This digital publication was supported by the Leventhal Map & Education Center’s Small Grants for Early Career Digital Publications program and the Harvard Map Collection.

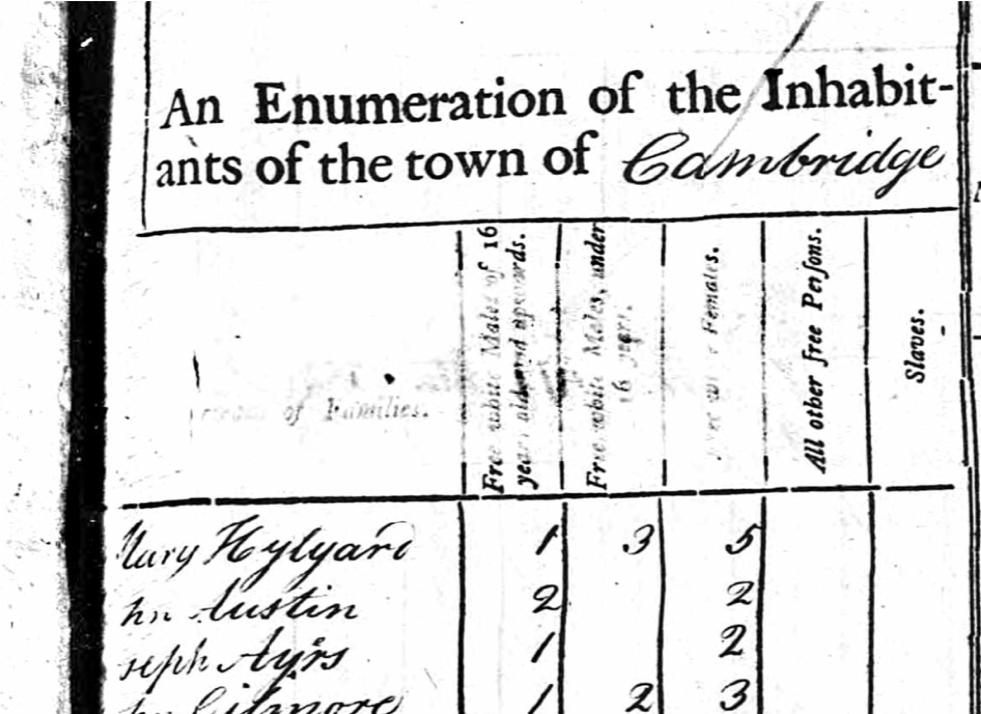

In August 1790, the United States of America conducted its first federal census. The data collected was minimal; census takers recorded no addresses, no professions, and no names except for head of household. Household members were tallied in demographic categories: race, and—for white people only—gender and age. Even as the demographic categorization of white people grew more specific in the following censuses, it wasn’t until 1820 that census takers did anything more than tally people of color in a single column titled “All other free Persons.”

Though this data is thin and provides only a very rough glimpse into the geography of Black urban life in the early decades of the country, it does give us a starting point from which to explore where—and how—Black people made their homes. This trace of data is where our research into Black Cantabrigians1 began.

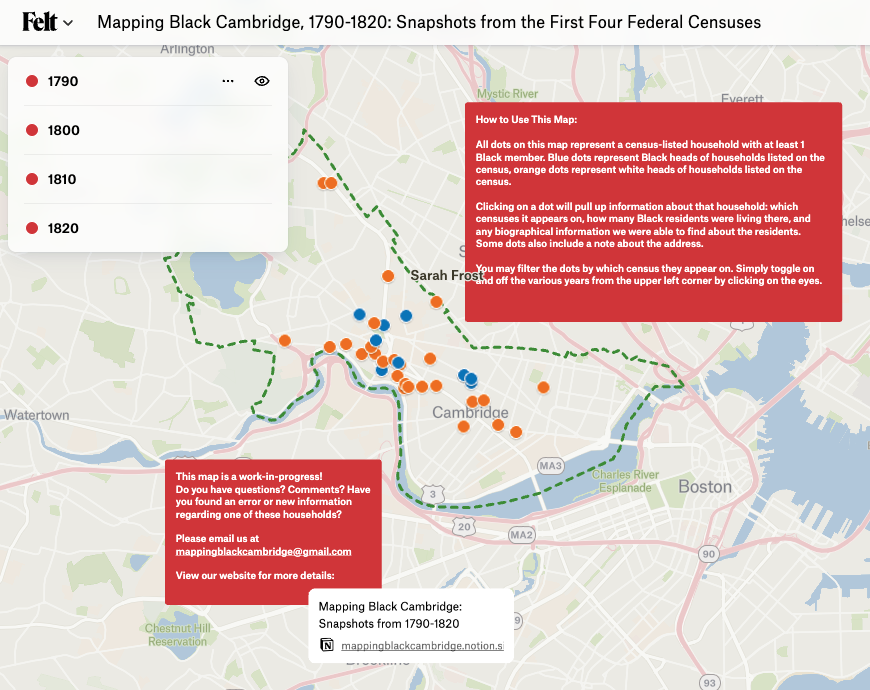

The aim of our research has been to document Black Cantabrigians in the years 1790–1820 and uncover the identities and stories behind the numbers in that “all other free persons” column on the first four national censuses. Across the four census years, we found 66 unique Cambridge households with at least one Black resident. Of those households, we were able to identify an address—and thus place a dot on the map—for 35. Our interactive map displays these findings:

While the map is not a complete record of Black Cantabrigians in this period, it provides four partial snapshots of the years the census was taken (1790, 1800, 1810, and 1820). This means that anyone who moved in and out of Cambridge between these years or was not at home on census day is not accounted. But these four snapshots do offer a suggestive starting point for historical research into the residential patterns of Black life at that time.

To fill in details that the censuses lacked, we turned to other sources of demographic information, including vital records, newspaper archives, historic accounts of Cambridge, and modern scholarship. These sources also left much to be desired, and we had to work carefully across them to piece together snippets of information to construct biographies. To illustrate this process, here is the chronicle of our search for Violet Cassimere, as it offers a good example of some of the puzzles this research presented. You can see Cassimere on the map at 348-350 Broadway, but to place here there, we needed to go on a historical detective mission.

Finding Violet

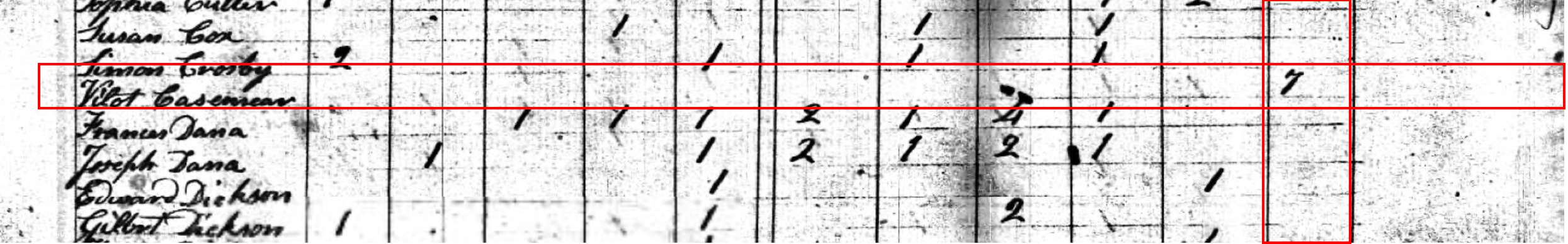

In 1810, “Vilot Casemear” appears in the Cambridge census for the first time:

A screenshot of “Vilot” in the 1810 Census.

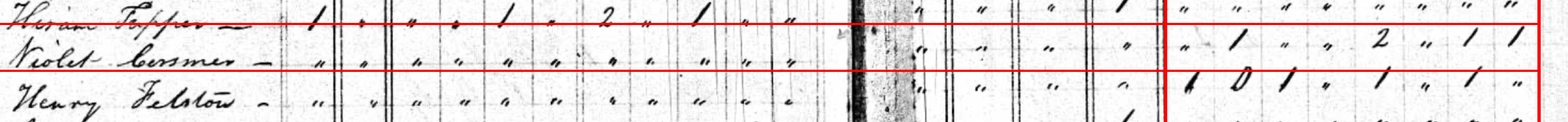

She is the head of a household of seven people, all of whom are tallied in the “All other free Persons” column. In 1820, a “Violet Cersmer” is in the census, likely the same person as “Vilot Casemear.” This time, she is the head of a Black household of five: two girls, two adult women, and a young man:

Violet appears in the 1820 census, along with other members of the household.

Our first task was to try to find an address for Violet. To do this, we used Christopher Hail’s Cambridge Buildings and Architects, an index of house tax documents and property deeds in Cambridge. In Violet’s case, her address was relatively easy to find—Hail found her paying house tax on a 1½ story house at what is now 348-350 Broadway in 1810. In 1813, she purchased this property.

This house no longer exists—it was razed in 1918—but the lot is at the present-day corner of Broadway and West Place, near the Cambridge City Hall Annex. We placed Violet at this address both in 1810 (the year she started paying house tax) and in 1820 (we found no record of her linked to another property after purchasing this one in 1813). Now we knew where she may have lived, but who was she? And who was living with her?

From Cassimere to Zophrion

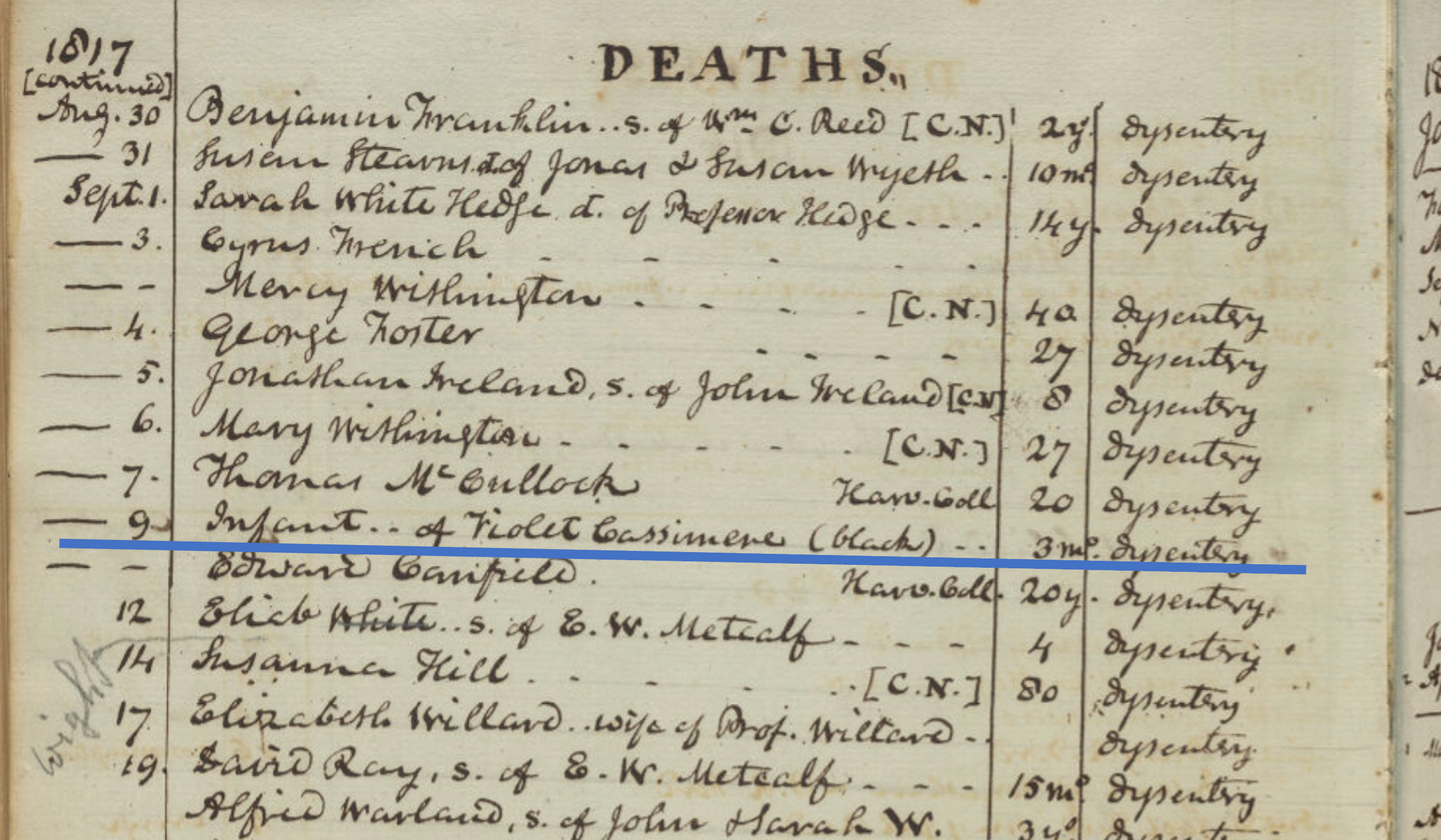

Because we had noticed a wide variety in the spelling of her last name—there were four variations just between the censuses and Hail’s index!—we searched the vital records for any approximation of the name “Casemear.” Our first breakthrough came from a death record at First Parish: an “infant…of Violet Cassimere (black)” who died aged three months in 1817.

The death record for Violet’s baby.

It appears her baby died in a major dysentery outbreak, as all of the deaths recorded at First Parish that month were due to dysentery. This revealed that Violet had had at least one child, although this child was not alive in 1810 or 1820 and therefore would not have been counted on the census. We then widened our search to just “Violet” and came across a birth entry from 1806: Christina Zophrion, born to Casimir and Violet. This seemed like too great a coincidence that there was a Violet Cassimere living in Cambridge at the same time as a couple named Violet and Casimir.

Was Violet Cassimere in fact Violet Zophrion, but using her husband’s first name as her surname?

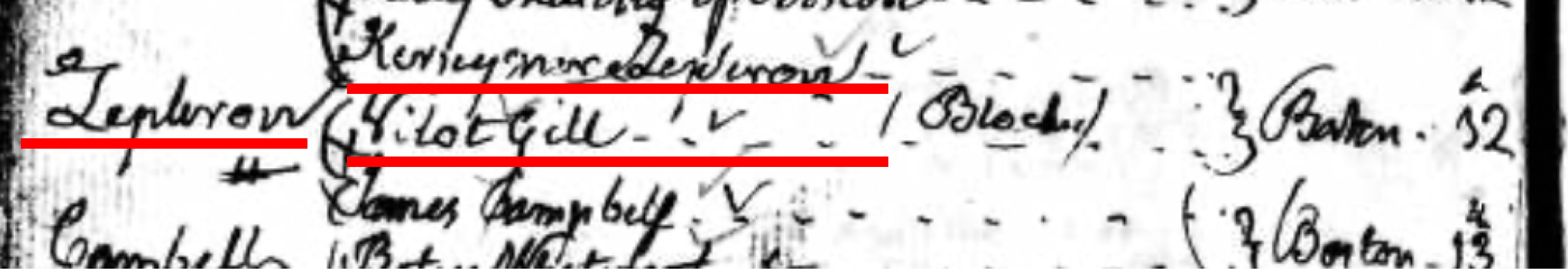

We proceeded to look for variations on Zophrion in the vital records. We found an 1801 Boston marriage certificate for Vilot Gill and Kerseymer Zephron, confirming that this couple was married in the area:

The death record for Violet’s baby.

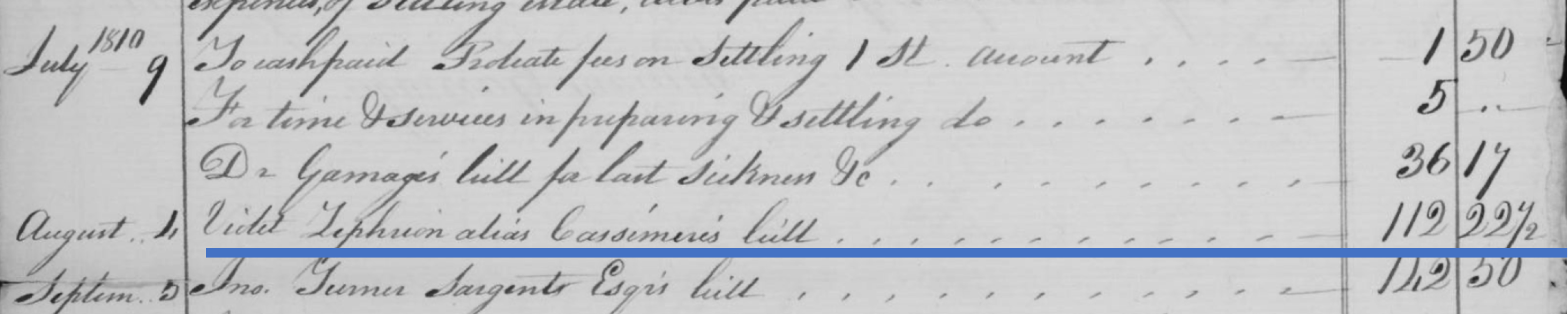

We then found an advertisement in the newspaper from “Violet Zyphron,” offering her services as a laundress in 1807, the year after Christina Zophrion was born. All of this told us that Violet Zophrion had married, had a daughter, and worked as a laundress in Cambridge. Meanwhile, we also knew where Violet Cassimere lived in the city and how many people were living with her in 1810 and 1820. But were Violet Zophrion and Violet Cassimere the same person? An 1809 probate record of a Black man named Fife Downs confirmed this theory: a bill of over $100 was paid to a “Violet Zephron alias Cassimere.”

The death record for Violet’s baby.

Mysteries remain about Violet and her family, such as what might have happened to her husband, Casimir. It seems unlikely that he was regularly living with Violet by 1810 because he was not named as the head of household, and Violet paid house tax and purchased land under her own name.

Interestingly, Violet received the money from Fife Downs’ estate the year before she began paying house tax. Perhaps this money allowed her to establish her own household. Violet had a baby in 1817, but in 1820 there was not a man old enough to be Casimir recorded in Violet’s household. Aside from Violet and Christina, we were unable to uncover the identity of the others in Violet’s household (five others in 1810 and three others in 1820), although we did find a few possibilities (you can click on Violet Cassimere’s dot in the map to learn more). Finally, we found no trace of Violet after 1820, leaving us to wonder what the rest of her life looked like. Nevertheless, these snapshots of Violet’s life alongside those of other Black Cantabrigians give insight into a growing community in Cambridge in these years.

Furthering research into Black Cambridge

We are hoping that this map opens up new avenues of research for Black history in Cambridge. If you have any questions or knowledge that you would like to share, please contact us at mappingblackcambridge@gmail.com

Joan Brunetta and Eve Loftus both grew up in Cambridge and went on to study History at Smith College. Eve has recently finished an M.Phil. in Public History and Cultural Heritage from Trinity College Dublin, and is interested in the decolonization movement in museums and increasing and improving public access to local history. Joan is an aspiring archivist and studied American history at Smith before earning her Master’s in Medieval Studies from the University of York (UK). She is equally interested in American social history and ancient languages. Despite their varied interests, both continue to find their way back to Cambridge to explore its history, and are excited for this opportunity to create a resource that will hopefully augment Cantabrigians’ understanding of their own city.

-

The term Cantabrigian refers to a resident of Cambridge. ↩︎

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.