic connection between environmentalism and racially-restricted suburbanization. Still others draw our attention to the often-forgotten role of the environment in the civil rights struggles of more recent years: a 1963 plan for Washington Park shows how urban renewal was pitched as a way to correct disinvestment in Black neighborhoods, while records of a 1970s preservation effort in Concord show how environmental concerns were sometimes used as a pretext for propping up exclusionary residential geographies.

And, given our commitment to not only preserving historic maps but also advancing their future, we’ll be creating new maps that seek to visualize the stakes of environmental justice struggles of today and tomorrow. Maps help us plan for the future as well as document the past, and thus the choices about whose visions get to be represented on such documents is shaped by other forms of inclusion and exclusion. We’ll look at maps that imagine proposals and solutions for issues from climate change to decaying infrastructure that emphasize remediating social and environmental ills as part of the same challenge.

An excerpt from the 2100 Project atlas shows natural disasters that have been made worse by climate change, exacerbating the injustices already borne by people in poverty and communities of color

While we’ll be including many examples from Boston and New England, More or Less in Common will also look at how maps can manifest the global realities of today’s environmental challenges, from oil spills in the Niger Delta, where rampant extraction feeds the gas pumps of Massachusetts, to the likelihood of mass displacement that will be a consequence of unequal exposure to the risks of climate change.

More or Less in Common is timed to coincide with the bicentennial anniversary of one of Boston’s most influential environmental planners, the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., who was born in 1822. Olmsted’s own career offers one way of considering the complicated spatial politics of environmental management. On the one hand, Olmsted was a deep believer in the public role of park design, and he almost singlehandedly created the political justification for bringing open space under the ownership and management of the government. His parks advocacy therefore represented one of the major steps forward for the early welfare state, and established principles about the common good that survive in today’s environmental campaigns. On the other hand, however much Olmsted genuinely believed in the egalitarian goals of his projects, in reality they sometimes became mechanisms for maintaining systematized inequality. In Boston, Olmsted’s famous Emerald Necklace forms in some places the dividing line between communities that are amongst the richest in the country and others that are languishing in poverty. The final link in the Emerald Necklace, the “Dorchesterway” along Columbia Road, was never completed; today, some blocks along Columbia Road have median household incomes that are less than a tenth of the incomes of similar blocks in Brookline.

The Olmsted firm’s 1897 plan for Columbia Road was never realized

Consequently, issues of spatial and environmental justice are keywords for the group organizing Greater Boston’s Olmsted Bicentennial (the group’s placeholder website will soon be updated with program offerings). For us at the Leventhal Map & Education Center, while we’ve hosted several different previous exhibitions on public spaces and the environment, this will be our first exhibition that makes environmental justice its organizing theme. We’re already deep into planning our exhibition together with related programs for the public, students, and educators, and we hope our work will be part of a broader conversation seeking to show that environmentalism must directly confront pernicious, deeply ingrained social inequalities—and reckon with the fact that such themes have been left out of environmental politics too often.

Want to keep in touch with what we’re planning for More or Less in Common? Consider following us on social media or joining our mailing list. And if you’re working on a project which involves mapping environmental justice, either in Boston or beyond, please let me know—we’ll be looking for examples and partners of all different backgrounds to help tell this important story.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.