The Small Grants for Digital Publications program supports early career researchers and scholars through funding and technical assistance. Throughout 2024, we will publish the outputs from current grant recipients—read on to learn more about this year’s cohort of awardees!

We are currently accepting applications for the 2024-2025 grant program. Please reach out to Ian Spangler if you have any questions about the application.

Ilana Bean, “Within the Body and Beyond It”

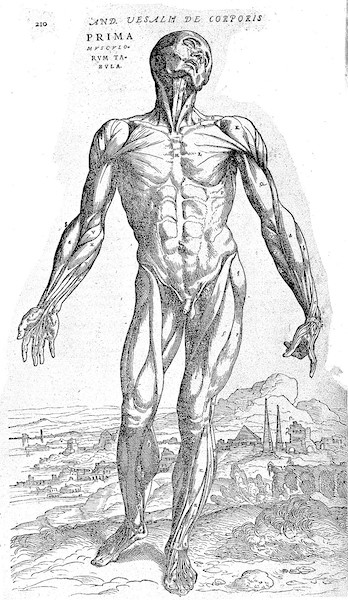

Vesalius’ famous “muscle man”, from Wikimedia Commons.

For the past few years, Ilana Bean has been working on an essay project considering anatomical atlases and the ways that space is mapped within the body. While researching Andreas Vesalius—an anatomist considered the father of European traditions of medical illustration—she learned that he had been university friends with Gemma Frisius, a Dutch cartographer who helped develop the famous Mercator projection. She began considering the influence each might have had on the other, and how geographic mapmaking could help her understand anatomical drawing.

Ilana’s project examines geographic objects from the Leventhal Center (and other map collections) alongside anatomical images, comparing their shared histories and production techniques. Geographical techniques like the Mercator projection and medical imgaes like Vesalius’s seminal anatomical atlas, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem, both represent space in complex, interrelated ways. In her essay, Ilana explores how these two specific works—the Mercator projection and the Fabrica—relate to each other. They were both developed by Flemish scholars and were released only twenty-three years apart, but the connection goes deeper: both works had long lasting effects on the how space is perceived, both within the body and beyond it.

Ilana Bean is an essayist currently based in Melbourne, Australia. Her research explores how medical imagery informs cultural understanding of the body. She received her MFA from the University of Iowa in 2023, where she studied Nonfiction Writing.

Allison Fulton, “Women’s Geological Mapmaking in the Early American Republic”

In this project, Allison Fulton places women’s craft-making and knowledge at the center of geological mapmaking in the early American Republic. At school and at home, girls and women refined their drawing and watercolor techniques by sketching and coloring maps and expanded their geographical knowledge by embroidering map samplers. Young women also often used these feminized craft skills in service of geological illustration, a rapidly developing arena in the early nineteenth century as geologists began to chart the natural resource composition of nations and conceptualize deep time. To bring the earth’s internal mysteries to light in a manner that served colonial and imperial interests, geologists needed skilled hands well-practiced in sketching, painting, and sewing; that is, the hands of women and girls.

A geological map of the United States by Edward Hitchcock.

Allison shows how cultures of craft-making and gendered domestic art techniques drove nationalistic fervor and rendered land and natural resources accessible for national consumption. She focuses in particular on the prolific geological illustrator and map maker Orra White Hitchcock, who collaborated closely with her husband, Amherst College geology professor Edward Hitchcock. As Edward conducted a geological survey of Massachusetts in the early 1830s, Orra set to work painting large geological textile charts, making black-and-white woodcuts of stratigraphic cross-sections, and hand tinting her Connecticut Valley lithographs and the large, foldout map of Massachusetts that depicted the state’s geological features. The official report published in 1833 by the state government was the second of its kind in the U.S., and the large-scale, boldly colored geological map was an early precedent to the dozen-plus state surveys conducted over the next decade. Orra’s work is exemplary of these practices in the period, and this research takes up the similar craft work of Eliza Tileston, Abigail Dunbar, and Mary E. Johonnot, whose manuscript maps of Massachusetts are housed at the Leventhal Center.

Allison Fulton is a Ph.D. Candidate in English with a designated emphasis in Science and Technology Studies at the University of California, Davis. She is at work on a dissertation on how nineteenth-century gendered craft traditions and technologies shaped the emergence of the modern American scientific establishment. Allison is the Albert M. Greenfield Dissertation Fellow 2023-2024 at the Library Company of Philadelphia and a 2024 Stacy Lloyd Fellow for Bibliographic Study at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation. Her work has also been supported by the American Antiquarian Society, Winterthur Museum, and Historic Deerfield, among others.

Alice King, “Visions of Control in Pequot Country”

The Pequot Country, a region in New England between the Thames and Pawcatuck Rivers, was the site of extensive competition during the seventeenth century. In May 1637, the General Court of Connecticut declared an “offensive war” against the Indigenous Pequot Nation in an attempt to seize control of their territory, culminating in an unprecedented massacre that trapped and killed at least four hundred Pequot men, women, and children at their palisaded fort on the Mystic River. Throughout the seventeenth century, English colonists and Native communities took up arms, signed treaties, seized captives, forged alliances, and raided villages all to try and take control of this region. In this project, Alice King illuminates the people, resources, and visions that shaped the Pequot Country during the colonial period, using a selection of maps from the Leventhal Center’s collections.

John Seller’s 1675 map of New England, from LMEC collections.

By interpreting and analyzing maps from the period—and putting them into conversations with key drivers of regional conflicts, such as wampum, corn, and animal tributes—Alice explains how different groups ascribed different values to Pequot Country. The Pequot refugees who survived the war wanted to regain their homelands and one of their leaders, Robin Cassacinamon, launched a campaign of petitions and tribute payments to try and win over influential English allies. Many English colonists wanted ownership of the land itself, but some leaders decided that making the Pequot survivors their tributaries was a more strategic move because they had valuable connections, resources, and knowledge that could be used to sustain the fledgling colony of Connecticut. Alice’s analysis draws on maps featured in Becoming Boston, including John Seller’s “A mapp of New England” (1675) and a 1662 map of Pequot Country drawn by local Indigenous leders.

Alice King is a PhD Candidate in the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia. She is working on a dissertation about the defining influence of Indigenous tribute practices on the colonial state in Connecticut during the seventeenth century. Alice is a Jefferson Scholars Foundation Fellow 2023-2024 and her work has been supported by the Folger Institute, Mystic Seaport Museum, and the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, among others.

Charlotte Leib, “Lively Landscapes and the New Jersey Meadowlands”

When European settlers came to the Americas in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, they occasionally marked on maps how much hay they believed a coastal meadow might produce. These settlers’ speculative assessments of hay yield, and their tenuous attempts to wrest more meadowland from Native American control for the purposes of feeding their horses, oxen, and cattle set in motion patterns of energetic exchange, capital accumulation and meadow dispossession that shaped the subsequent development of regions from Boston, Massachusetts to Washington, D.C. Coastal meadows, as Charlotte Leib argues in her dissertation, quite literally helped to build the city-region within which the Leventhal Center sits. Yet, as her article will show, maps only tell part of the story of how this happened.

Excerpt from a ~1767 map showing the west shore of the North or Hudson River, from the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division.

In her article, Charlotte will detail how digital tools and diverse archival sources, like herbaria specimens, census data, and paintings, can be analysed alongside maps to offer new insights into how human attitudes towards particular plants and entire landscapes have shifted across consecutive energy regimes, from the pre-industrial organic to fossil fuel-centric economies. As part of her ongoing work, supported by LMEC, Charlotte is also gathering maps from various library collections along the east coast, including the Leventhal Center’s collections, to create a general representation of settlement patterns along the Northeastern Atlantic coast during the colonial and Revolutionary periods.

Charlotte is an environmental historian and educator with twelve years of combined experience in the fields of landscape architecture, history, design, and education. She is currently completing a PhD in History at Yale University, where she has served as a Teaching Fellow for courses on urban history, environmental history, architectural history, energy history, and the history of science & technology. Prior to her doctoral studies, Charlotte received a BA in Architecture from Princeton University and dual Masters degrees in Landscape Architecture and Design Studies, with distinction, from Harvard University. Her work is currently supported by Fellowships from the American Philosophical Society, the John Carter Brown Library, the State of New Jersey Historical Commission, and the Boston Public Library Leventhal Map & Education Center.

Savita Maharaj, “Afro-Asian Diaspora and the Eaton Sisters”

The Eaton sisters (Edith, Grace, Sara, and Winnifred) were born in the late nineteenth century, and because of their mixed identities as being both Chinese and Europeans, they faced structural racial and gender marginalization that led them to contest social injustices and racism in their writings. The Eaton sisters are foundational figures in the realm of Asian American Studies today. However, their diasporic travel, publishing works, and textual networks in the Caribbean (particularly Jamaica) have not been given much focus. Questions abound regarding their stories: for example, why did the Eaton sisters write under pseudonyms in Jamaica? Was there a connection between the Black and Chinese communities in Jamaica during the late eighteenth to nineteenth centuries, and to what degree have such communities persisted today?

The poster for a 1903 production of Winnifred Eaton’s A Japanese Nightingale, from Wikimedia Commons.

In this project, Savita Maharaj documents the places and spaces where the Eaton sisters—particularly Edith and Winnifred—lived and wrote, including Jamaica, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, Boston, Richmond, Cincinnati, Chicago, New York, Nevada, Alberta, Calgary, and Hollywood. For example, Winnefred Eaton’s published Busybody and Man on the Street while working for the Gall’s News Letter during a trip to Kingston, Jamaica from 1895 to 1896. Savita explores the geographies of these archival texts, drawing attention to Afro-Asian identities, networks, and their place in Caribbean Studies.

Savita Maharaj is an English PhD student at Brandeis University. She received her Bachelor of Arts in English from Northeastern University in 2022. Her research interests are contemporary and eighteenth-century Caribbean history and literature, archival theory, critical histories of race and gender, and postcolonial theory. Savita currently serves as project manager and curriculum creator for the Early Black Boston Almanac.

Our articles are always free

You’ll never hit a paywall or be asked to subscribe to read our free articles. No matter who you are, our articles are free to read—in class, at home, on the train, or wherever you like. In fact, you can even reuse them under a Creative Commons CC BY-ND 2.0 license.